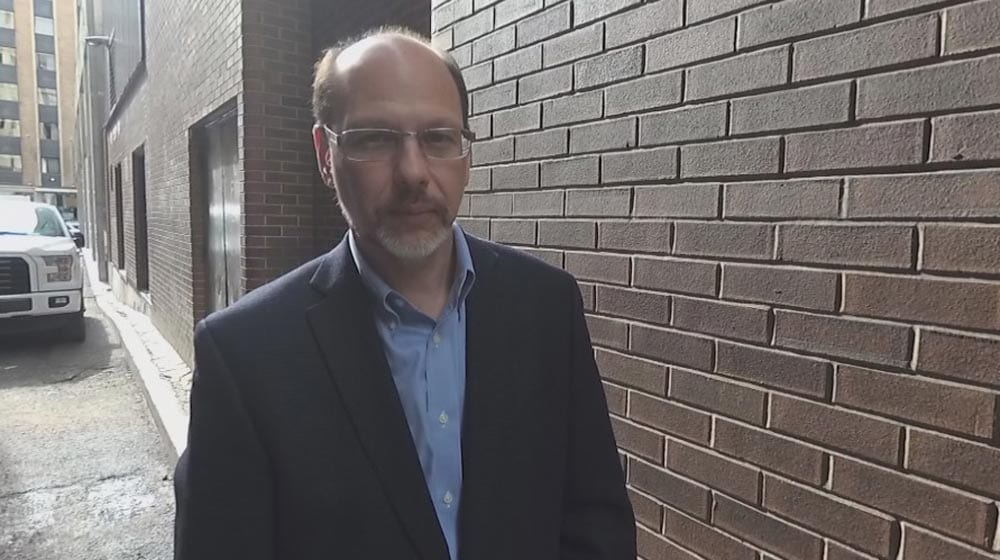

At 52 years old, Dan Parlow has spent more than half his life, over 30 years, behind bars.

Parlow is Anishinaabe, originally from the Batchewana First Nation, near Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario.

Like many Indigenous children of his generation, he was taken off his home reserve and away from his mother at just three months old — a victim of the 60s Scoop.

Parlow was adopted out to a non-Indigenous family. It was the first of many homes where he suffered years of abuse and neglect at the hands of his “caregivers.”

It was a chaotic upbringing that he calls a pipeline to prison.

(APTN Investigates met up with Parlow to discuss the growing over-representation of Indigenous people in Canada’s criminal justice system.)

“Numerous group homes, foster care, later on to detention homes, training schools, provincial jails and then penitentiaries. I didn’t have much hope, I was very lost and didn’t know who I was. There’s a lot of painful experiences that came out of that, a lot of things I regret, that I did to myself and others.”

Parlow eventually ran away from foster care and found himself living on the streets. He soon turned to a life of crime, was convicted of armed robbery and sentenced to 18 months at the Guelph Correctional Institute.

He was only 16.

“There was no Young Offenders Act back then, so you’re a 16-year-old boy going into a man’s prison,” Parlow told APTN. “It was traumatizing, it was traumatizing. I refer to it as the ‘University of Crime,’ as it progressed right.”

Parlow spent the next three decades battling drug and alcohol abuse, both in and out of provincial jails and federal penitentiaries. His charges included conspiracy, various assaults, robberies, and firearms violations. Once ‘inside’ he learned how to be a better criminal.

“The institution itself, the policies and the actions that take place in there from corrections, made me in many ways,” Parlow recalls. “I was a lost individual, and full of a lot of pain, feeling like I had no connection to this world and you know, you live that way.

“I honestly didn’t’ think I’d live to see 25.”

Dan Parlow’s story isn’t unique…

While Indigenous people make up just under five per cent of the Canadian population, they now account for over 27 per cent of all inmates incarcerated in federal institutions.

The situation is even more distressing for federally sentenced Indigenous women.

Over the last 10 years, their numbers of incarceration have more than doubled.

Approximately 39 per cent of women incarcerated are now Indigenous, making them the fastest growing prison population in the country.

But what exactly is driving this mass over-incarceration of Indigenous people in Canada?

“There are a number of factors and they interact,” says Howard Sapers, the former Correctional Investigator of Canada. “You have to account for systemic discrimination and bias. That is a feature of the Canadian criminal justice system, sadly today.

“But it’s not the only factor and perhaps not even the biggest contributor, there are also historic reasons.”

Stopping or even reversing the over-incarceration of Indigenous people in Canada goes beyond the justice system.

There are numerous social issues, historical traumas, gaps in policy and root causes that have adversely impacted Indigenous people and communities for generations.

“Indigenous men and women carry a lot of disadvantage with them and they carry a lot of disadvantage that flows directly from colonial contact,” Sapers added. “So intergenerational trauma, the lingering effects of residential schools, of the 60s Scoop, of other policies around assimilation, the destruction of culture and language, breaking up families. These have lasting impacts.”

