Thousands of letters from Inuit tuberculosis patients evacuated in the 1950s and 60s obtained by APTN Investigates reveal government surveillance, loneliness and concern for families back home.

In 2017, APTN obtained 5,789 pages from the Library and Archives of Canada through the Access to Information and Privacy Act.

After inputting the data into a spreadsheet, APTN found more than 800 patient names were found from communities across the Arctic.

Their letters are featured in a two-part episode, Writing Home starting on May 15, 2020.

Letters were collected by the Department of Northern Affairs and National Resources until the mid ‘60s and most records in the collection are titled “Eskimo Correspondence Records.”

(Letters like Tommy Onalik’s were translated from Inuktitut to English using a standard form.)

Written in the original Inuktitut, the letters were translated into English by department staff.

Some were addressed to the government officials asking for news of family or specific requests in hospital but many were addressed to family back home and intercepted.

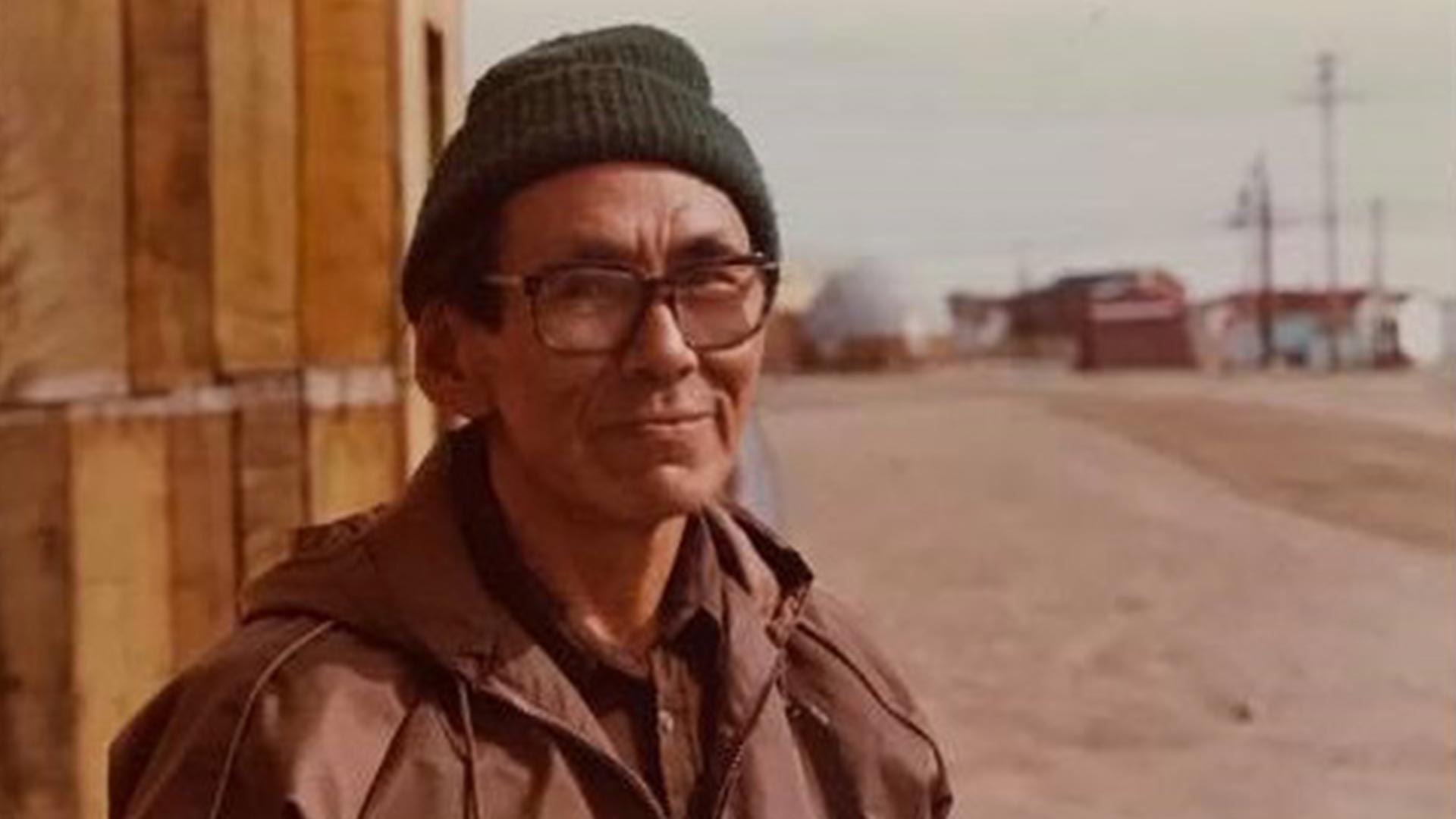

Annie Angoyuak’s father Tommy Onalik, like thousands of Inuit evacuated during the era, spent more than four years at the Hamilton Sanatorium.

