Terrance Morin didn’t have childhood dreams of playing professional hockey growing up in Winnipeg.

Forget about going to college or learning a trade.

Morin’s dream was to join a gang and go to maximum security prison.

“That was my mission,” said Morin, 34.

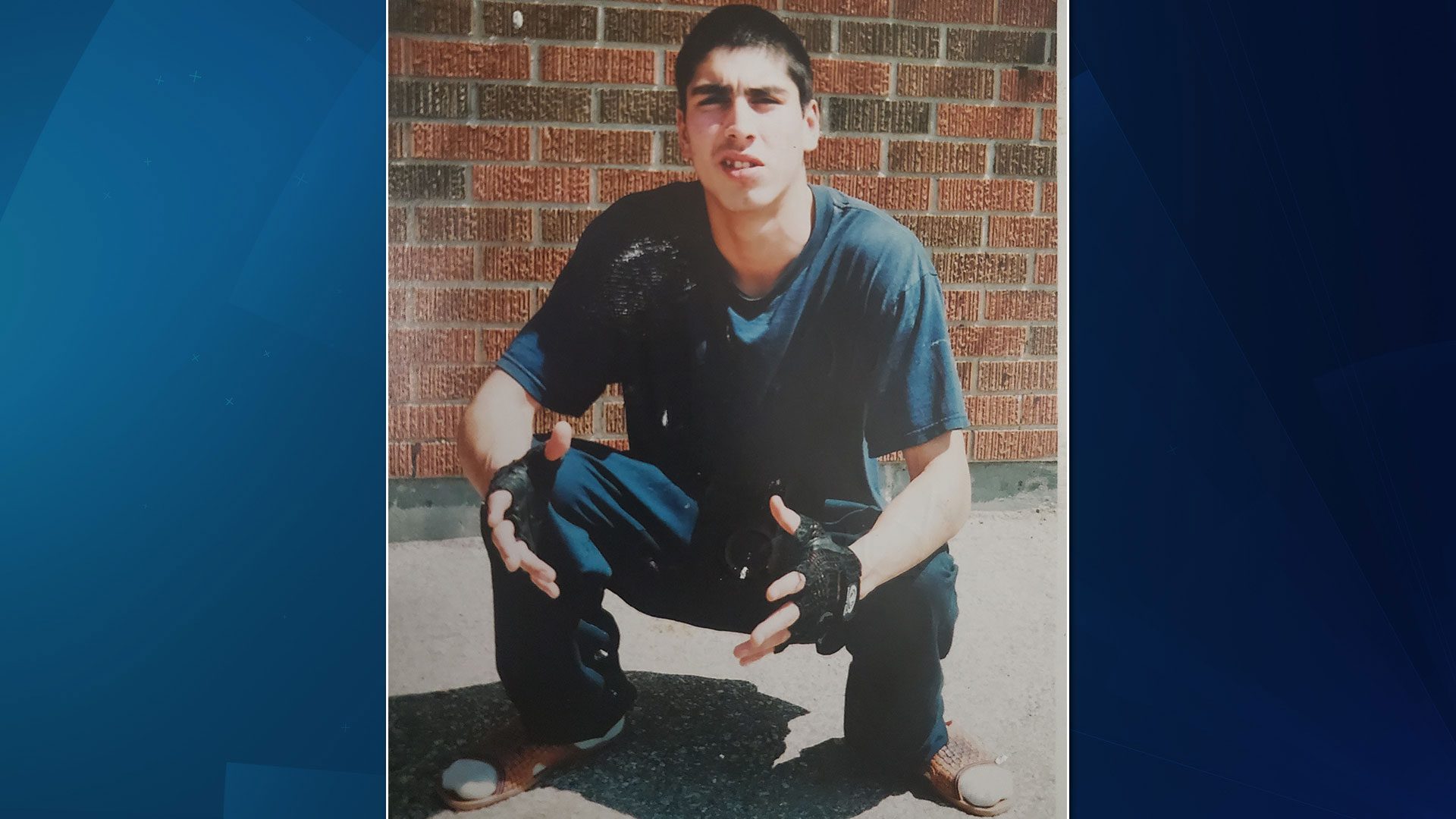

The same goes for Jeremy Raven, 37, who grew up in Winnipeg’s north end.

“As senseless as it seems, that was a thing to do,” said Raven.

