A previous version of this story said that Indigenous Services had a name in their files – other than Lawrence Joseph Bear – for someone who may be Melvina Bear’s son. This is now understood to be incorrect, and APTN Investigates regrets the error.

The Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations (FSIN) in Saskatchewan has asked the RCMP to investigate a pair of cases from 1967 and 1982 involving allegations that hospital staff falsely told mothers their babies had died shortly after birth to possibly facilitate a deceptive adoption scheme.

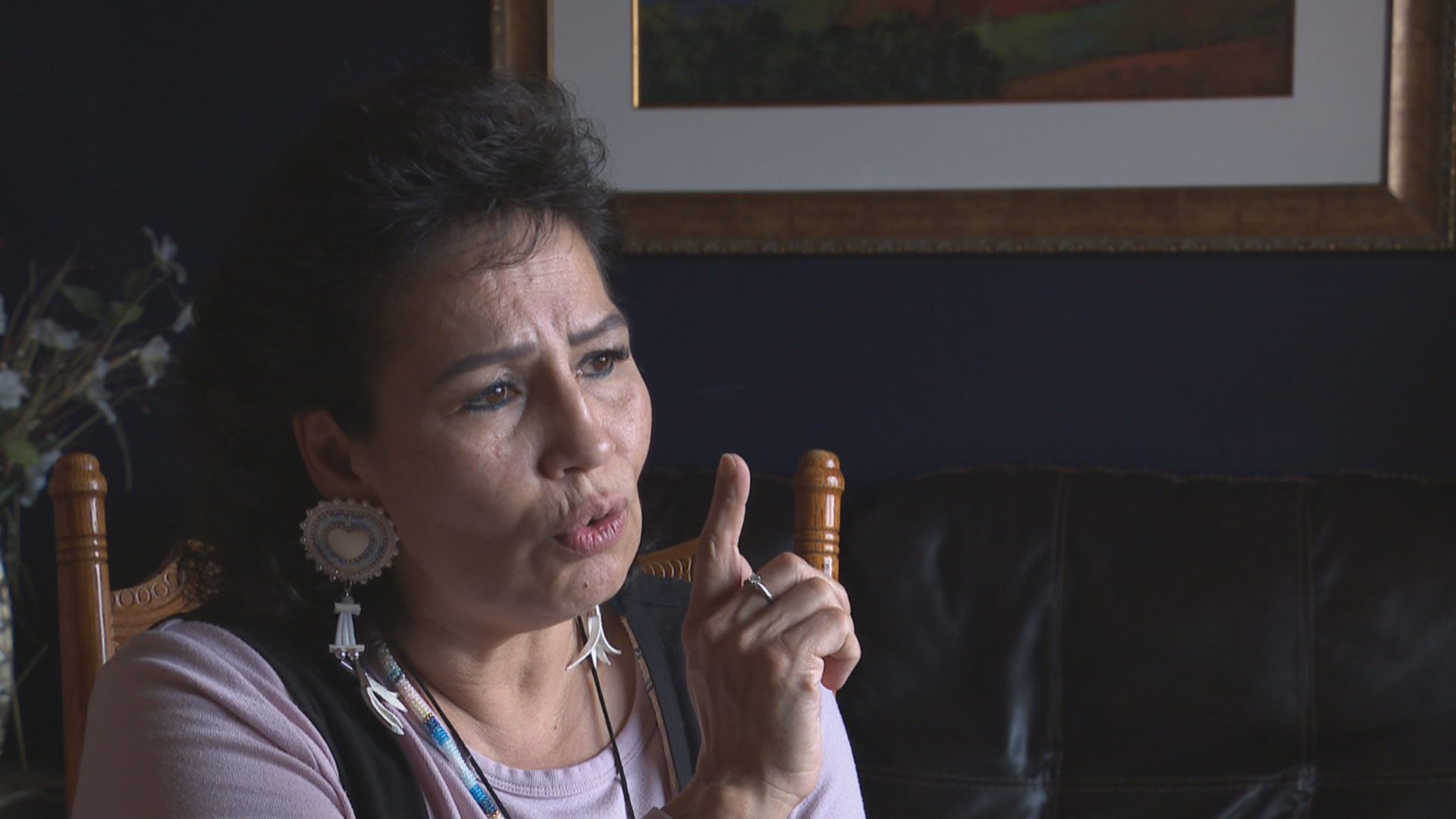

“The cruelty that was shown is just unthinkable,” says FSIN 4th Vice Chief Heather Bear, “as a mother, as a grandmother, I’m very disturbed.”

