With concern about climate change increasingly on the front burner globally, nuclear power is getting renewed interest as a carbon-free energy source.

The federal government is looking to the potential of small modular reactors, or SMRs, as a way to power remote industrial locations and northern communities.

Canada has its SMR Action Plan – which sees the development of small modular nuclear reactors as being necessary to help get us to net-zero emissions by 2050.

And in 2020, then Natural Resources minister Seamus O’Regan set the tone for this nuclear revival when he gave the keynote address at the Canadian Nuclear Association’s annual conference.

“We are placing nuclear energy front and centre,” said O’Regan. “Of course – nowhere is the potential of nuclear greater than it is with respect to small modular reactors – to generate electricity, and power resource extraction in distant places …and to offer a clean alternative source of light and heat in rural and remote communities.”

One of the remote areas being considered for small modular reactors is Nunavut, where power comes from diesel generating stations.

Qulliq Energy Corporation – the power company owned by Nunavut – is listed along with Bruce Power, Ontario Power Generation, New Brunswick Power and SaskPower, as a utility participating in the SMR Action Plan.

Former Iqaluit mayor Madeleine Redfern signed a recent open letter advocating for nuclear power as part of the plan to mitigate climate change put out by Canadians for Nuclear Energy.

The Inuk politician is also on the board of the Ultra Safe Nuclear Corporation, which has a micro modular reactor in development at the Chalk River nuclear facility in Ontario.

This is just a small slice of the attempted nuclear revival underway – but all told, it’s big news for an industry that has been in decline.

So what does it mean for the main and major problem posed by nuclear energy – the waste – which can be dangerous for hundreds of thousands of years?

