Terms like voter suppression and disenfranchisement are being used in relation to various situations affecting Indigenous voters in the federal riding of Kenora this past election.

In Disenfranchised, APTN Investigates visits Kenora to probe why services provided by Elections Canada to a handful of First Nations communities were unsatisfactory to some.

Elections Canada is doing its own investigation, having been sent a report detailing alleged service failures by the NDP’s Indigenous Get Out the Vote Coordinator for the riding, Tania Cameron.

“For me, it was concerns about disenfranchisement of First Nations voters – in other words, voter suppression,” says Cameron of why she needed to write to Elections Canada.

“I was really, really upset by what happened and what I learned on election day enough so that I had to take a week to form that letter and I’d keep going back to it because I didn’t want to be so angry,” says Cameron, adding “but I was just disappointed, disgusted.”

Cameron, a previous candidate for the NDP in the riding, says she is concerned enough about how the election was run that she would like to take over the position of returning officer for Kenora.

“I’m ready to take a step back from partisan politics if it means that I can help the First Nations people get out to vote on Election Day, help them do their jobs as poll workers engage the voter,” says Cameron. “I would rather do that and than be part of partisan politics.”

Cameron has been collecting stories about things that happened which made it more difficult for Indigenous people in the area to vote this election.

One of the people who got in touch with Cameron is Angie Petiquan.

Petiquan is the health director at Wabauskang First Nation and that has something to do with why she was so eager to vote this election.

“I was following this election because PC and the Liberals were at a tie, almost tied all the way, so I wanted to go vote,” says Petiquan.

“I was very worried about the health care system,” she adds, “I heard if one party got in that it was going to turn into privatization of health care and I don’t know if it was rumours, but I was scared. So I wanted to go vote.”

Election day was busy for Petiquan, but she’d set aside some time to vote with her adult son in the afternoon after she’d run some errands in Dryden.