In both cases, Indigenous mothers were allegedly told by staff at hospitals their babies had died shortly after birth, but years later there are indications both of these infants may have lived.

The RCMP began looking into the FSIN’s files on this in 2021, but as of now, the investigation seems to have stalled.

The RCMP declined an interview with APTN Investigates but issued a statement indicating no charges have been made, and that the “RCMP is committed to following up on any new information received for either file and to keeping the families informed of any potential future developments.”

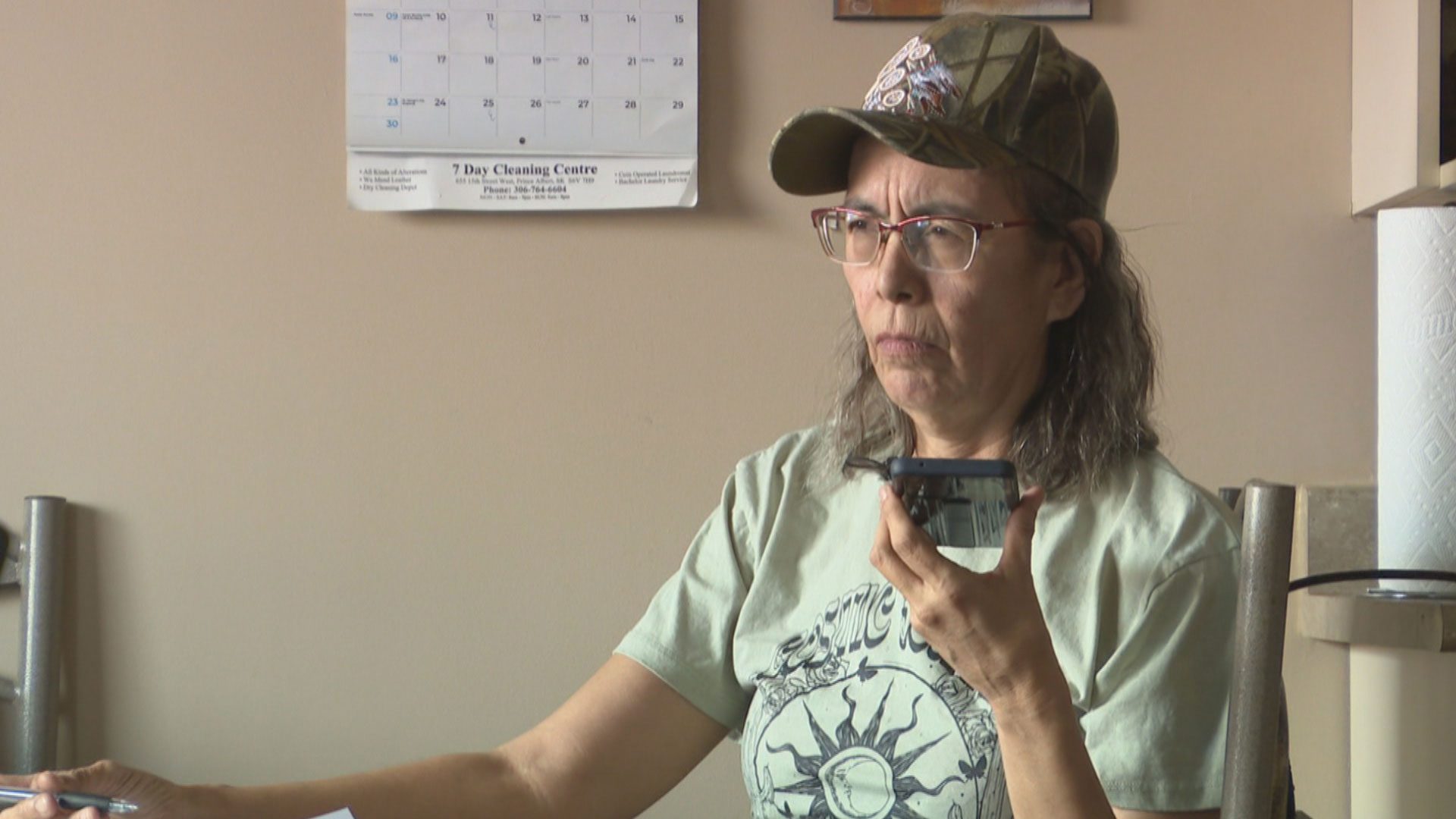

Melvina Bear – originally from Witchekan Lake First Nation – was 16-years-old and unwed when she went into Battlefords Union Hospital in North Battleford, Saskatchewan

She was complaining of abdominal pain and didn’t know she was pregnant, but soon found herself giving birth to a baby boy.

