Watch Part 1 of APTN Investigates: Refugees in our Land – Click here

The yellow flag is up – three minutes to race time.

Scott McQueen unhooks a dog from his truck and rushes him over to his son Taltson’s sled at the starting line.

McQueen’s daughter, Jordee Reid, takes a knee next to the animals and holds their collars tight to keep them at bay until the word is given.

Green flag is up – one minute to race time.

Large crowds of families and spectators have gathered around the racers – it’s almost time.

McQueen puts his arm around his son and gives him some last minute advice, as a voice comes over the speakers, counting down from 10.

The green flag drops.

Taltson McQueen untethers his sled and his dogs break into a run, setting a fast, but steady pace that they will fight to maintain over the next three hours.

For the last 67 years, mushers from across the country have gathered on the shores of Yellowknife Bay to celebrate their culture and tradition.

The Annual Canadian Championship Dog Derby is held on the frozen ice of the Great Slave Lake. The three day, 150-mile race is a test of skill and endurance that’s been passed down through the generations.

“The dogs determined your quality of life in the north,” Scott McQueen says, from his family’s cabin on the outskirts of Yellowknife. “The better quality of dog team you had, the better life you lived.”

For McQueen, dog mushing isn’t just sport or recreation – it’s a way of life. His father, Danny McQueen, was a champion musher who dominated the races in the 1960s.

It’s a tradition that’s keeps the family connected to their culture and identity.

“People on the Taltson River, especially my family, they took a lot of pride in being able to train sled dogs,” McQueen says. “It’s something that became just second nature to our family, to work, train and to care for sled dogs.”

McQueen’s family hails from Rocher River, Northwest Territories.

The historic community, located on the east bank of the Taltson River, was home to Tthetsënɂotı̨́né or Yellowknives for generations.

Rocher River was abandoned by the federal government in the 1960s, in part so they could develop the Pine Point mine, less than 100 kilometres away from the community.

In order to power the mine, the feds proposed the construction of the Taltson River dam – a decision that would have lasting impacts on the environment and the people.

“I was too young when the dam project was being constructed,” McQueen remembers. “But the sense I’ve gathered since then is that people felt they had no choice. It’s what the government was going to do and they were right. If the government wanted to take the land, they went in and took it.

“The people knew they didn’t have a choice, so they started to make plans to relocate their lives and begin a new life someplace else.”

APTN Investigates heard similar accounts from a number of communities where the Tthetsënɂotı̨́né people were relocated.

“I look at it as slavery, I look at it as political slavery, where the government controls everything we do,” Ronald McKay says, from him home in the small hamlet community of Deninu Ku’e, also known as Fort Resolution, Northwest Territories.

“We had human rights before they came here. That’s been taken away from us too.”

Like many of the residents in Rocher River, McKay’s family was forced to relocate to Deninu Ku’e by the federal government.

Over the years, he has done much of his own research on the history of his people and what really happened in Rocher River. He says it can all be traced back to the signing of Treaty 8.

“I have a copy of the Treaty 8 document here,” McKay says, as he pulls a large file folder from his desk. “For the Yellowknives, Chief Snuff signed for the lower part of Taltson River called Rocher River. So this document in itself proves who signed for who.”

The document is historic evidence that the Tthetsënɂotı̨́né of Rocher River, were original signatories to Treaty 8 as the Yellowknives.

Guaranteeing their inherent rights would be protected and the land maintained for future generations.