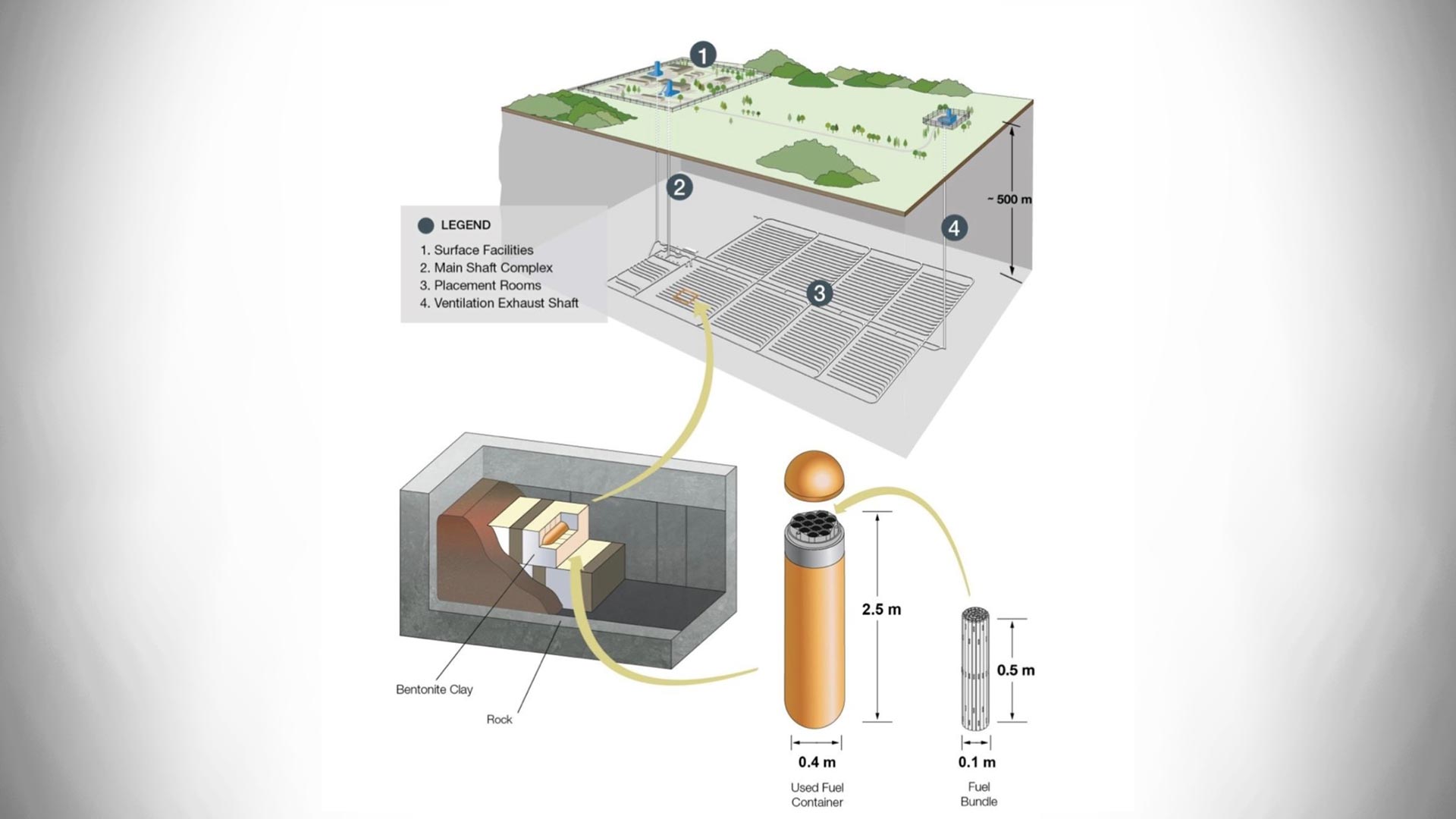

With that question in mind in Nuclear Revival, APTN Investigates updates reporting done in 2020 about “Canada’s Plan” – which is the name the Nuclear Waste Management Organization (NWMO) gives to their quest to find a place to bury 4.8 million bundles of used nuclear fuel.

More specifically, the NWMO, which is a consortium of Canadian nuclear industry players created by an act of parliament, is looking for a community willing to allow used nuclear fuel to be placed in what’s called a deep geological repository – or DGR.

Currently, the NWMO is engaging with Ignace, Ont., a small community 250 km northwest of Thunder Bay, as well as the municipality of South Bruce, on Lake Huron northwest of Toronto.

First Nations communities in the area of Ignace and South Bruce are being courted by the NWMO as well.

