The families who have lost loved ones in police custody in Prince George, British Columbia continue their quest for answers and justice.

At the same time, calls for eliminating systemic racism in policing in Canada get louder.

Three years ago, Dale Culver died during an RCMP arrest in Prince George.

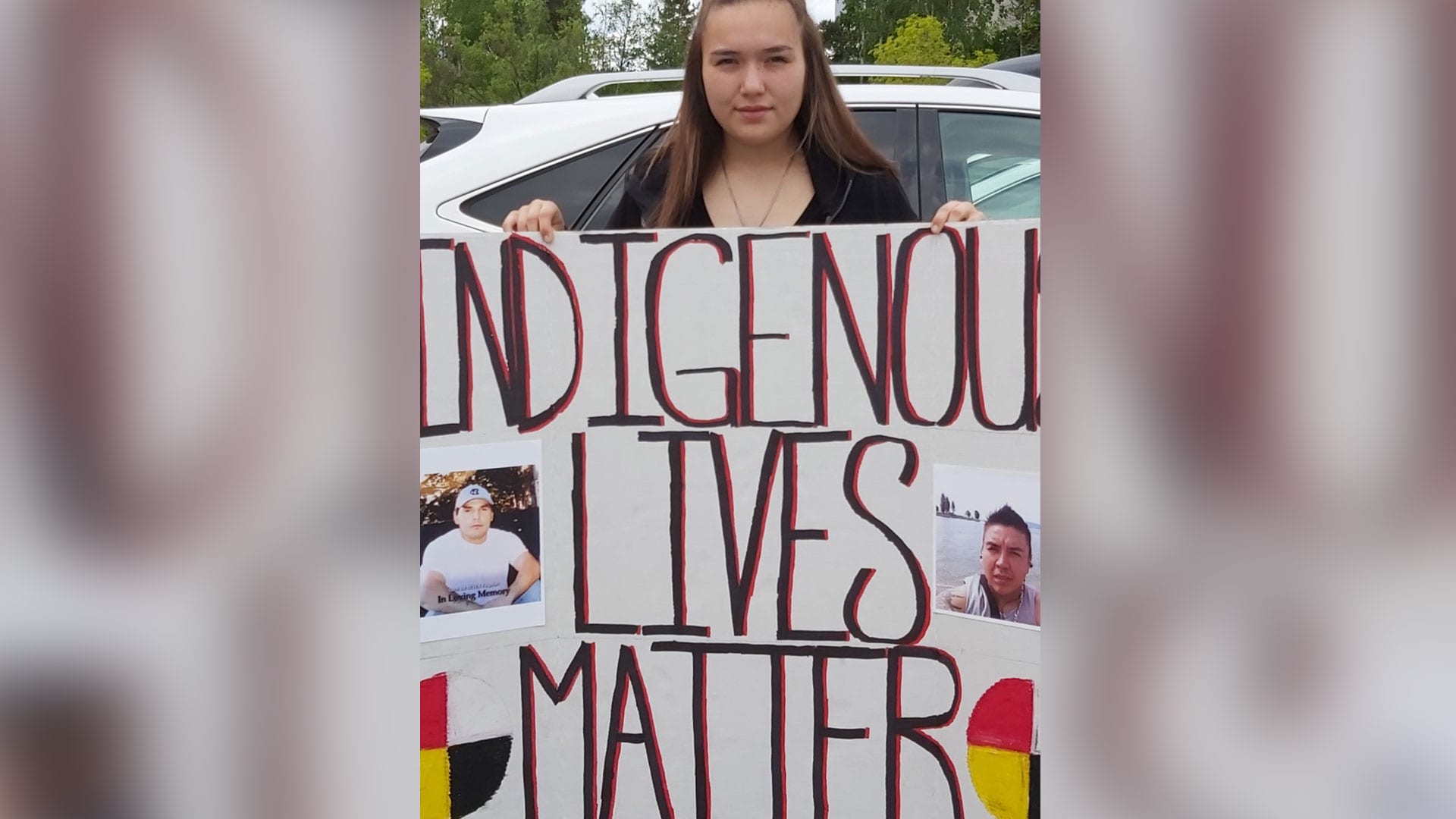

His daughter, Lily Speed-Namox, has been looking for answers ever since.