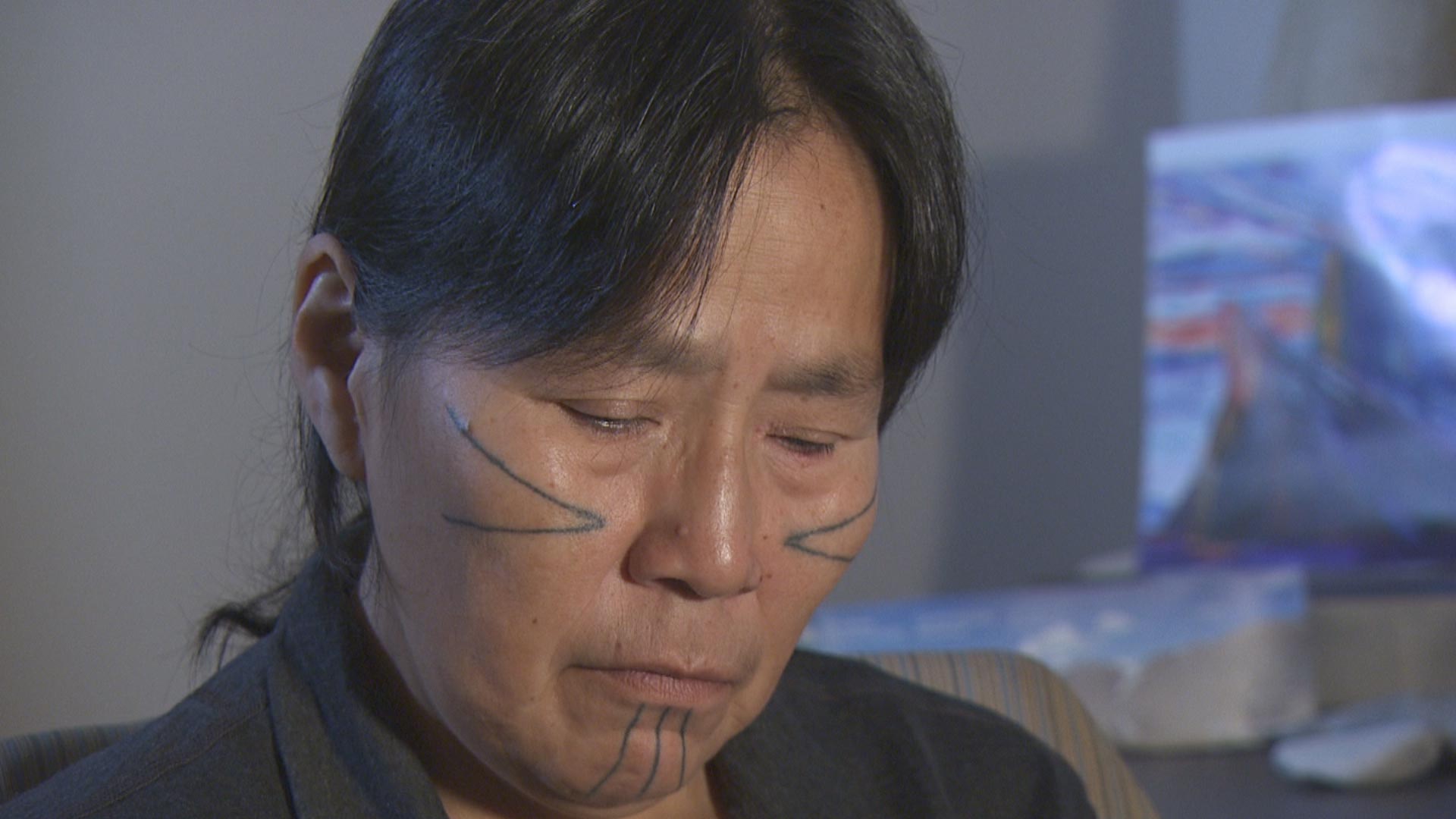

She said it is clear to her why her father’s letters were read and translated by department staff.

“It was censorship, I feel,” she said. “That is very sad for him. I feel sad and I feel angry.”

Onalik’s letters reveal increasing frustration at not being allowed to leave and intense concern for his family back home in Iqaluit, then called Frobisher Bay.

“My mother is blind and I pity her. My wife is alone. I’ve been away so long,” he wrote to a northern services officer. “All I can say is the white man’s land is enough to put you out of your mind. It is no good.”

Brock University History professor Maureen Lux has written extensively on Indian hospitals in Canada.

She says the fact the letters were translated fits into a larger context of surveillance of Indigenous people in Canada throughout history.

“Why they would translate personal letters is harder to justify,” she said. “I think it fits with the larger reserve system, for instance, in the south, where Indian agents very much knew everybody’s business.”

“These letters never made it home,” Angoyuak said. “Now to have read them and see them in his own handwriting, I feel for him.”

Angoyuak said the letters reveal a time in her father’s life that he refused to talk about like many Inuit Elders sent south for treatment.

“They didn’t want to remember this,” she said. “This is the same government we live under today.”

