A Crown corporation at the centre of sexual abuse allegations against Indigenous women in northern Manitoba did not begin to formally record incidents of abuse, harassment or discrimination by its project workers until a little over five years ago, APTN News has learned.

Serious allegations were raised last summer against Manitoba Hydro by an arms-length agency of the Manitoba government but the corporation did not systematically monitor negative worker interactions until as late as 2012, according to documents accessed through the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (FIPPA).

Recently, nine cases of sexual assault at Hydro’s Keeyask generating station were investigated by RCMP, leading to four men being charged with sexual assault.

All of this comes after a 165-page report was released by the Manitoba Clean Environment Commission, reporting that Hydro workers allegedly sexually assaulted nearby Fox Lake community members in the 1960s.

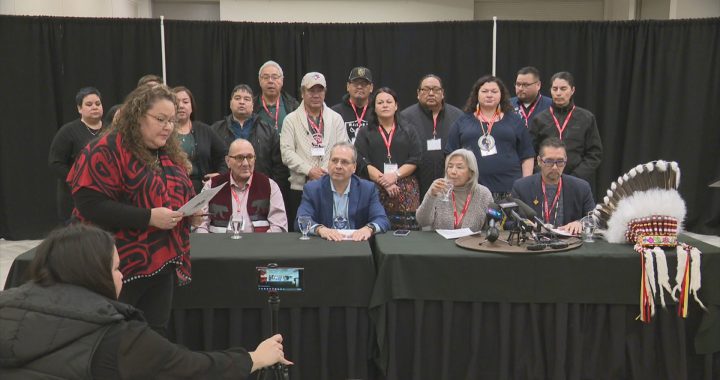

(MKO Grand Chief Garrison Settee at a rally in Winnipeg. Photo: Martha Troian/APTN)

“It is shocking that [Hydro] only started taking records in 2012. And the history of these projects go back 50 years. Why did it take so long to begin recording incidents?” said Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakanak (MKO) Grand Chief Garrison Settee.

“It is shocking to know that they only started recording that.”

MKO is the political organization that represents northern Manitoba First Nations. Four of those communities partnered with Keeyask Hydropower, a hydroelectric generating station on the lower Nelson River.

“I seen women raped” — Report alleges hydro development led to abuse in Manitoba

People march on Manitoba legislature demanding changes to how Manitoba Hydro does business

MKO is calling on the province to hold a public inquiry into the historical and current allegations of sexual violence, racism and discrimination at past and present hydroelectric projects in the north.

Sexual abuse and discrimination not “formally or systematically recorded”

Prior to 2012, Hydro did not formally or systematically record allegations of abuse, harassment, or discrimination by project workers.

“Hydro employees might have received, been aware of, or even acted upon an incident or allegation. It is clear that there was no standard operating procedure, instruction, or program related to these incidents. Any records created would have been in transitory and likely destroyed once a project was complete,” according to the FIPPA documents.

In addition, record management practices and legal requirements have changed dramatically since the 1980s.

Sandra D. Phillips from Manitoba Hydro Legal Services prepared the response.

(Manitoba Hydro building in Winnipeg. Photo: Jesse Andrushko/APTN)

APTN initially asked for a list of all senior management and board of directors from 1950 to 1980 who may have been involved in any or all complaints to do with any of the allegations.

It was told publication of any individuals employed as managers with connection to any historical allegations of abuse could inappropriately and unfairly damage their reputations and expose them to public condemnation, ridicule and harm. It could also threaten or harm their mental health, well-being and physical safety.

“Hydro does not have a readily available record identifying all of the individuals employed as department or division managers, or the equivalent predecessor roles or titles [for the time period],” Phillips wrote.

Power Failure: The impacts of hydro dams in Northern Manitoba

$21,000 retrieval fees for documents

Manitoba Hydro also informed APTN it has more than 2,400 boxes of paper records pertaining to the construction of generating stations in northern Manitoba, which are kept in an off-site storage facility. Since none of those documents have any specific reference to complaints of abuse, discrimination, or harassment in their index, a manual search would be required.

Phillips estimated the cost of going through those documents would be $21,000, adding conducting such a search would unreasonably interfere with its operations.

“It’s sad. Not everyone can come up with $21,000 to pursue that information,” said Settee.

“For anyone to access this information, it should be free.”

Manitoba Hydro president designated head under FIPPA

APTN filed several FIPPA requests related to this matter. One of them asked who was behind the decision-making process to not fully comply with its request.

(Kelvin Shepherd, President and CEO of Manitoba Hydro)

In its response, Phillips wrote that under FIPPA, the ”head” of a public body is responsible for the administration of the act, including the processing of requests and decisions to grant or refuse access.

In the case of Hydro, its president is the designated head under FIPPA.

“Every access decision of Manitoba Hydro is reviewed and approved by the president prior to release,” Phillips wrote.

Dean Beeby, a journalist and expert in freedom-of-information laws, is not surprised by the lawyer’s response, given a minister or president may be responsible for the operations of the access to information act.

Still, he questions its practicality.

“Those decisions are never run by the minister. The minister just turns over the entire file to the authorized delegated person to make those decisions,” said Beeby.

“And that’s not how it works in practice. Nobody heading up a major organization would have enough time and concentration to deal with that kind of freedom of information issue.”

(Nathan Neckoway says there are many cases of abuse of men and women. Photo courtesy Nathan Neckoway)

Nathan Neckoway, a councillor with Tataskweyak First Nation, which is one of the partners with Keeyask Hydropower, said it is not over when it comes to addressing all of these allegations and First Nations members concerns.

“There are so many cases that occur, [and] not only with the women but with the guys. This discrimination, harassment and abuse happens at all levels, and to all members,” said Neckoway.

“Our voices are finally being heard and we’re in a position of trying to push it even more.”