“There’s been no apologies from any RCMP. Not even just the general RCMP public as just general. I’m sorry that this happened to your family, that our people have done this to your people,” she said.

The Independent Investigation Office of BC recommended five charges against RCMP officers.

The crown attorney is conducting a charge assessment but there’s no timeline on when a decision will be announced.

After George Floyd’s death in the United States, Black Lives Matter rallies erupted around the world, calling for police reform.

The rallies started to take place across Canada.

In the summer of 2020, Lily Speed-Namox spoke at a rally of hundreds of people who marched Prince George’s streets.

She raised questions of justice for her father and others.

“It was definitely empowering, I suppose, not just to myself, but to my dad’s story and to the culture,” she said in an interview. “I got to share my honest, true story and feelings about how I felt and what happened without anybody telling me, no, you can’t say that.”

Speaking at a Black Lives Matter rally was part of Lily’s healing journey as she deals with the loss of her father.

“It’s very I want to say comforting, but not necessarily comforting because it’s sad that it has to happen. But it is uplifting that it is something that is starting to get acknowledged and recognized as a problem,” she said.

At the same rally, Terry Teegee, Assembly of First Nations regional chief for British Columbia, marched and spoke to the crowd.

“With the movement, with the death of George Floyd and also the death of many black folks and brothers and sisters in the United States and Canada really highlighted, I think that’s really with covid, this pandemic really highlighted the systemic issues and the societal issues of the United States and perhaps even Canada,” he said.

“I think, you know, black lives matter and Indigenous lives matter. It’s really very similar in terms of the issues that we face.”

In April 2020, Teegee’s cousin, Everett Patrick,42, died after going into medical distress at the RCMP detachment in Prince George.

“You know, being a family member, it’s very sad because, you know, we don’t have you know, Everett Patrick has left children behind and, you know, relatives of mine that, uh, you know, have loved ones that are that are gone now, so it’s certainly sad,” he said.

Then in October 2020, his cousin’s son, Chad George, 23, also died in custody.

Natasha George, Chad George’s mother, shared his story with APTN News in the northern B.C. town Vanderhoof, an hour west of Prince George.

As the interview started, the sound of a train passing made her pause. The sound of the train reminded her of her son.

“So the train just went by and when me and my son spent a lot of time together — it just went by,” said George. “So right now I’m talking about him and it just seems like a sign and it’s like him saying wahoo, you’re telling my story.”

Chad George grew up in Hazelton, but he spent the majority of his life in Prince George.

He and his mother both spent long periods homeless.

On October 1, 2020, Chad George was picked up by the RCMP for a prior legal matter. He died a few days later in the Prince George Regional Correctional Centre.

“Right now they’re investigating his death. There’s still a separate coroner’s investigation going on and the RCC (Prince George Regional Correctional Centre, I think, is still under investigation,” said George’s mother.

After an investigation, the Independent Investigation Office (IIO) of BC cleared the RCMP of any wrongdoing.

The Prince George Regional Correctional Centre is conducting an internal review of his death.

And Chad George’s family awaits a coroner’s report.

His mother, Natasha George, hired a lawyer and is looking for answers.

“Even if it hurts, I want the truth. And then I could take action and if it was wrongful death, I want justice and I’m going to work for it and I’m going to, like, follow up with leads and I’m going to pursue it,” she stated.

“I’m not going to give up because my son meant the world to me and his life was precious to me.”

Three men, all related, died in custody in Prince George within three years.

Everett Patrick died in April of 2020 with very little media coverage.

One month later, George Floyd died in the United States after an officer kneeled on his neck for eight minutes and 46 seconds and a movement calling for changes swept around the globe.

Erick Laming is completing his doctorate at the University of Toronto in Ontario. He is a member of the Shabot Obaadjiwan First Nation in Ontario.

“I think it has the potential to make great change. But the problem with these changes is that they’re always so slow in coming and we won’t know the effect for years to come,” he said of global Black Lives Matter rallies.

Lily Speed-Namox hopes that global outcry for change leads to police accountability at home.

“I hope for justice, I hope for justice, not only just for my dad, but for all the other people that have died in police custody. Everett, Everett Patrick, my cousin Chad, who died in police custody not that long ago. And for anybody else, George Floyd or anybody else that has ever died in police custody is who I’m speaking for,” she said.