“The older guys would get out of jail and they’d be like ‘have you been to jail, yet?’”

Raven was just a kid.

“It was just part of the environment, part of your circumstances and that’s the way I grew up,” said Raven.

He’s talking about extreme poverty — the ripple effect of government oppression across generations.

Joining streets gangs was their way out and going to jail was a badge of honour in that life.

Being in a maximum security prison was considered reaching the top.

Raven and Morin both said things haven’t changed today for far too many Indigenous youth in Winnipeg.

That’s maybe why there’s about 40 street gangs in the city that are largely Indigenous-led.

And the city’s never been so chaotic.

Random attacks.

Drug addiction.

The unsheltered.

Society sees it.

But refuses to see the trap it set.

How childhood trauma keeps ensnarling child after child into that life.

This is the inside story of Indigenous street gangs in Winnipeg.

Root Causes

Terrance Morin grew up surrounded by violence.

“I’ve seen my mom get beaten ‘till she was just on the ground crying, unconscious,” said the Anishinaabe father. “I’ve seen my mom drinking, taking pills, drugs.”

He didn’t know it then, but later in life he recognized this as childhood trauma.

The moment where his life in gangs took root long before he ever joined one.

“That’s trauma right, isn’t it? Growing up seeing that my whole life thinking that’s how we’re supposed to live, how we’re supposed to be,” said Morin.

He believed that he found a family in the brotherhood of gangs, at least at first.

“Sometimes gang members don’t treat their hommies good. They treat them like they’re less than them even though they rep the same flag, they have the same tattoos,” said Morin.

He explained he sometimes got “minutes.”

That means his fellow gang members beat him, trying to knock him unconscious for a minute. Several former gang members told APTN this was a common practice and usually carried out when someone messed up.

“Knock us out, inflict pain, whatever. Sometimes some guys don’t get knocked out they just f**king get deadly beatings. Some guys are hard to knock out. My whole life I’ve only been knocked out, like twice, but I got beaten up bad,” he said.

Morin started out as a striker in his gang, which means he carried out orders from those above him.

“I had to do everything. I was a striker for five years. That means little hommie. That means pretty much I’m out there basically like I was a soldier. I was a trooper. I’m trying to be Master Shredder, but I was one of those little foot soldiers for the longest time,” said Morin.

APTN met up with Morin this past September when he had just been out of the life for six months and on a new path focused on healing, ceremony and getting an education.

Morin was able to talk more freely about his former gang, because it no longer exists — some members are dead, others in prison for life or they’re living on the street.

Morin somehow made it through.

“I was a violent guy, but I didn’t have serious violent charges until I got incarcerated. I got more violent inside, just inside the system, than on the street,” he said.

Morin took APTN through the west end of Winnipeg showing where he grew up among various gangs, but was tight-lipped about providing details of opposition gangs.

“There’s obviously like a few different kind of gangs that, you know what I mean, I don’t want to speak of. It was just like there’s definitely gangland over here. I mean, like there were wars. There was like … shootings … stabbings,” said Morin.

Morin moved there at the age of 11.

“This is Broadway and Langside and right here this building, 212 Langside. This is where it all started. I used to live on a second floor right here,” he said.

Langside had other names, he said, like Shankside and Gangside.

He pointed out a former trap shack where “custys” (customers) got their drugs.

As Morin took us through the old neighbourhood, we approached Portage Avenue that acted as an imaginary line for competing gangs.

“This was like the borderline right here … some guys would stay on that side and some guys would stay on [the other] side,” he said.

As we continued, he suddenly told APTN to stop the car.

“I got robbed right there by gunpoint. Lobby right there. The shotgun right to my face, boom,” he said.

Morin was going to meet a custy and wasn’t carrying a weapon to defend himself so he gave up what he had.

He was lucky to survive.

“If you don’t have a strap, you need something like that in the city if you’re about that life, because you got guys that are eager to prove something,” he said.

Our trip soon took us to “Red Block” – the corner of Furby Street and Ellice Avenue.

“Oh yeah, right here. This is what they call Red Block. It’s very, ’till this day, gang orientated. This is a very dangerous neighborhood at nighttime,” he said.

Morin’s former gang operated nearby.

“See those girls just sitting there. This is where girls, they call it breaking. Breaking is another slang word for prostituting,” he said. “I went to school here. I used to live in this building right here. This is gang orientated, straight up.”

