N̓syilxčn̓ language teacher Sofia Terbasket-Funmaker, Sylix, Anishinaabe, Ho-chunk. Photo: Kelsie Kilawna/IndigiNews

All that we know and all of our relationships grows from the words of our ancestors — that is the guiding principle at First People’s Cultural Council’s (FPCC) Indigenous language programs.

Sofia Terbasket-Funmaker is one of the many language learners dedicated to breathing life into her language, and passing it on to future generations.

Funmaker is a N̓syilxčn̓ language learner and teacher whose roots are Sylix, Anishinaabe, and Ho-chunk. She’s dedicating her time to language immersion and expanding curriculum resources. She uses standardized curriculum for classes at the Sylix Language House, and is designing her own project-based methodologies on the side.

She spent last summer working as a language nest assistant working with a small group of children aged two to five.

“Every day we would go somewhere new, usually to a park outside and we’d do different curricula, different activities outside, all in the language,” says Funmaker.

Funmaker recently completed a full year of immersion with the Sylix Language House. After three months, she had learned enough to start working as a language teacher, while continuing as a language student, she says.

This month, Funmaker was approved for a grant called YES (Youth Empowered Speakers) through the FPCC, enabling her to work with a fluent elder 10 hours a week for the next year.

The project at the Sylix Language House is one of many funded by FPCC this year. The provincial organization funded 600 language-related projects from April 2020 until March 2021.

The seeds planted through FPCC funding and Indigenous language programs are blossoming into a variety of programs, with cross-pollinating to create strong community connections.

Aliana Parker, FPCC language program manager, spoke of the long-term vision of the organization, which has been funding cultural programs for more than 30 years.

“The vision is that all First Nations languages in B.C. have stable populations of speakers who are passing their languages on to the next generations,” Parker says.

According to the most recent FPCC Status of languages report, there are 34 Indigenous languages, and more than 90 dialects in B.C. — all considered endangered. In 2018 there were a reported 4,132 speakers total, or 3.0 per cent of Indigenous people in B.C. Data is gathered every four years so the next report will be in 2022.

With 60 per cent of Indigenous languages in Canada in the area known as B.C, this is one of the most linguistically diverse regions of the world.

“Every First Nations language in B.C. faces extinction within the next ten years unless more is done to support them,” says First People’s Language Map of B.C.

The report also states that the number of language learners is increasing 10.2 per cent of Indigenous people in B.C were learning languages as reported in 2018.

While the pandemic has impacted all the funded Indigenous language programs, involving mentorship partnerships, non-profits, nations and more, Parker says projects have been able to shift and adapt to continue their work.

“People who work in language revitalization are really creative innovators and it was exciting to see that communities were able to shift plans and carry on with projects in a safe way using online tools,” she says. “In fact, many who had never used technology before learned how, and I think today most enjoy using new technologies to connect and carry out their work.”

One recipient is Pacific Association of First Nations Women (PAFNW), inclusively serving Indigenous communities, including urban and off-reserve. PAFNW envisions a matriarchal community where all Indigenous women in B.C. are safe and respected with a sense of belonging and connection to cultural traditions, as stated in their mandate.

FPCC has funded the hiring and support of fluent Nehiyawewin (Cree) and Anishinaabemowin (Ojibwe) language teachers. People learning the language are Indigenous people living in Vancouver away from their home territories, says language program manager Eden Fine Day.

Fine Day is a Plains Cree artist from the Sweetgrass First Nation in Saskatchewan, raised mostly in B.C.

The pandemic shifted Indigenous language programs that have existed since 2018 online, allowing for a wider outreach, she says, and registration has skyrocketed.

Fine Day says the language lessons have wellness benefits for the teachers as well as learners.

“It’s a way for them to see how valuable they are to us,” says Fine Day. “I treasure their knowledge and I treasure their experiences. And I’m so grateful.”

Elder Dorothy Sinclair Eastman is an Ojibway language teacher for PAFNW. She is from Little Saskatchewan Reserve, Manitoba.

