Dennis Ward

APTN Investigates

After she phoned her sister, Cpl. Esther Wolki took a knife and began cutting into her arm.

A decade with the Canadian Forces, including a tour in Afghanistan, the racism, sexual and emotional harassment had finally broke her.

“I started cutting very slowly, inch by inch,” said Wolki, in an interview with APTN National News. “And then I did both wrists. But still, I wasn’t feeling anything. So I cut into my veins.”

Forty minutes passed before someone found her and it was only because she forgot to lock the door of the room she was in at CFB Shilo.

She would spend the next three weeks at a psychiatric hospital in Brandon, Man.

It was Nov. 15, 2014.

On Thursday, Gen. Tom Lawson, the commanding officer of Canada’s armed forces acknowledged a problem with sexual misconduct in the military and he promised action. The military released a report from an internal review which found there was a “culture of misogyny” in the ranks.

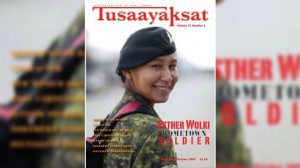

But for Wolki, it’s too late. She can’t wait for her military career to come to an end. An Inuk woman from a small community in the Northwest Territories, Wolki joined the military shortly after graduating from high school.

Now Wolki’s days at the CFB Shilo begin by counting out the handful of pills she needs to get her through the day. She needs them to keep her alive and prevent another suicide attempt.

“I’ve been scorned, scorned so hard from the military that I don’t think I deserve to live and I think suicide is the right for me to do because I think it’s the only peace I will get,” she said.

Her military career wasn’t supposed to be this way.

“It was pretty awesome at the start,” said Wolki.

Wolki’s story begins in the small Arctic community of Paulatuk which sits perched on the northern-most tip of the Northwest Territories. Here is where she spent her childhood, a happy-go-lucky time dreaming of seeing the world. That was part of the desire that drew her to the Canadian Forces, but there was also a practical motivation.

“I wanted to join so I could see different places and get out of Paulatuk, but mainly to make money for my family,” she said.

Wolki ended up at CFB Shilo, which sits about two hours west of Winnipeg. It is one of the largest military bases in Canada. It is also where Wolki experienced the darkest moments of her life.

“It started pretty much the first week I got there. There was other Native men there, Indians. And everybody presumed they were all my cousins and they’d ask me “You, this is your cousin, right? You guys are dating, right? Isn’t that would you guys do down in Northwest Territories,’” said Wolki.

She still remembers the words of one soldier.

“I was sitting there and he was like, ‘You know these people eat raw meat and piss in a bucket and wash their face with their piss because it’s warm,’” said Wolki. “He said, ‘Just quit and go back home and be a drunk like the rest of the Eskimos.’”

Wolki said the comments made her feel ashamed.

“They made me feel ashamed to be Inuit and from the North,” she said.

Some of the worst comments came from superior officers, said Wolki.

“You guys are the scum of Canada because you take welfare and you take up the government’s money. You don’t work for it. When you get your money, all you do is drink it up and you guys are drunks,” Wolki remembers one senior officer saying.

By the time she was packing her gear to deploy for Afghanistan, Wolki said she’d been labelled a drunken Eskimo and a dirty Indian.

Still, she soldiered on.

Wolki was stationed a forward operating base on the front lines in one of Afghanistan’s most violent regions.

“A lot of people got hurt and passed away while I was on tour. And it was really sad to see the soldier’s carried away in their caskets. And their buddies holding up the casket,” she said.

Like many other soldiers, Wolki returned from Afghanistan disturbed and depressed by what she witnessed.

“The nightmares I’d have were…I’d be in my combat clothes but in the house. And I’d be getting dragged down, downstairs into the basement by Taliban. And it was like that every other night,” she said. “I’d dream about being in Afghanistan and being shot up. And seeing my friends all lying down. Seeing my family members getting blown up. I remember trying to save some people and I was carrying a kid and there had been an explosion and everybody was dead. And I’d wake up screaming.”

Wolki said she feels her requests to be tested for post-traumatic stress disorder and other possible health problems were ignored.

Former veteran’s ombudsman Ret.-Col. Pat Stogran said many soldiers like Wolki are let down by the system.