“And then the doctor right away, he said, ‘If your baby survives the night, we’re going to send them to Saskatoon,’ says Bear, “And they basically after he was born, they basically just like took him right away.”

Next, Bear says she was given medicine to put her to sleep.

“I’ve had seven other kids and I’ve never been given meds just to help me sleep,” says Bear.

Bear says at some point she was awakened and asked to sign forms.

“This could have been done at discharge night, not in the middle of the night after they said, ‘here’s your baby, he died.’, says Bear.

Bear was never given a body to bury, and was only given a baby to hold momentarily in her groggy, medicated state.

Years later, Bear was upset to discover her son’s name – Lawrence Joseph Bear – was on the band member’s list at Witchekan Lake First Nation.

To have her son’s name removed from the membership list, because as far as she knew he was dead, Bear attempted to obtain proof that he’d died.

Her first call was to Saskatchewan’s Vital Statistics department.

“I explained everything and then she goes, ‘I’ll put you on hold,’” says Bear. “It was a little bit of quiet and she comes back and she goes, ‘as of today as we are speaking right now, there is no record of your son’s death.’”

Next, Bear inquired with the federal government’s Indigenous Services department, and that’s when things got even more interesting.

On the phone, a staff member searching the status number her son was born with found a record that could indicate he’d applied for status card in 2000 when he would have turned 18 years old.

Melvina Bear is still waiting for an answer or any significant help – and a recent email update from Crown-Indigenous Relations Minister Marc Miller’s office doesn’t offer much hope the mystery will be solved soon.

The message from a press secretary and communications advisor to Miller’s office reads:

“…there are sensitivities, including privacy laws, surrounding Melvina’s issue which require us to take the appropriate steps in gathering the necessary information. Officials have been in regular communication with Melvina so they can assist in the search for her son.

“As of April 25, 2023 they have found a name match for the date of birth. However, there is no contact information associated with this name. They will continue working with Melvina and supporting her, to the best of their abilities, until she has answers. As the conversations between Melvina and officials are personal, we will not disclose their contents.

“It is not up to the Minister of Crown-Indigenous Relations to decide whether Melvina and her son should be reunited. Crown-Indigenous Relations’ role is to support Melvina by providing information and explore options – which takes time – to ensure it is done accurately and in a sensitive way, to avoid retraumatization. If Melvina’s son is located, it will be up to him to decide whether he wishes to proceed with next steps in contacting his mother.”

Inquiries with the RCMP have not yielded any further details, and they declined to answer questions from APTN about their investigation into Melvina Bear’s case and a similar case also passed on to them by the FSIN.

In March of 1967, Georgina MacDonald came into the Uranium City hospital from her home in Stony Rapids, Saskatchewan.

She gave birth and the baby was quickly taken away by a nurse.

MacDonald – who is from Lac Du Fond First Nation and who’s first language is Dene – described to APTN how she gave birth without any assistance from hospital staff.

“I was ringing that bell but there’s nobody,” says MacDonald, “So, a baby born on my back. And then what happened was nurse and doctor came in, the baby moving lots and she put her on her shoulder. I heard the baby cry. So she went out the hallway and I heard the baby still crying.”

Later, after awakening from sleep, MacDonald was allegedly told that her baby had died.

She pressed to see the body, but was, she says, told that it had been sent elsewhere for an autopsy.

Days later when speaking to a doctor at the hospital, MacDonald continued to ask to see her baby’s body.

Joan Strong is MacDonald’s daughter and tells the story of what happened next.

“Finally, the doctor said to her, ‘Your baby died because you’re an alcoholic,’” says Strong. “My mother has never drank in her life. I grew up with a sober, sober mother.”

Strong is assisting her mother in making inquiries related to what might have happened to her mother’s child born in 1967.

A sense that something was amiss prompted her to make some calls.

Oddly, Strong says Saskatchewan Vital Statistics told her they have no record of birth or death from March 1967 when

MacDonald went into the hospital in Uranium City.

