Warning: This story contains details about residential schools that may be upsetting. The Hope for Wellness Hotline can be reached 24 hours a day at 1-855-242-3310 or online at www.hopeforwellness.ca

When Del Riley was five years old, Mounties showed up at his house on Chippewas of the Thames near London, Ont.

They wanted to haul him and his siblings off to residential school.

“We had eight kids,” Riley says on Nation to Nation. “My father had spent time in residential school. He was one of my grandfather’s 11 kids.”

Ten of those kids spent time in Shingwauk Indian Residential School in Sault Ste. Marie, and so Riley’s grandfather tried to fight the Mounties off.

“But it didn’t happen,” Riley says. “They ended up taking five of the eight.”

The year was 1950. Mount Elgin, the residential school on his home community, closed four years earlier. Riley was taken to the Mohawk Institute on Six Nations Territory in Brantford. Both he and his sister had tuberculosis.

“I was probably a biological weapon they were using,” he says. “They knew I had TB, because both my sister and I were in a sanitorium before that where my mother had passed away, and we came out as carriers.

“Then they put us in residential school. Her admission slip says she has TB. This was the most contagious disease at the time. There was no cure for it.”

Situated about 100 km apart, the Mohawk Institute and Mount Elgin were Canada’s oldest residential schools. Both opened prior to Canadian confederation — the only two operating at the time — and now both will be searched for unmarked graves.

Chippewas of Thames announced on the first National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, that a probe of the former Mount Elgin grounds is in the early stages and could take three to five years.

“While little remains of the imposing structures of the Institute’s buildings,” the First Nation said, “its role in Canada’s program of colonial violence and genocide haunts our family memories and lingers in today’s generations in ways that we have yet to fully identify.”

Meanwhile, back in July, Six Nations police said they would launch a probe into child deaths and unmarked graves at the former Mohawk Institute.

Kids from about two dozen First Nations were forced to attend both schools. Both were known as the “mush hole” due to the bad food. Both were run not by the Vatican, but rather the Protestant Church.

Mount Elgin was founded in 1847 by Methodist preachers and was operated by the United Church after 1925. It was the first school to receive government funding.

The Mohawk Institute was founded by the Anglican Church in 1831. Kids in both institutions were barred from speaking their language or practicing their cultures. Fires, truancy and abuse were common.

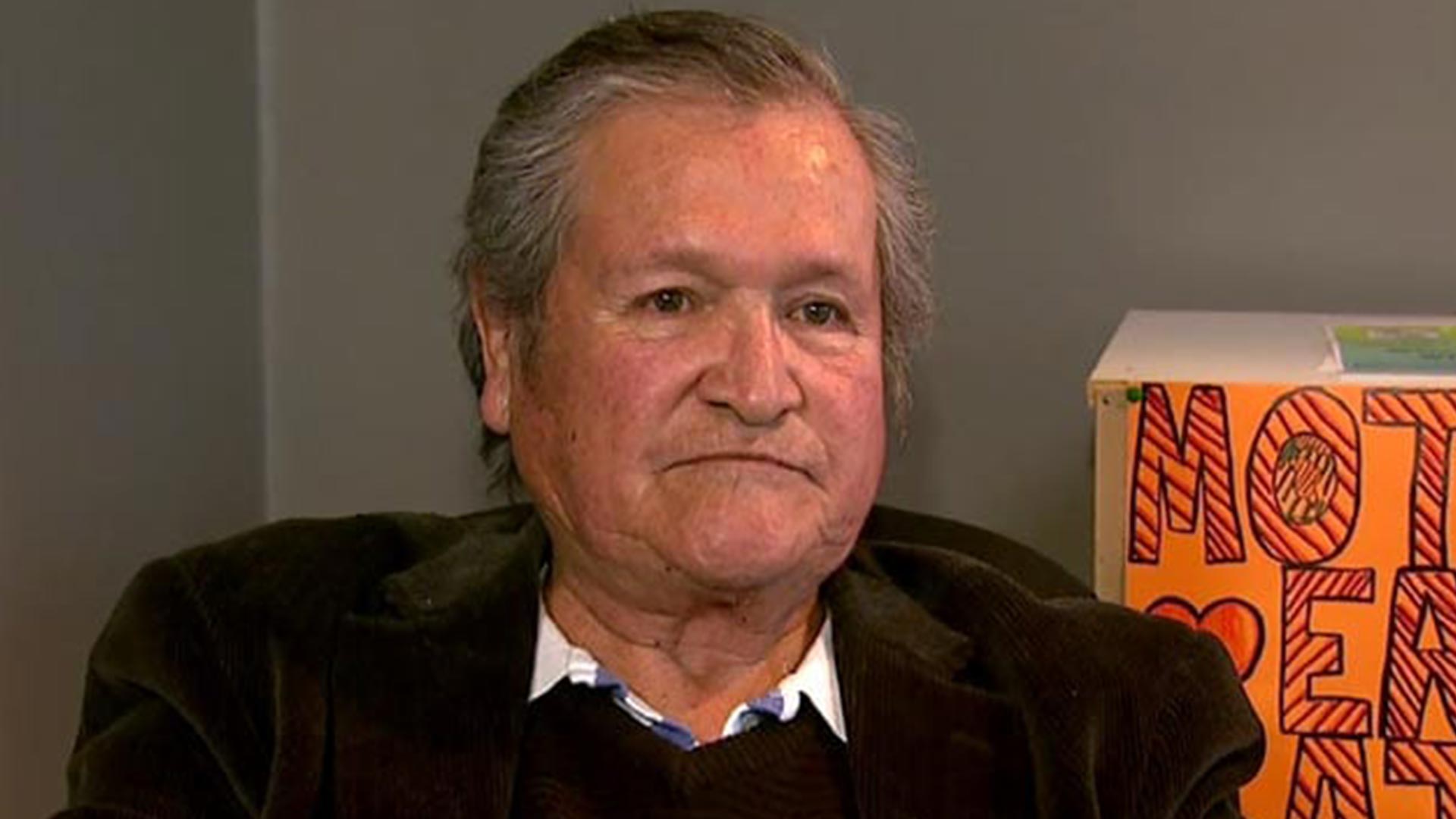

Riley survived five years in the Mohawk Institute and went on to have a prosperous career. He led the National Indian Brotherhood during the 1982 patriation of the Canadian Constitution. That same year, he turned the organization into the lobby group known today as the Assembly of First Nations.

Later in life, instead of opting into the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement, which was the largest class-action settlement in Canadian history at the time, he sued the Anglican Church on his own.

“Because they didn’t want to go into the actual courtroom, they settled with me,” Riley says. “But they never did give me an apology. And the conditions I went in with, it was probably the worst that anyone could ever imagine.”

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission documented about 50 deaths at the Mohawk Institute. At Mount Elgin, the commission documented only five.

The institutions had similar capacities, were roughly the same size and operated for about the same span of time. So why are those numbers so different, and what could the probes reveal?

Riley says much of the evidence may have been destroyed and lost to history, especially considering how long ago the schools were founded. But he points to the findings of whistleblower Dr. Peter Bryce as an indication of just how common death was in the early days of both schools.

Bryce found, after investigating tuberculosis conditions in 1909, that the death rate for kids in residential schools was 20 times higher than the national average.

“So if you extrapolate that 10 years before and 10 years after,” Riley says, “you’re going to see that the death toll was substantial.”

And he had more to say on the topic.

Watch the full interview above.