“I was very close to my oldest brother James to whom I owe my deepest gratitude for teaching me every word I know of the (Saulteaux) dialect of the Ojibway language,” she says.

Eastman is pleased to see a growing movement of reclamation of culture, and preserving knowledge. Learning from Elders is important, she says, and this can’t fully happen without the language.

“Without the language, there is still a part missing,” says Eastman.

People are attracted to learning their languages, because it helps them heal some of those missing parts, says Eastman. She has seen the change when people start to learn.

“They said, ‘Oh, this is like coming home’. It was really touching,” says Eastman.

“The most important thing is keeping it going, and the language and the culture, not only our people, but beyond. So the mainstream society will understand us more. That’s the most important part.”

Eastman says the language classes strive to create community and connections. One young student in the class, Cicada, uses language as a way to stay connected to her grandmother. She phones her grandmother every week, to listen to stories, and chat about life.

Intergenerational connection and wellness go hand in hand, says her father Danilo Caron, of Sagamok First Nation.

Language teacher Evelyn Voyageur agrees.

She teaches Kwak̓wala at North Island College (NIC), and is from the Musgamagw Dzawada’enuxw Nations.

She says language cultivates deeper connections between generations.

“I believe it’s because the kids can sit and talk to the elders and they understand what the elders are saying. And that’s how they’re connected,” she says.

From that connection, comes guidance and healthy paths, says Voyageur. She’s seen the benefits from watching her own grandchildren and great grandchildren maintain strong connections to culture and language.

“Language relates to wellness because they now have role and positive role models. The younger generation sees how the older generation are doing things- and they understand what the older people are doing and saying,” she says.

Her granddaughter Carla Maxmuwidzumga Voyageur also teaches Kwak̓wala at NIC. Carla is also from the Musgamagw Dzawada’enuxw Nations, with Nisga’a roots.

She received funding from FPCC to digitize and translate a collection of language cards. Her great grandfather, Billy Sunday Willie had the foresight to document the language cards. Carla says linguist David Mcclintock Grubb recorded him speaking the language in the 1970s.

“I think people don’t understand how much work goes into language revitalization,” she says. “A few words can be a couple of hours worth of work, cleaning up audio and transcribing and trying to understand where the root of the word came from.”

Carla speaks of the tools and values that are embedded in words — how the words are connected to places and people.

“There’s always surprising moments with language where you get little goldmines of information or it leads your speaker to remember something or just offer information about something else, you know, that’s kind of distantly related or completely related,” she says.

“Learning your Indigenous language is really both coming back to yourself and to your people and learning how to live in this complicated, modern world that we live in.”

Scanning, transcribing, and working with her grandmother on translating words was a year of work that will continue, as she says her personal commitment to the project extends far beyond the funding period.

Funmaker can relate and says teaching the language herself has allowed her to try different approaches and allow students to focus on what interests them.

