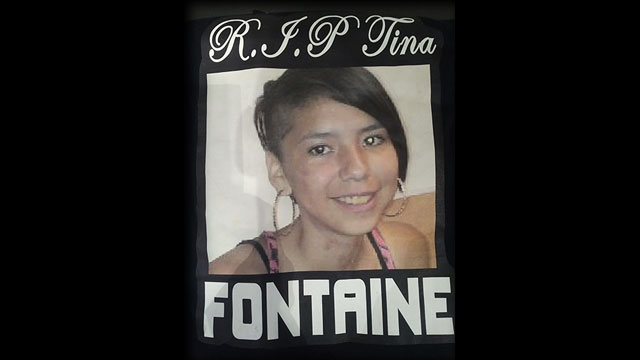

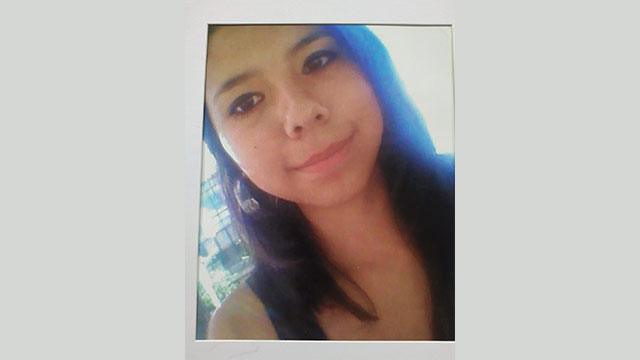

After Tina Fontaine: Exploitation in a Prairie City

Like many other stories we heard from survivors of sexual exploitation, some of them have had horrific childhoods, something that can largely impact their later years. Candace is another example of this.

This is the first time Candace is sharing her story. “Candace” is not her real name, we are protecting her identity.

Toss-away kid

Raised in a middle-class neighbourhood in a small Manitoba town, Candace said family life looked very normal on the outside. But inside her home lived a deep, dark secret.

Since she was a toddler, Candace was sexually exploited by her own mother for the pleasure of grown men.

“It always happened under her roof. She was the one who brought them in,” said Candace. “I remember I was the Hydro bill, I was the new pair of shoes, I was many things.”

It didn’t matter what day of the week it was, Candace was often sexually exploited in the evenings.

“Any orifice of my body was fair game,” said Candace, adding she was forced to give oral sex. Still to this day she has a very bad gag reflex because of that memory.

“I was living with a very cruel parent.”

At five years old, Candace remembers her mother sitting her down on her bed and telling her what a botched abortion was, telling Candace she fit that definition.

“I was so useable and such a toss-away kid to her,” said Candace.

Because her parents divorced when she was quite young, her biological father was not around.

Although the sexual exploitation stopped around the age of 11, after her mother married again and found financial security, the physical abuse did not.

“I was beat if I vacuumed the rug in the wrong direction,” said Candace. “It was not a safe place for a child.”

At age eight, Candace tried to commit suicide, the first of many attempts.

A social worker got involved in the family affairs, but Candace knew what was expected of her.

“She trained me so well to be such a good liar, and keep her secret, I didn’t say anything.”

“Even going to school you literally held on [to] your persona that very second you walked out your door.”

The Men

When she heard someone coming up the stairs at night, she says she knew what it meant.

“There wasn’t one face when you’re trafficked, you have multiple faces that are abusing you,” she said. “You are haunted with a blurred version of faces.”

She never remembers a brown face, she said, only Caucasian men in her bedroom.

She has no idea where her mother found these men, either.

While living in the city of Winnipeg for a brief time, Candace remembers one particular perpetrator she’s never been able to drive from her mind.

“I remember this one guy who was in the wheelchair, he had to pull himself up [the stairs], and to this day that is still the most terrifying sound,” said Candace.

“He was so cruel.”

Today Candace will not live in a house with stairs. It is too triggering for her.

Candace said she’s never confronted her mother over what happened.

“She will never take ownership for anything. I’ve never met another survivor where they said their offender has taken responsibility for it.”

Candace said she was proud of fellow Inuk Susan Aglukark for naming her perpetrator during a hearing of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls in Rankin Inlet, Nunavut in mid-February.

Story here: Inuk singer Susan Aglukark outs her childhood abuse

“I think of someone as strong as Susan Aglukark, she named her offender, finally.”

Her catalyst

At 16 years old, Candace finally left the family home. As a young adult, she started to experiment with drinking but for the most part, she said she just “ate her feelings.”

“When you’re trafficked like that, people pick up how easy you are to use. You’re very pliable, you’re very usable, and you go along with it.”

In her early adulthood, she suffered abusive relationships with various partners. She also struggled with trusting people or accepting love and kindness from others.

“To this day, my whole goal is to overcome these fears that have become my norm.”

She doesn’t understand how her mother could do this to her, calling it unjustifiable.

“How these monsters keep you from saying anything is they make everyone around you seem more scary than themselves,” said Candace.

“What I’m noticing now is that it’s people who have a sense of power that are able to get away with this [exploitation].”

She believes that not talking about who the predators are and holding them to account is what is taking the lives of young Indigenous people today.

Growing up she always heard the saying, “now is not the right time to talk about things.”

“That time and place bullshit just about killed me,” said Candace. “Everywhere is the right time, every place is the right place to talk about known perpetrators.”

Today she is grateful for the strong women who entered her life every so often.

“Most of us didn’t have strong women weave in and out of our lives. I did,” said Candace. “I’ll never understand how I got lucky.”

When Tina Fontaine was pulled from the Red River in August 2014, Candace said that was her final straw.

“It was Tina Fontaine that woke me up. I thought that could have been me, my daughter,” she said. “Tina Fontaine was my catalyst.”

Today Candace is that shoulder to cry on for other women and girls who are now sharing their stories with her.

“There’s gotta be voices that are saying, it’s okay to walk away from your parents, it’s ok to go find a safe number to call.”

“I just want to see these girls and boys [and] young women and men have a feeling of safety.”

Thank you APTN for sharing, and Candace for surviving! Your truth is a light of hope to those who are living in the dark.

Thank you APTN for sharing, and Candace for surviving! Your truth is a light of hope to those who are living in the dark.

I am humbled and uplifted by your bravery.

I am humbled and uplifted by your bravery.

Thank you for sharing and Thank You for your bravery! You are making a difference!

Thank you for sharing and Thank You for your bravery! You are making a difference!