She says she was also told by health officials that no records exist from Uranium City’s hospital – that they had been destroyed.

But then, there was a breakthrough.

Someone anonymously sent Strong a photo of her Mom’s hospital record, a file listing her Mom’s visits – including the one when she gave birth in March of 1967.

In another odd twist, an original entry for the 1967 visit has been covered with correction fluid and written over by hand.

But it indicates that Georgina was there for OBS, that is, an obstetrics-related visit.

Later, when the RCMP investigated Georgina MacDonald’s case at the request of the FSIN, Strong says they were able to subpoena the same document she’d been sent a photo of.

Naturally, MacDonald and her family would like to know what happened to that baby – and why there is no record of death or birth.

APTN asked the RCMP whether any attempt had been made to determine what was written under the correction fluid on Georgina MacDonald’s chart, but they did not provide an answer.

The RCMP did however issue the following statement:

“Saskatchewan RCMP has fulsomely investigated both files, with the assistance of agencies including the Saskatchewan Coroners Service, Saskatchewan Health Authority, the Alberta Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Saskatchewan College of Physicians and Surgeons, Athabasca Health Authority, Indigenous Services Canada, Vital Statistics, Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada and Saskatchewan Ministry of Social Services.

“Investigators have provided updates to the families through this investigational process. No charges have been laid. Generally speaking, Saskatchewan RCMP does not comment on the specifics of its investigations to protect the privacy of the parties involved, and to preserve the integrity of any potential resulting court process.”

In the meantime, Joan Strong is going to keep pushing for answers.

“I’d like my parents to have closure – I want my parents to know where their baby is,” she says, “I don’t know if this child is ever going to want to know us.

The saddest thing I heard my mother say was what if my child doesn’t want to be with us. What if my child doesn’t like us. No mother should ever ask that. We come from a loving mother.”

“My mother wasn’t even given the honour to even touch her child,” adds Strong. “This is totally not a sixties scoop. This is friggin’ abduction. This is criminal negligence. This is right from her womb. I don’t even like to describe what this is. This is not right.”

Her Mom’s story – and Melvina Bear’s too – is now on the radar of Métis academic Allyson Stevenson, faculty member in Indigenous Studies at the University of Saskatchewan and author of Intimate Integration: A History of the Sixties Scoop and the Colonization of Kinship.

“I did not come across any of those types of stories in the records that I reviewed, but it’s not to say that I haven’t had people share similar types of concerns with me about experiences in their family that they’re looking to find more information about them,” says Stevenson.

As the title of her book indicates, Stevenson sees the policies of apprehending Indigenous children and giving them up for adoption to white families as the “colonization of kinship.”

“Colonization is often seen in terms of land and resources, perhaps health and legal and governance structures, but looking broadly at various ways in which the Indian Act specifically targeted gender relations, marital relations and child-rearing, I saw this child removal adoption as a form of colonization of specifically kinship, Indigenous forms of kinship and caring that were deeply embedded and important for Indigenous nations,” says Stevenson.

But Stevenson says that schemes like the ones MacDonald and Bear may have been victims of, are especially awful.

“It’s appalling. It’s criminal, actually. It’s a criminal offense,” says Stevenson,

“So I think it requires follow-up. And I think we need to really understand what’s happened with these children and what’s happened to these women.”

Heather Bear with the FSIN agrees and she is hoping more women come forward.

“I look at the forced and coerced sterilization of Indigenous women and girls,” says Bear. “We started with a handful of ladies, women. And I think we’re nearing 100, you know, in terms of a class action…. We don’t know who, how many, but we know there’s stories of others.”

And Bear doesn’t stop at invoking the possibility of a class action lawsuit.

“We call on the province, the federal government, whoever it may be, to have an inquiry,” says Bear.

APTN would like to hear from women who think they might have experienced something similar too.

In researching this story, APTN found a published account from 1989 about a Mom who was lied to by social workers and told her baby had died 39 years previously, in order to clear the way for an illegal apprehension and adoption of her son.

Edna Carnell was joyously reunited with her son Warren Clark, and APTN is hopeful it can put a spotlight on this phenomenon and ultimately assist in reuniting other mothers with their stolen children – starting with Melvina Bear and her son, Lawrence Joseph Bear.

If you have a similar story to share, please reach out to reporter Christopher Read.