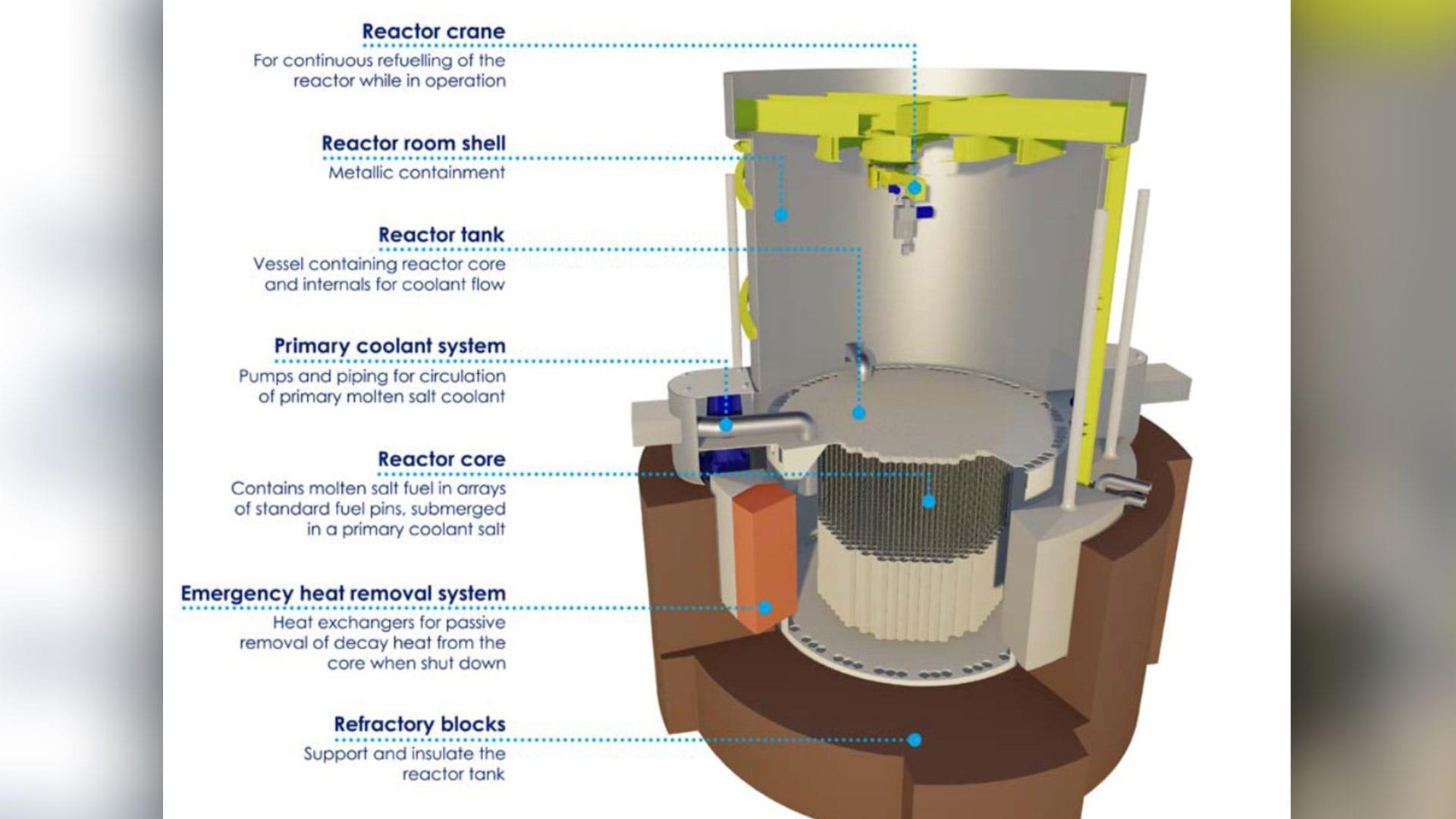

While the NWMO looks for a place to bury used nuclear fuel in Ontario, a company called Moltex in New Brunswick wants to reuse that same nuclear fuel in their first-of-a-kind small modular reactor design.

Moltex is one of 11 potential small modular reactor vendors listed on the SMR Action Plan website.

The company has been given $50.5 million by the federal government to develop its SMR at Point Lepreau in New Brunswick – which is on the north shore of the Bay of Fundy and in Peskotomuhkati (formerly known as Passamaquoddy) traditional territory.

“If we want to get to net-zero by 2050, it’s pretty clear that even though there’s a lot of challenges in nuclear, we need nuclear power to be part of the mix to supplement renewable power when the sun isn’t shining and the wind isn’t blowing,” says Rory O’Sullivan, CEO of Moltex Canada.

Moltex wants to use spent nuclear fuel from New Brunswick Power’s Point Lepreau Nuclear Generating Station in their SMR.

“Instead of putting it in the ground where it’ll be radioactive for very long periods, we can reuse it as fuel to create more clean energy from what was waste,” says O’Sullivan.

This, O’Sullivan argues, will help make the spent fuel safer.

“We can’t get rid of the waste altogether, but the aim is to get rid, to get it down to about a thousandth of the volume of the original long-lived radioactivity,” says O’Sullivan.

But Gordon Edwards, a prominent Canadian nuclear critic is not buying the safety case presented by Moltex.

Edwards is president of the Canadian Coalition for Nuclear Responsibility and works on a radioactive task force with the Anishinabek Nation and the Iroquois Caucus.

For one thing, Edwards is uneasy about the fact that Moltex would like its SMR to be used around the world, and countries with this technology might want to use plutonium acquired in the Moltex process to make nuclear bombs.

“By spreading this technology around the world, we’re giving many different countries the opportunity to access plutonium – to separate plutonium,” says Edwards, “and that means that we’re almost inviting people to take advantage of the opportunity to develop their own nuclear weapons program, as North Korea has done, for example.”

Moltex, on the other hand, says its process does not involve extracting plutonium per se.