Laming believes the amount of time families are waiting for answers needs to change for all involved.

“That’s something that these investigative units, the civilian watchdogs are trying to improve on. They’re trying to have an investigation done within a certain timeframe because it’s not good. A delay is not good for anybody, it’s not good for the officers, it’s not good for the affected person, it’s not good for the families involved,” he said.

He also stressed the importance of each province and territory having their own independent oversight bodies for police officers.

“Those exist in seven, seven provinces right now. So, I mean, we still have almost half the country that do not have one of those bodies in the province or territory. So, I mean, that’s something that that needs to change, right up,” he said. “We need every province and territory needs to create their own body to investigate policing in that jurisdiction.”

The RCMP doesn’t track ethnic-based data concerning deaths in custody or individuals who suffer serious harm.

Laming believes that is a key to change along with better oversight.

“It’s a huge problem and that’s kind of leads to the systemic problems that we see in terms of racism. I mean, if you, if you can identify problems, if you don’t have those statistics of those numbers to see that there are patterns, then there’s a problem with the whole system’s kind of corrupt in that sense,” he said.

APTN Investigates sent an interview request to RCMP headquarters in Ottawa. They sent an emailed response on the steps they intended to take to eliminate systemic racism but they did not consent to sit down for an interview.

“We have developed an RCMP Equity, Diversity and Inclusion Strategy, with a focus on identifying and reducing workplace and service delivery barriers, racism and discrimination for diverse groups of people,” said Cpl. Caroline Duval from RCMP media relations in Ottawa.

“We know we can always do better, and we remain committed to building an organization that respects all people, values diversity and fosters inclusion.”

The RCMP plan to modernize is called the Vision 150, which includes establishing an Indigenous Lived Experience Group, an office for RCMP-Indigenous Co-Development, Collaboration and Accountability, and improvement requirement by being proactive in diversifying and trying to reduce bias.

LINK HERE https://www.rcmp-grc.gc.ca/vision150/index-eng.htm

Criminologist Eric Laming said it sounds positive but questions the lasting power and impact.

“When is it going to be implemented? It doesn’t have the sustainable funding to keep going. Does it have the right people involved to kind of keep it going as well? Those are the things that we have to always look for,” he said. “But on paper, it sounds good. I mean, all of these initiatives sound promising. It’s just we’ve heard the same things year after year to improve the relationship between Indigenous peoples and police.”

It’s been eight months since the start of the investigation into the death of Everett Patrick.

The response to our calls and emails asking for coroner’s reports remain the same, it’s under investigation.

The family of Dale Culver has been waiting more than three years.

No one at Prince George’s RCMP would go on camera but they did provide an emailed statement.

They said the Privacy Act limited the amount of information they could provide.

“With respect to your next question, internal conduct is subject to Privacy Act restrictions and only in those cases where the matter results in a Conduct Dismissal Hearing would the case be a matter of public record,” Sgt. Janelle Shoihet, Senior Media Relations Officer at RCMP E Division headquarters wrote in response to our inquiries.

In both cases, police officers are back on active duty.

“The officers involved in the Dale Culver matter have all returned to active duty with their respective units. On the same token, the officers involved in the Patrick matter remain operational and assigned to the Prince George RCMP,” Shoiet wrote.

Three-and-a-half years after the death of Dale Culver the RCMP officers involved in his death are still working.

The RCMP could end up in court here in Prince George facing the charges recommended by the IIO.

Culver’s daughter reacts to the news that officers are still working.

“It’s just uncomfortable to know that these people are still roaming the streets,” said Lily Speed-Namox.

Lily’s mother Tracey Speed expressed frustration.

“It’s very disheartening to know that they’ve taken two people’s lives and they can just take more people’s lives,” she said. “ It’s really sad that they can still go on and if they were anybody else in society, they would not be still working, let alone walking the streets.”

She would like to see an improvement in RCMP training.

“I’d like to see reform in the training process of the RCMP, like they have to understand how to deal with people,” said Tracey Speed.

Lily Speed-Namox wants justice for her father.

“I know that he wouldn’t be dead if it weren’t for you. So I’d just like an apology and to see justice made for these people that have killed multiple people now and are still working and in our society, it’s not okay.”

The Crown Attorney can take three years to decide whether or not to move ahead on recommendations from the Independent Investigations Office.