Morin told APTN in September that being out the life for six months still felt like being “fresh out.”

“Things started to drastically change for me in a good way just in this little while, because I want it this time,” he said.

And he’s doing it with the help of a friend and former gang member, Tim Barron.

Ceremony and the spiritual gangster

On a September evening a group of about 30 people met at 221 Austin St. North.

They make up the Mama Bear Clan and several times a week volunteers go throughout the community in Winnipeg’s north end offering sandwiches, bottles of water and other items people may need.

There’s a familiar face in the crowd.

“This is pretty much all we do. Just walk. This is the life. This is the life now. Giving back to the community. This is it,” said Terrance Morin, who now describes himself as a spiritual gangster.

Next to him is Tim Barron, 38, who led the smudging of the group before the walk began.

“Today, I found my purpose in ceremony, you know, like, that’s all I do is ceremony. I live in ceremony, in a ceremonial life,” said Barron.

“I come from a ceremonial family, and I didn’t know that. … It’s helped me find myself and find my spirit.”

Barron moved around a lot as a child throughout Winnipeg.

When his parents divorced things took a turn for the worse.

“I was really close to my mom, because there was a bond there with my mom. I couldn’t deal with my hurt that was inside from her leaving and I felt like she left me and neglected me and abandoned me. So I went to drugs and alcohol and what I should have done is talk to my dad about it and say I’m really hurt here,” he said.

He also turned to gangs to fill that void.

At least that’s what he thought he was doing.

He’d be in a gang for years, going in and out of jail where he kept finding himself alone.

Abandoned, again.

“I felt welcomed in the beginning. It felt like a brotherhood. But … I didn’t feel that love when I was in the jail cell by myself. Nobody really answered their phone except for my family. Some of them did, but not all of them,” said Barron.

In the end, it wasn’t worth it.

He had a lot of work to put in when he figured that out.

He needed to address the feeling of abandonment and childhood trauma.

“I felt that neglect and that abandonment and I didn’t think I was good enough,” he said. “I still feel that abandonment, except I can deal with it in a healthy way today. Before, I would just get triggered by it and then I would run to my old behaviors and old patterns.”

Hope in chaos

Mitch Bourbonniere sees the childhood trauma play out as a community outreach worker who has dedicated most of his career to mentoring at-risk youth in Winnipeg.

He grew up in the city and said things have never been this chaotic.

“We’ve had a really rough summer in Winnipeg. There’s been a lot of violence. Some of it’s been random and unprovoked. I worry about how chaotic things are today,” he said.

“It’s pretty crazy out there and the age of kids getting involved in gangs is a lot younger and it’s the younger guys that get taken advantage of by the older guys.”

Bourbonniere said it’s important to understand the root causes of the violence.

Colonialism.

Residential Schools.

Sixties Scoop.

Government violence.

“If we don’t pay attention to our young people, they’re going to stray. We have a lot of young people that are born into wounded families and wounded situations. I’m not assigning blame at all, because there’s a history in this country of colonialism and suffering, and there’s a consequence of that and … that is generationally wounded people,” said Bourbonniere.

Despite the growing violence, he doesn’t lose hope.

“The need in the community is overwhelming. I refuse to be pessimistic. I think the world in some ways is getting tougher and tougher and tougher, but in some other ways, it’s getting better and better and better,” he said.

“For every heartbreaking story I see, I see stories of triumph, as well.”

Bourbonniere points to Jeremy Raven, Barron and Morin.

He said they’re the role models for the youth today that they each never really had.

“Some days are hard, but then I remember the days that were harder, I have more good days than bad days because I’m free,” said Morin.

In telling their story, the three former gang members have a message for any at-risk youth caught up in the street life.

Something they wished someone had said to them.

“Get involved in sports. Finish school. Find the motivation to hang onto something and just keep moving forward. It does get better. The things that we may have went through as children, adults, that stuff can heal,” said Raven.

“I would just say to keep an open mind because like I’m just saying, it’s not a good life because I lived it. I experienced all that stuff, you know, selling drugs, being part of the gang life, dropping out of high school, because I wanted to make money, fast money. In and out of jail. That stuff’s not worth it, man,” said Barron.

“That’s not a life, right? It’s not a lifestyle you want to live. Maybe for the second you think you do, but once you get into that cell and you get a lengthy sentence, you’re going to realize that it was all a mistake,” said Morin.