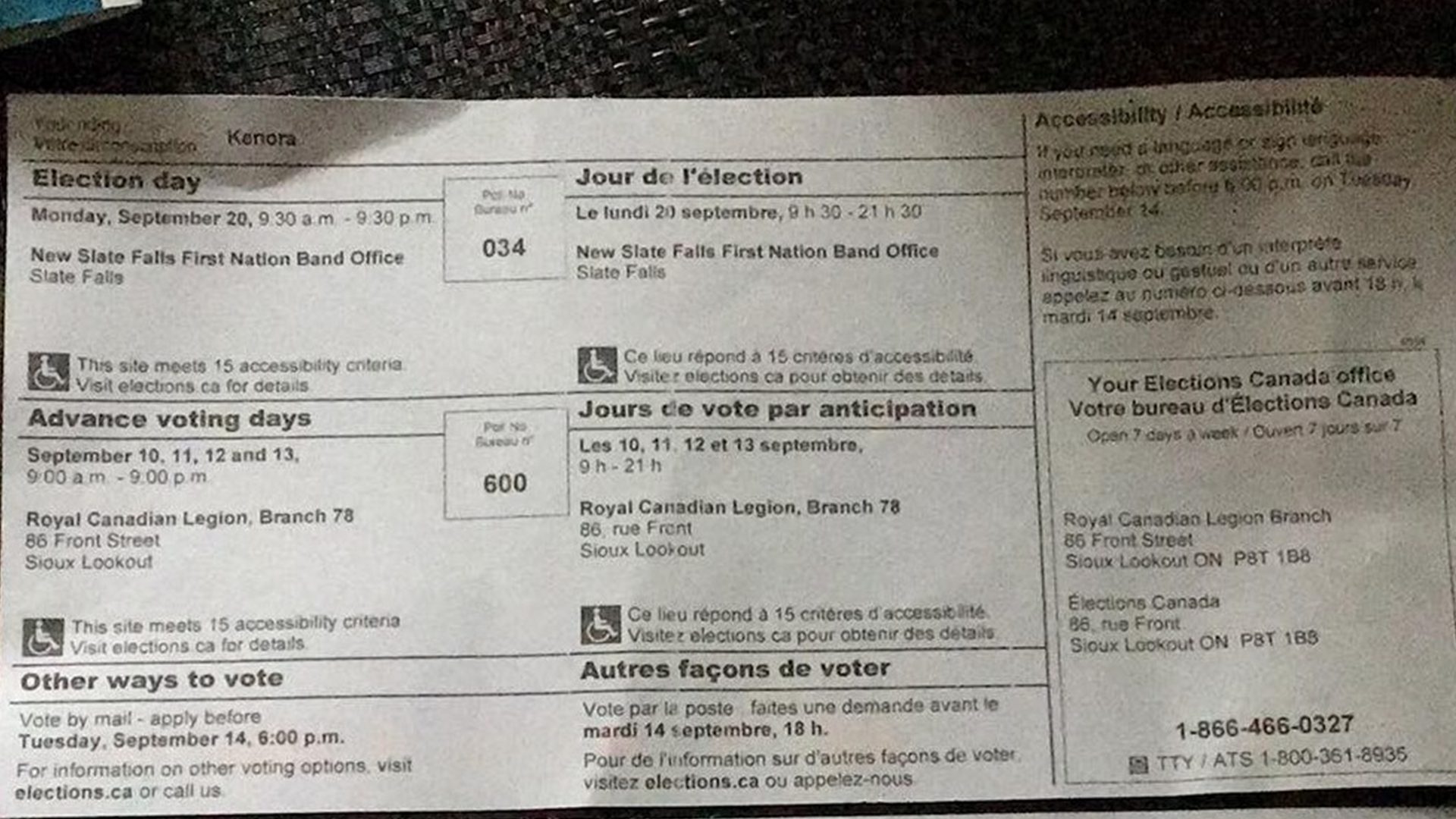

But then she checked her voter information card and realized it was telling her to vote in Slate Falls First Nation – about a six-hour drive away from Wabauskang.

Her son, who lives with her, had a card telling him to vote in Vermillion Bay – about an hour away.

Petiquan and her son had been expecting to be able to vote in Ear Falls – which is only a half hour drive.

And so, tired from her day of errands, Angie Petiquan decided not to vote.

“I felt really disappointed, and I felt like I didn’t matter,” says Petiquan.

Later that evening while she watched election news coverage, Petiquan logged onto Facebook and saw a post from her friend Tania Cameron.

“I saw her post saying ‘Is anybody else having trouble voting?,’” says Petiquan.

Cameron put Petiquan’s story into her letter to Elections Canada’s Chief Electoral Officer, Stéphane Perrault.

Also included in the letter were details about how Elections Canada provided advance polls, but not polling stations on election day in three First Nations communities in the Kenora riding – Cat Lake, Poplar Hill, and Pikangikum.

It would appear that these communities didn’t get polling stations on election day as a result of an arrangement made with Elections Canada to attempt to accommodate traditional activities such as hunting which normally occur in the period when the election was scheduled.

But Elections Canada says that not providing a poll in those locations on election day is something they regret.

“Being able to count on having a poll on Election Day is our minimum standard of service,” says Lisa Drouillard, director of Field Governance and Personnel Support for Elections Canada.

“There’s a lot of different sides to the story and some communications breakdowns, so we really need to hear from everyone and all the different parties involved in this to determine what happened and to make sure it doesn’t happen again, because this is something we take really seriously and we always really sincerely apologize any time there’s a voter who wants to vote on their election day and can’t do it or has a hard time doing.”

The Chief of Cat Lake, Russell Wesley told APTN that he was not aware that by taking the advance poll, his community opting out of a poll on election day.

Elections Canada says a main focus of their investigation is looking at whether it was communicated to leadership in these communities that agreeing to the advance poll meant they wouldn’t get a polling station on election day.

“That’s the real nub of the further digging that we have to do,” says Drouillard, “because clearly we do have a very clear message that went out from the returning officer to the candidates that made it very clear that that was the arrangement that he made with the chiefs, that it was going to be on the advance poll day and not on election day.”

APTN requested an interview with Kenora’s returning officer but was instead offered Drouillard as spokesperson.

On the issue of Wabauskang residents being directed by their voter information cards to vote far from their community, Elections Canada sent APTN a statement.

It reads, in part, “In this situation, we were able to find five electors who, according to their data source, should be located in the community of Wabauskang 21. However, in the information contained in the National Register of Electors, they were associated with streets located in different communities.

“This led to them being geocoded to different polling divisions, and therefore to polling places that were further away, up to six hours away from their house. This shouldn’t have happened and we apologize to those electors.”

Elections Canada has not set a date for when the report associated with their investigation into this will be released, but they say it will be made public.