According to the office of the Correctional Investigator, Indigenous inmates are routinely classified as higher risk offenders and higher need in categories such as employment, community reintegration and family supports.

(Former prison watchdog, Howard Sapers explains some of the factors that have led to the over-representation of Indigenous people in Canadian prisons)

“Once you get that label of being high risk, it sticks with you. And that leads to more time in custody, fewer opportunities for conditional release, worst chances for successful reintegration. Which means higher recidivism and the whole cycle starts again.”

And the trend isn’t slowing down.

When Sapers was first appointed to the Office of the Correctional Investigator in 2004, the proportion of federally sentenced Indigenous men and women was around 17 per cent – by the time he left in 2016, it was 25 per cent, today it’s 27 per cent.

“This is in spite of criminal law amendments, Supreme Court judgments and a whole bunch of other social policy initiatives and it keeps on getting worse,” says Sapers. “And so there has been this reluctance to really engage and figure out root causes and what we have to do to stem the flow.”

Click here to read more about the growing disparity between Indigenous and non-Indigenous offenders

One man helping to stem that flow is Mark Marsolais-Nahwegahbow…

He is the founder of IndiGenius and Associates, an Ottawa-based First Nations-led Aboriginal justice consulting firm.

“These are communities that I work with, these are my communities and it’s really sad to see that the numbers are increasing,” says Marsolais-Nahwegahbow. “These institutions are the new residential schools.”

His firm specializes in the writing of Gladue Reports, a type of pre-sentencing report that examines the personal histories and backgrounds of Indigenous offenders to help courts determine a sentence.

“That report is a sacred story that needs to be respected, by the courts, by myself and everyone that it’s placed in front of,” he added. “And for some people, it’s the first time in their life that they’ve had that opportunity to share.”

In 1999, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that all reasonable alternatives to incarceration must be taken into account when dealing with Indigenous offenders.

But according to Marsolais-Nahwegahbow, many courts have failed to take the underlying principal seriously.

“Do I really feel that these Gladue reports are being used in case management within the provincial and federal systems? I don’t know what the percentage is but I don’t believe so,” he says. “Gladue is one area that is still being run by the western justice system and for some reason, they don’t let go.

“It needs to be given back so that we can control it and we can heal our people.”

There is also a shortage of experienced Gladue writers across the country – something that Marsolais-Nahwegahbow and his firm have been trying to address for years.

He has recently partnered with the Vancouver Community College in B.C. and is in the process of designing a curriculum for writing Gladue Reports.

It’s still in the early stages but he hopes one day to have it offered as a full-fledged course.

“We need more Gladue writers, we need expert Gladue writers,” he says. “It’s trying to set a national standard so there’s something to benchmark because the reports obviously in the court system are still being scrutinized.”

So where exactly does the federal government stand in all of this?

While the over-incarceration of Indigenous people in Canada has been well-documented for decades, changes to the criminal justice system have been slow and largely ineffective.

25-years ago, under the Corrections and Conditional Release Act, they recognized that the approach to corrections should be fundamentally different for Indigenous people.

A more restorative community-based approach to corrections was passed into law but has never been fully implemented.

It’s an issue that the current Correctional Investigator of Canada, Ivan Zinger, recently brought up in his annual report.

“These sections allow for the minister of Public Safety to enter into agreements with Indigenous communities for the care, custody or supervision of Indigenous people by Indigenous communities,” he said.

Currently, there are only nine such healing lodges in operation across the country. Five are operated solely by the Correctional Service of Canada while the others four are run by Indigenous communities.

But according to Zinger, the lodges are grossly underfunded, understaffed and there remains a large gap in funding between those run by the CSC and those that are operated by the communities.

“My issue is that there was a great opportunity 25 years ago to really do some great corrections and hand over some responsibilities back to Indigenous communities,” Zinger told APTN. “But it wasn’t embraced, it wasn’t done right. And I would hope that the Correctional Service of Canada and the Minister of Public Safety would actually look at this closely to improve the correctional outcome of Indigenous people.”

“For me the number one human rights issue in Canada – that the incarceration rate for Indigenous people keeps climbing year after year after year, relentlessly. Indigenous people are released much later in their sentences than non-Aboriginal, most of them at statutory release, which means that two-thirds of their sentence.

“They are in higher security typically, they’re more likely to be in segregation and then when they do go out, they’re more likely to be suspended or revoked.”

Public Safety Minister Ralph Goodale has welcomed Correctional Investigator’s Annual Report and responded in a written statement.

“To help address the over-representation of Indigenous Peoples in Canada’s criminal justice system, and to help those who have been incarcerated heal, rehabilitate and find good jobs, Budget 2017 invested $65.2 million over five years, starting in 2017-18, and $10.9 million per year thereafter.”