“We are not extracting plutonium,” O’Sullivan told APTN. “Extracting plutonium would not be possible in Canada. Plutonium on its own is a very dangerous, hazardous material. But we are doing is taking out all of the long-lived radioactive waste as a result of the spent fuel, which is only about half a percent. So it includes the plutonium, but it’s all the other contaminants as well. We don’t go near plutonium separation.”

But Edwards is of the opinion that Moltex is going close enough to plutonium separation for it to be a problem.

“Moltex claims that because the plutonium is not being separated all by itself, because it’s also separating out these other heavier than uranium isotopes that therefore it shouldn’t be a problem for weapons because you need to get pure plutonium to really be able to make a good nuclear weapon,” says Edwards, “but they’ve already done most of the work.”

Like Edwards, Peskotomuhkati Nation, which counts the land occupied by the Point Lepreau nuclear facility as part of its traditional territory, has concerns about the Moltex project as well.

“Well, I don’t feel very good about it, to be honest,” says Peskotomuhkati Chief Hugh Akagi, “If you pay tax on anything in this country, you’ve just made a donation to Moltex. If you’re not concerned about $50 million being turned over to a corporation for a technology that does not exist – I hope you heard me correctly on that.”

In Nuclear Revival, APTN also speaks with the NWMO about what SMRs might mean for plans to entomb high-level nuclear waste deep underground.

Derek Wilson is vice president of Construction and Projects for the NWMO and he says there are still unanswered questions, including one about the potential use of enriched uranium in some SMRs on the drawing table.

“Until we have more information on the actual fuel type, the configuration of the fuel, and how that fuel would be received it’s difficult to say how the enrichment would impact our DGR,” says Wilson.

The issue with enriched uranium – which is not used in Canada’s CANDU-type nuclear reactors, is that it can go critical, or accidentally chain react.

“It’s called a criticality accident,” says Edwards, “releasing enormous amounts of energy just by the splitting of atoms spontaneously underground when the repository floods.”

Edwards believes that water will eventually find its way into the NWMO’s DGR over the eons it will be tasked with keeping nuclear waste safely separated from our environment.

Another issue facing NWMO as it considers what kinds of spent nuclear fuel might be coming out of SMRs is the geometry of these new fuel bundles.

That’s because the NWMO plans to put used nuclear fuel within a “multiple-barrier system” which has been designed to accept the standard size and shape of fuel bundles that are used in Canadian reactors.

Wilson says this is an issue being considered by the NWMO but adds that until we’re further down the road of SMR development it’s hard to know what the answers are.

“Can the vendor produce a fuel – a fuel waste that we would receive that could go into our container,” asks Wilson as he summarizes the problem. “So is there processing or can they configure their fuel in such a way that we could actually incorporate it into our used fuel container design? That’s probably the simplest.”

The question at the centre of all this is the safety of expanding nuclear energy production as a way to help us get net-zero emissions – and it’s a question some are hoping to hear from the new environment minister about.

The Ministry of Environment and Climate Change is listed as one of the federal entities supporting the SMR Action Plan, but Minister Steven Guilbeault is a former activist with Greenpeace, an organization that is against nuclear power and SMRs.

As recently as 2018 Guilbeault tweeted, “it’s time to close Pickering #Nuclear Plant and go for #renewables.”

Ontarians have better choice's, it's time to close Pickering #Nuclear Plant and go for #renewables via @oncleanair https://t.co/VQ1trkGUhN pic.twitter.com/QwTPlz3PKv

— Steven Guilbeault (@s_guilbeault) April 16, 2018

In an encounter at COP26, Guilbeault was questioned by Dr. Chris Keefer, president of Canadians for Nuclear Energy and an emergency medicine physician in Toronto.

Keefer asked Guilbeault to comment on the fact that the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [IPCC] is now presenting nuclear power in a positive light – but Guilbeault wouldn’t reveal his personal stance.

“What I’ve said publicly since I’ve been here – it won’t be up to the government to decide which technologies will flourish,” says Guilbeault in the exchange.

Guilbeault’s office did not respond to an interview request from APTN.

Neither did Jenica Atwin, Liberal MP for the Fredericton riding, who before crossing the floor from the Green Party earlier this year issued a statement calling Canada’s nuclear policies “profoundly misguided.”