“There are far too many cases of not only people in similar situations to this young lady but also people who have gone one step further out of despair and killed themselves,” said Stogran, who was 31 years in the military.

But things were about to get worse for Wolkie. She would face one of the darkest moments of her life in November 2014.

She was at a local watering hole n Brandon having casual drinks on a casual night when agreed to go to a house party in the city’s south-end with some male soldiers.

Things took a nefarious turn.

“There was one guy who was sober and I thought he was OK and I asked if he could watch over me. And he took me to the washroom and pushed me down on the bathroom and he pulled down his pants and he said just do it,” she said.

“And I was thinking it’s probably better than being raped because an hour before the guy I went to see, he was…I was kissing him in the washroom and he kept trying to turn me around and pull off my pants and I kept saying no.”

Wolki was desperate to get out of the situation.

The police report tells the rest. It said Wolki locked herself in the attic and shouted for help out the window, prompting neighbours to call 911. Neighbours said they heard a woman screaming saying she was being held against her will.

Brandon police initially took three males into custody that night, but later released them because the officers felt Wolki’s claims were “unfounded.”

Wolki says the Brandon police officers who dealt with the case treated everything like a joke, even warning her to stay out of attics.

Back at the base, her superiors weren’t laughing and they also had little interest in her side of the story.

One senior officer blamed her for embarrassing the soldiers.

“He’s like you got these soldiers in shit and you probably ruined their night and that’s all he was saying to me you made the regiment a disgrace, you’re a disgrace to the regiment. This was all… that’s what he was saying to me,” she said. “They thought that everything was my fault and that I ruined the guy’s lives and I ruined their night for them and likely ruined their job. That’s when they started yelling at me saying I was a disgrace to the military.”

She wasn’t offered an ounce of compassion.

“They didn’t even ask if I was OK or hurt, they just wanted me charged,” said Wolki.

A week later, she decided to kill herself in Shilo, the place that caused her so much anguish.

She placed one last call to her sister Celina in Paulatuk.

“I answered the phone and she sounded really different. She said I’m, I don’t want to leave anymore. I don’t want to deal with them anymore,” said Celina Wolki.

Then, the phone went dead and the sister panicked, she feared the worst was about to happen. And it almost did.

Back at the base, Esther Wolki grabbed a knife to cut.

Wolki still struggles to stay alive. The nightmares continue.

Stogran said the military has a serious problem dealing with mental health issues. He said the matter should not be treated as a political scandal because this is about real lives on the edge.

“Even if this young lady has the wrong perception of the way she was treated, the fact of the matter is that’s her reality. And it’s going to cause a huge problem in her life. And a problem, if the government doesn’t pick up the expense, is going to land in her family and in the community. These problems don’t go away,” he said.

Hope, however, glimmers on the horizon for Wolki. She expects her to be finally released from the military.

She is going home, back to Paulatuk, the only place where Wolki believes she can still find peace.

“I miss the landscape. I miss the people. A lot of kids look up to me. I’ll be able to make a lot of changes when I get back home,” she said.

@DennisWard

“I’ve been scorned, scorned so hard from the military that I don’t think I deserve to live and I think suicide is the right for me to do because I think it’s the only peace I will get,” she said.

Sad tragic, disgusting failure of the military to protect a soldier. Sounds a lot like American military bases..

I pray she finds peace in this life after such a horrifying ordeal..

Stay strong Esther. I remember well your visit to Repulse Bay, NU. You are a role model for Inuit youth and a wonderful person.

This is so sad to read…I do hope she recovers from the ill treatment she received from her “peers” in the military, & finds peace in her home town of Paulatuk NWT

God damn pigs. What a disgrace to our country. Disgusted disgusted disgusted. Would rather waste our tax dollars on providing our kids and seniors a better life!!! Instead of supporting war and rapists!!!!!

I’m wondering if you’re a descendant of Fred Wolki? Many years ago, while doing Archive research, I came across a report where fur trader Fred Wolki was attempting to buy a large boat or ship from the HBC. Fred Wolki was considered one of the wealthiest wage earners in Canada at the time, by the Canadian government. A result of the northern fur trade.

so sad, were not all drunks. too bad officers would say things like that I thought they had more knowledge than that (rank people) I stand with her

I stand with Esther Wolki.