Click here to read Public Safety Minister Ralph Goodale’s full statement.

What about the federal Minister of Justice?

As part of her mandate, Jody Wilson-Raybould has been tasked with reforming the Canadian criminal justice system, specifically as it relates to the over-representation of Indigenous people incarcerated.

“I fundamentally believe that a measure of my success as the minister of Justice will be recognizing where those numbers are at the end of my mandate,” Wilson-Raybould told APTN. “And addressing the issues that have brought the vast majority of people into the criminal justice system, other than criminality.

“Looking at issues like addictions and mental health issues, looking at poverty, marginalization, looking at the legacy of colonialism for Indigenous peoples.”

While crimes rates have been on a steady decline over the last decade, the previous Conservative government’s “Tough on Crime” agenda had an adverse impact on Indigenous offenders.

One that saw harsher conditions of confinement, a focus on security as opposed to rehabilitation, mandatory minimum and longer sentences and fewer opportunities for conditional release and parole.

The Liberal government is in the process of reversing some of that legislation but progress has been slow.

“To move away from punishment and towards other measures of restorative justice, addressing delays in the criminal justice system and also ensuring that we’re looking at prevention,” Wilson-Raybould added. “And making a concerted effort that we provide the wrap-around services that are necessary through drug treatment courts and sentencing circles.

“That we provide the necessary off ramps for individuals, so hopefully the first time they find themselves in the criminal justice system will be the last time.”

It’s a tall order.

After 150 years of policies and laws meant to keep Indigenous people marginalized, changes to the system require a fundamental shift in the relationship between Canada and its first people.

(Independent Senator, Kim Pate addresses the failure of the government to deal with the over-incarceration of Indigenous people in Canada.)

“Our governments, provincial, territorial and federal have a responsibility to hold up the standard and demand that the standard of care, that’s available for individuals, is one that upholds our law. Not one that actually persistently keeps people down.”

But how do you change a system and a way of thinking that’s as old as the Canadian state itself?

For Dan Parlow, it was reconnecting with his culture – something that was denied to him throughout his life both in and out of prison.

“My life hasn’t been exactly perfect, I’ve had my falls along the way too,” Parlow says. “But it’s a journey right and being connected to the land, going to ceremonies, working with Elders and healing circles. So when that fall came I knew where to return for my healing. But it’s not like a light switch, after 30 years of incarceration, healing is a lifetime journey.”

After being released from prison in 2013, he began studying criminology at Ottawa’s Carleton University.

In between classes he also works as a research assistant with the hopes of one-day teaching and helping other former inmates reintegrated into society.

“I’m studying criminology in the hopes of being a part of the dismantling of this colonial justice system that is hurting our people,” Parlow says.

“And possibly one day returning back to the university and teaching criminology through an Indigenous lens. Working with what’s left of my life and helping others.”

But while Parlow was able to change his life for the better, he doesn’t deny that it’s still a daily struggle.

“We are continually healing and for the other Indigenous people incarcerated, I’d like to reach out to them and let them know that there is hope to return to those ceremonies, return to the Elders and their teachings.

“It’s not going to be an easy journey, it’s a long journey and it’s painful at times but it’s well worth it.”

We need intense trauma therapy, self worth, esteem and awareness building, goal setting, life skills education and a solid support foundation. None of these I can see the Canadian government doing so it’s on us to do it ourselves. Start with a small non profit org and grow from there. It’s possible. I’d happily be part of something like this.

Thank you to the creator of the Gladeau report who’s addressing the root of all, keep it up.

We need intense trauma therapy, self worth, esteem and awareness building, goal setting, life skills education and a solid support foundation. None of these I can see the Canadian government doing so it’s on us to do it ourselves. Start with a small non profit org and grow from there. It’s possible. I’d happily be part of something like this.

Thank you to the creator of the Gladeau report who’s addressing the root of all, keep it up.

Talk. Talk. Talk. That’s all it’s been for Rod Glode, now in his twenty-eighth year of consistent torture and abuse. I have written: Justin Trudeau, Ralph Goodale, my M.P., Don Head, and Howard Sapers , all multiple times. Nothing has changed for him. In fact, it’s worse. That he is being warehoused is not in doubt. There is proof of the abuse, both physical and mental. I have contacted every Native help source I could find. So far, no one has responded with any kind of help for Rod.

Talk. Talk. Talk. That’s all it’s been for Rod Glode, now in his twenty-eighth year of consistent torture and abuse. I have written: Justin Trudeau, Ralph Goodale, my M.P., Don Head, and Howard Sapers , all multiple times. Nothing has changed for him. In fact, it’s worse. That he is being warehoused is not in doubt. There is proof of the abuse, both physical and mental. I have contacted every Native help source I could find. So far, no one has responded with any kind of help for Rod.