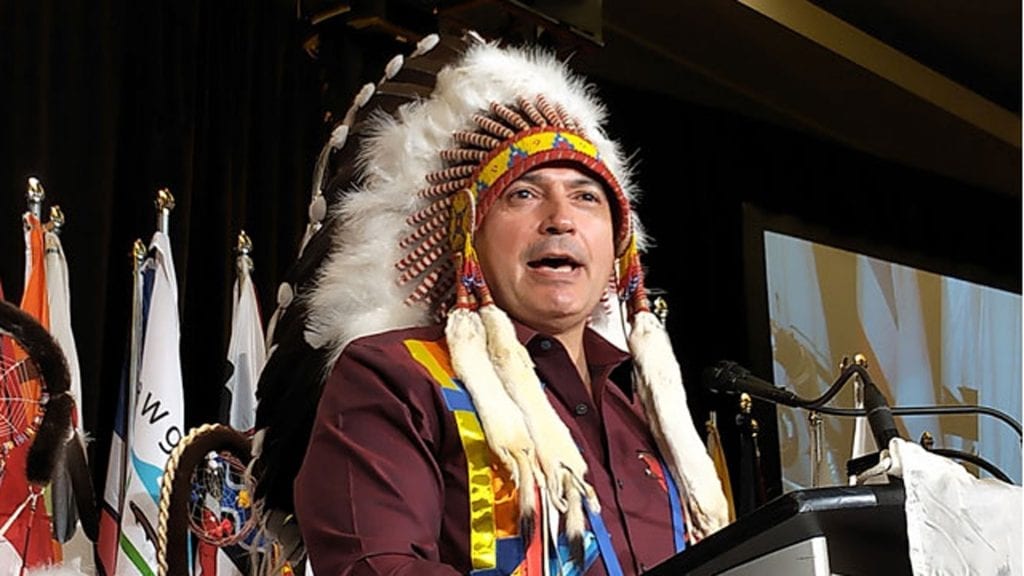

'This legislation ensures that First Nations laws are paramount,' said AFN National Chief in an opening statement to the virtual event. Photo: APTN.

Leaders from across Canada recently gathered to talk about Indigenous child and family wellbeing, and the implementation of the Act respecting First Nations, Inuit and Métis children, youth and families, also known as Bill C-92.

“This legislation ensures that First Nations laws are paramount, so we can focus on prevention, as opposed to apprehension,” says Perry Bellegarde, National Chief of the Assembly of First Nations (AFN), in a welcome letter to those participating in the virtual gathering on Jan. 19.

Since the Act came into force, “there has been significant effort by First Nations across Canada to take back authority for child and family services,” says University of British Columbia law professor Mary Ellen Turpel-Lafond, who broke down the Act’s key principles in her keynote presentation.

This was the first of five virtual leadership gatherings focused on the Act — which came into force on Jan. 1, 2020 — to be hosted by the AFN.

Over the course of the series, attendees can expect to “hear presentations and updates about the Act and its implementation, learn about tools and resources for First Nations leadership implementing the Act, and discuss the changes that will come with implementation,” says Bellegarde.

‘We are in a moment of change’

The Act was co-developed with Indigenous peoples, provinces and territories to reduce the overrepresentation of Indigenous children and youth in care, according to the Government of Canada.

“We are in a moment of change,” says Turpel-Lafond, who served as B.C.’s Representative for Children and Youth from 2006-2016.

Under the Act, there are two options for Nations to exercise their jurisdiction over child and family services, according to the Government of Canada.

Nations can give notice of their intent to exercise their jurisdiction to the Minister of Indigenous Services and relevant provincial or territorial governments. In this case, the Indigenous governing body’s laws on child and family services would “not prevail over federal, provincial and territorial laws.”

Read More:

Federal Indigenous child welfare Bill C-92 kicks in – now what?

Or Nations can request a “tripartite coordination agreement with Indigenous Services Canada and relevant provincial or territorial governments.”

In the latter case, if parties can reach an agreement within 12 months “or reasonable efforts to reach an agreement were made” during that year — “including use of alternative dispute resolution mechanism” — the Indigenous governing body would exercise its jurisdiction and its laws on child and family services would “prevail over federal, provincial and territorial laws.”

As of Dec. 23, 2020, Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) had “received requests and notices to exercise jurisdiction under the Act from 26 Indigenous governing bodies, representing 64 Indigenous groups and communities,” according to an ISC spokesperson.

Nine Nations have sent notice of their intent to exercise their jurisdiction while 17 Nations have requested coordination agreements.

Reframing ‘the best interests of the child’

Not only does the Act create pathways to self-determination for nations working to reclaim jurisdiction over child and family services, but Turpel Lafond says it also “reframes’’ the best interests of the child — a key concept in Canada’s child welfare system.

“There’s a concept or doctrine in the provincial child welfare system to remove the kids, and to say it’s not in the best interest of First Nations kids to be with their families.”

Under the new legislation, the best interests of the child are reframed to include the principles of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People, she says.

“We know [that UNDRIP] has very important protections and provisions,” she says, pointing to Article 8 of the declaration, which calls on the state to “provide effective mechanisms” to prevent “any form of forced assimilation.”

“The best interest is no longer about the removal,” says Turpel-Lafond. ”The best interest is about keeping children with community.”

The next virtual gathering in AFN’s series will be on Feb. 9, with a continued focus on navigating Indigenous child and family services legislation. Anyone can register to attend and there is no cost.