As part of the federal government’s 2019 apology for the treatment of Inuit during the era, a program called the Nanilavut Initiative was created. The goal of the program is to research and find grave sites of Inuit who did not return from treatment.

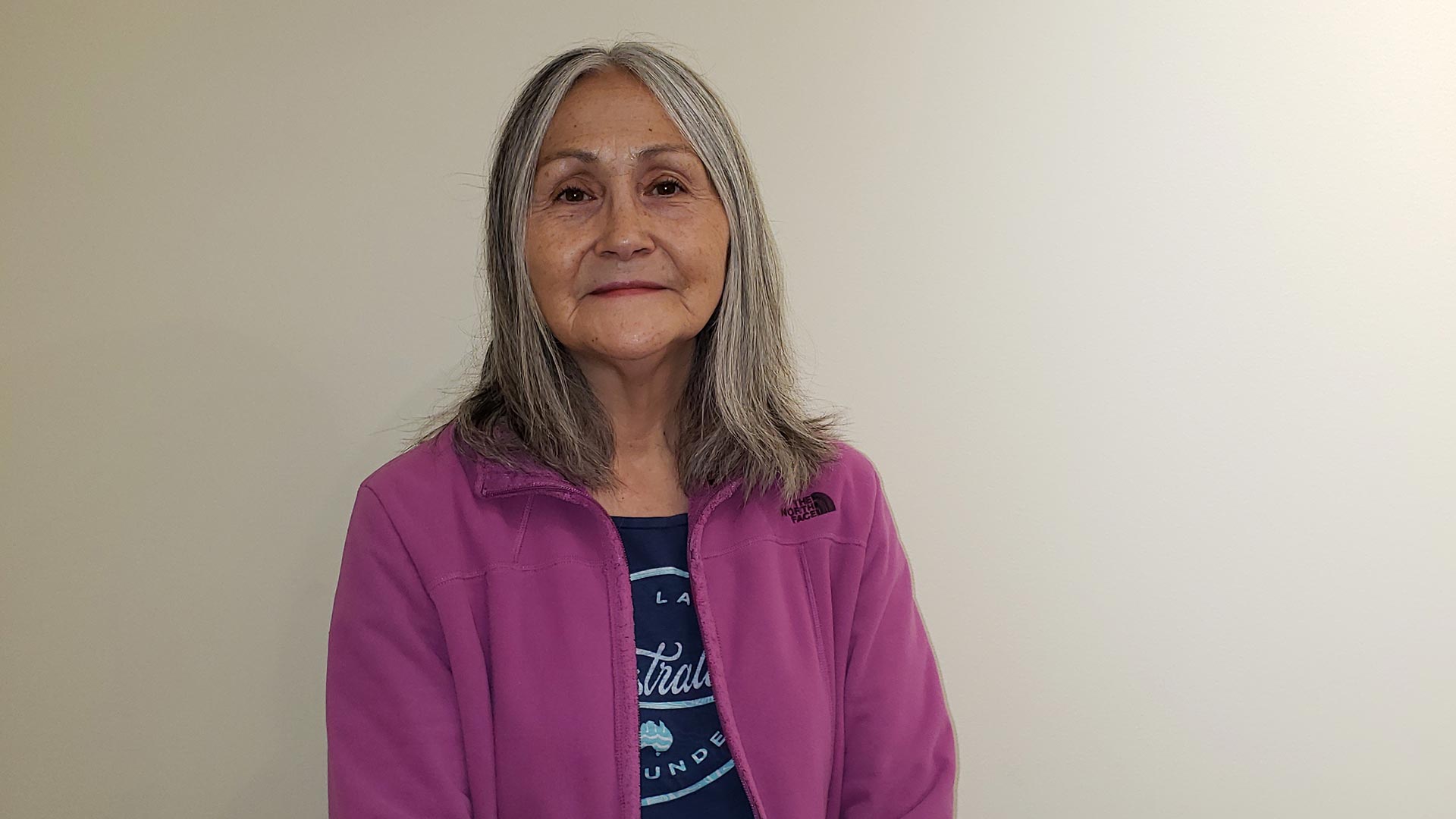

Beverly Lennie is a program administrator with the Nanilavut Initiative.

APTN shared the entire collection of letters and research with her to assist her family searches.

“It will be very helpful to families that may be searching for lost-lost loved ones,” she said. “They will help.”

She said it is important for the public to know that she cannot initiate contact with families because of privacy legislation.

“They have to contact me before I can get a search going,” she said.

Angouak said she is grateful that her father was one of the lucky ones who came home.

He went on to carve sculptures, set up camps and form strong relationships with his grandchildren before passing away peacefully in 1994.

“I think I’ve come full circle to understand the man that I grew up with. The trials he had gone through, the distrust he had of the hospital and the health system and the love he had for his family.”

If you would like us to search our letters database for yourself or a loved one, contact [email protected] or [email protected]. Contact Beverly Lennie at 867-777-7066 or send an email to [email protected] to assist in finding loved ones who did not return from tuberculosis sanatoriums in the south.