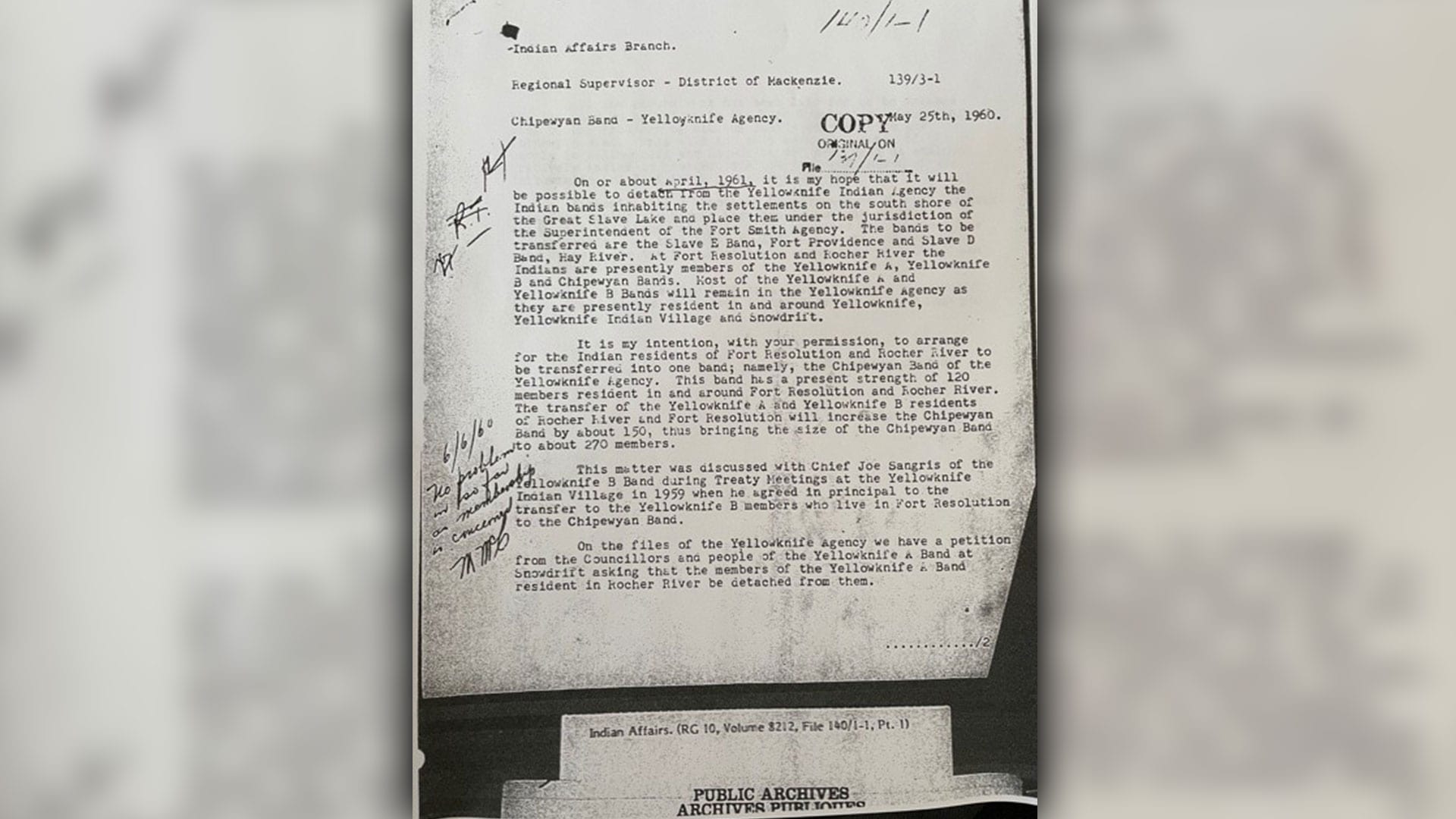

McKay takes out another document from his files, a letter from the regional supervisor, District of Mackenzie, Indian Affairs Branch, dated May 25, 1960.

The letter outlines the federal government’s decision to transfer Tthetsënɂotı̨́né people of Rocher River to what was then called the Chipewyan band in and around the community of Fort Resolution.

“I see it as genocide, when you take away a person’s identity, their culture and their title,” McKay says. “They’ve taken us from who we are and put us in another band. So we have no idea of where we’re from. And where we belong.”

Over the years, there have been many attempts to reinstate the Rocher River band with the federal government.

Scott McQueen and his family were part of the most recent push back in the late 90s.

“Basically the federal government said that they weren’t going to open any negotiations with a new group,” McQueen remembers.

“If we wanted to be included in negotiations, we had to get the Akaitcho to agree, which they refused to do, in part because each of the negotiating Akaitcho groups had something to lose.”

The Akaitcho have been negotiating a land claim agreement with the federal government for the last 30 years.

They are made up of three First Nations in and around the south side of the Great Slave Lake – the Deninu Ku’e, the Lutsel K’e dene and the Yellowknives Dene First Nation.

It’s a traditional name that the Tthetsënɂotı̨́né of Rocher River maintain was taken away from their people.

“The Yellowknives Dene from Ndilo, Dettah took the name of the Tthetsënɂotı̨́né people – the Yellowknives,” McQueen insists.

“The Fort Resolution, Deninu Ku’e took the land area, and the Lutsel K’e First Nation, they got the actual band memberships. And so this injustice that the federal government created is perpetuated by these other groups because they stand to lose something.”

The question of who the original Yellowknives Dene are remains a contentious and sensitive issue for the Akaitcho to this day.

The Yellowknives Dene that inhabit the communities of Ndilo and Dettah are also recognized as T’satsaot’ine, and also have rights to the traditional name.

In the end, talks with the federal government fell apart.

“I guess it wasn’t unexpected,” McQueen says. “They don’t want to have to compensate people. If they can put the blinders on and pretend that didn’t happen, that’s a benefit to them.”

Read More:

Displaced people of Rocher river, N.W.T. fight for recognition

APTN reached out to the federal department of Crown-Indigenous Relations for comment.

We wanted more information about the decision to force the Tthetsënɂotı̨́né people of Rocher River to join other bands across the north.

The federal government’s reply only reinforced what the displaced people of Rocher River have been saying for decades:

“We are working collaboratively to advance reconciliation and renew the relationship with Indigenous people in Canada based on the affirmation of rights, respect, co-operation and partnership,” the statement said.

“The historic community self-identified as Rocher River has never been recognized as a band under the Indian Act and to date, Canada has not received a claim to negotiate from this group.

“There are currently two comprehensive claim negotiation tables led by Canada in the region that includes Rocher River; one with the Akaitcho Dene First Nation and one with the Northwest Territory Métis Nation. Those two processes are the avenues to address rights Rocher River may have.

“The Akaitcho Dene First Nation represents the interests of the Yellowknives, the Lutselk’e and the Deninu Kue First Nations at the comprehensive claim negotiation table. The Northwest Territory Métis Nation represents the interests of the Metis in Fort Smith, Hay River and Fort Resolution.

“Ongoing negotiation details are confidential to the parties.”

Back on Yellowknife bay, the Canadian Championship Dog Derby has entered the last day of the races.

Scott McQueen’s son, Taltson, named after the river his ancestors lived on for generations, is representing the family, carrying on a tradition that was passed down from his grandfather, even though it’s been over 60 years since the community of Rocher River was abandoned by the federal government and the people forced out.

If today proves anything, it’s that the legacy and the history of the Tthetsënɂotı̨́né will live on, he says.

“You can’t move forward with reconciliation if you’ve taken the land from one of the Indigenous land owners and you haven’t made amends with them,” Scott McQueen says.

“You haven’t given it back, you haven’t negotiated with them, some sort of process to compensate them for that. Without that there can’t be reconciliation.”