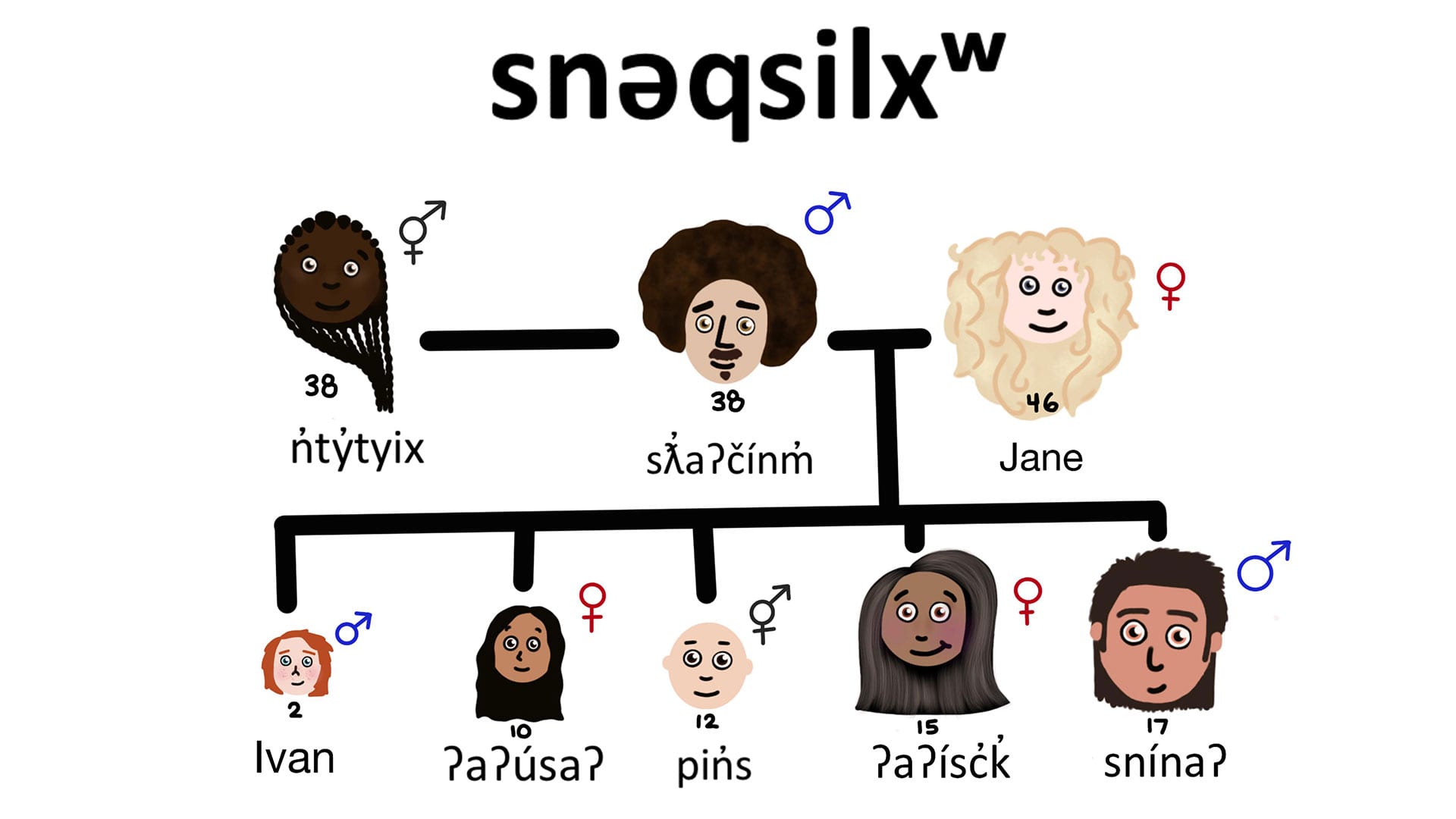

She has now created conversation groups for practicing, on a volunteer basis. She wanted to try her own project-based language classes to explore different ways of teaching. For example, in her curriculum, a student did a family tree project in which Funmaker added a third term for non-binary or Two-Spirit individuals.

“Which is really important as well in the language to make space for that,” says Funmaker.

Project-based language learning resulted in one student creating teaching resources, such as this inclusive family tree. Graphic by Tara Styan

“We need to start centering women and Indigenous or Indigiqueer folks in everything that we do. Also my sibling is non-binary. So it’s important for me to make space for non-binary indigenous folks, everywhere, especially in the language,” Funmaker says.

There are special moments in reclamation and identity through learning the language, says Funmaker.

“Just today, I learned my late grandfather was a fluent N̓syilxčn̓ speaker. Elder Wilfred “Grouse” Barnes came in to speak with our advanced class. He knew my mom’s dad, they played baseball together and spoke the language.”

“It’s this really deep, profound journey to myself, learning the language. This is a journey of many emotions,” says Funmaker.

“It’s a connection back to my identity and it’s a connection to my grandpa, to my ancestors — I really feel them holding me up as I’m speaking.”