The Blood Tribe, the largest First Nation in Canada says its using lessons learned from the opioid crisis to guide its response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Look, we’ve been through this before, it’s about saving lives,” said Coun. Lance Tailfeathers of the Blood Tribe, also known as Kainai Nation located in southern Alberta.

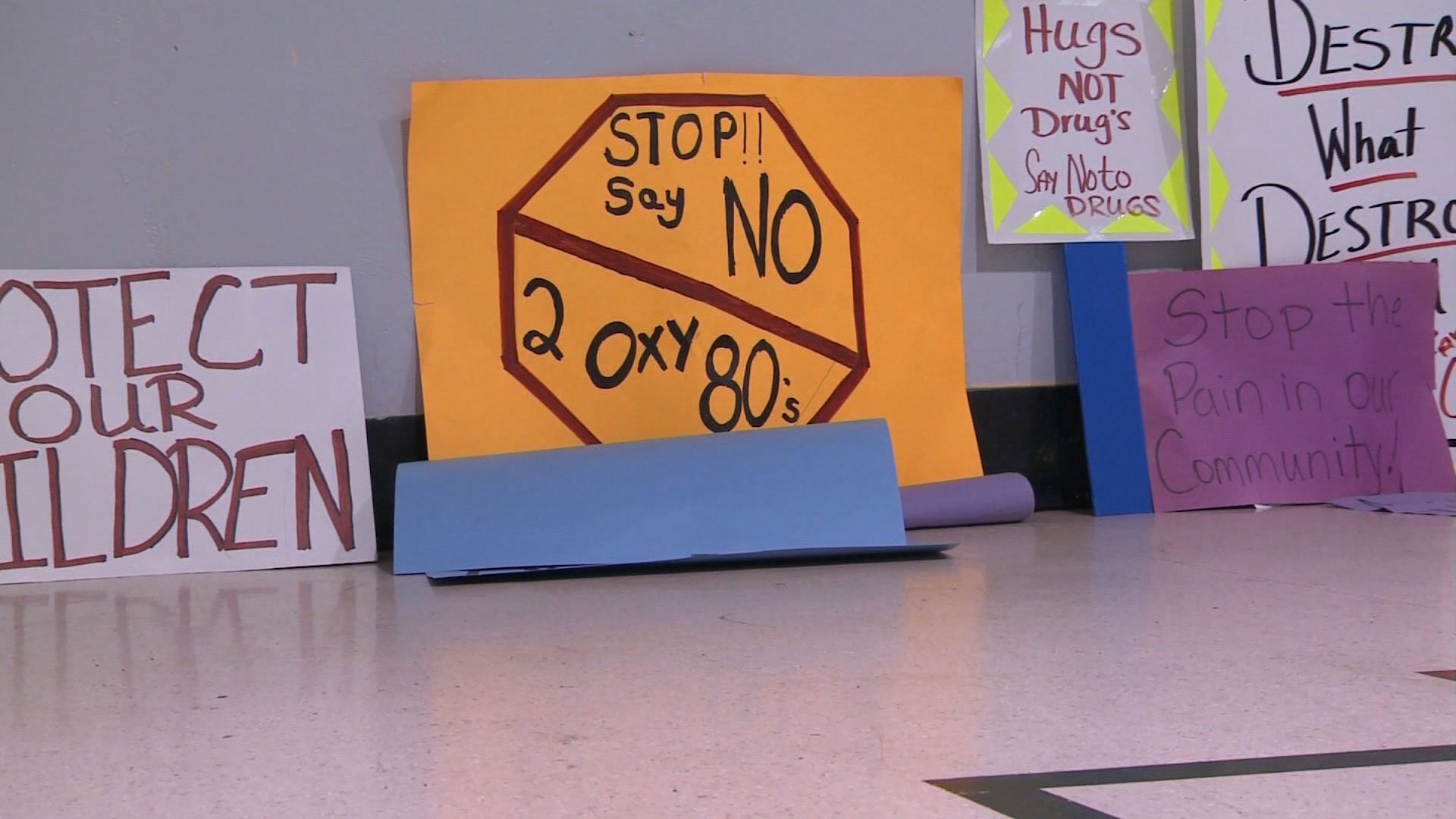

“Back in 2015, we had the opioid crisis and lost 20 members in two weeks due to overdoses.”

At its height, the drug crisis killed thousands of Canadians, caused hundreds of overdoses and claimed 34 lives on the reserve.

By comparison, COVID-19 has so far infected 14 Blood Tribe members and not caused any fatalities in the community two hours south of Calgary.

Wednesday was the first time in many days no new cases were reported.

About two-thirds of its 14,000 members live on reserve, said Tailfeathers, who was also a band councillor during the drug crisis.

“We were anticipating this after seeing how opioids infected the community. We already had the system in place – a sort of formula – to help one another.”

Three of the COVID-19 patients have recovered and the remainder are quarantined at a hotel in nearby Cardston, Alta., where the band is leasing rooms.

It has tested hundreds of members at its health centre and by using the mobile testing unit it first put into play during the opioid plague.

“When people are scared and worried we go to them,” Tailfeathers said, adding the band council is meeting twice a week, sending out regular bulletins and sharing answers to frequently asked questions as part of its state of emergency.

“It’s about making the community aware and being proactive.”

The first case of novel coronavirus was diagnosed in a band member infected on the job at a nearby Fort MacLeod horse meat factory.

Two other meat plants in Alberta have seen outbreaks – as have other First Nations in the province.

Read More:

‘It’s time to quit’: Blood Tribe hit with 21 drug overdoses in 5 days

The reserve is operating under a daily 9 p.m. to 6 a.m. curfew, closing its convenience stores and gas bars at 8 p.m., and observing travel restrictions.

“We don’t have checkpoints,” Tailfeathers noted, “but our tribal police have been very active.”

As he said, they’ve been through this before. And even before that.

“My mother remembered that during the tuberculosis (epidemic) in the 1950s and ‘60s people were confined to their beds. They weren’t allowed to leave the reserve and were locked down for several months.”