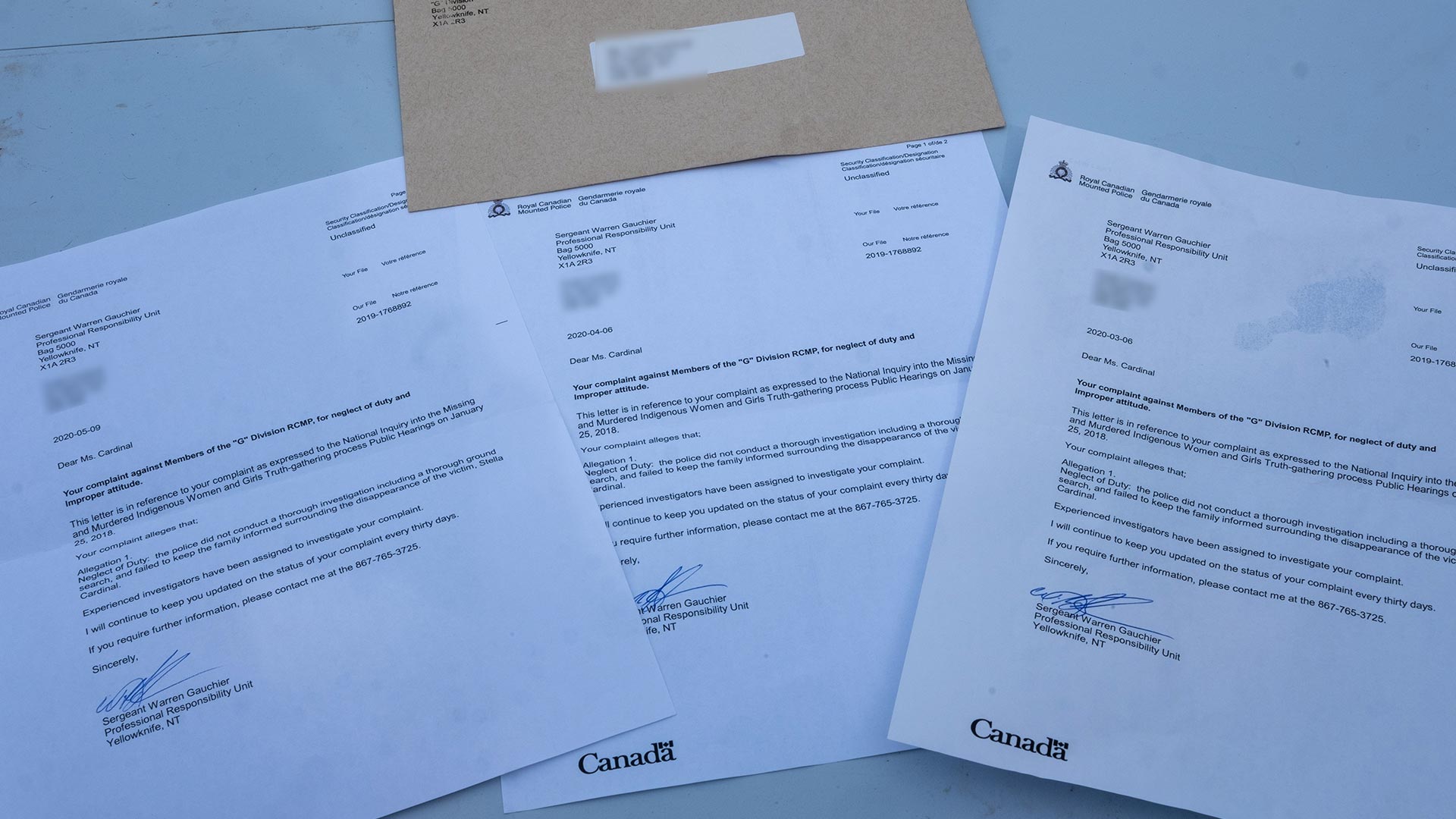

Every month Freda Cardinal receives the same letter from the RCMP and relives the painful questions surrounding the disappearance of her sister, Stella Cardinal.

The letters signed from the RCMP G Division are carbon copies.

A single page that states police are investigating “criticisms” Freda made against them in her testimony before the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls in Yellowknife in January 2018.

“All I have heard from the RCMP is that they would keep me updated,” said Freda. “Every letter they sent me says the same thing, over and over again. There’s no real updates.”

Her sister disappeared in the summer of 1970, when she was 19 years old. She was last seen at a remote fire lookout tower near Fort Smith, N.W.T.

Freda spoke her truth publicly at the hearings and alleged the RCMP neglected to act on various leads in the disappearance of her sister

At the time of the inquiry, there were 71 unsolved historical cases of missing and murdered persons in the Northwest Territories with 63 cases considered open.

At the inquiry, Freda made the recommendation that a dedicated task force be developed to handle these cases.

Her calls were answered, or so she thought.

In February 2018, the territorial government budgeted $304,000 for the RCMP unit.

A year later APTN News learned that a two-person RCMP unit was staffed to investigate the cold case files but no other information was ever provided.

APTN has made numerous requests for information and interviews that have been declined each time.

Ahead of the one-year anniversary of Reclaiming Power and Place: The Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, APTN again asked for an update on the progress of the historical case unit and how many families the RCMP had worked with so far.

“The Historical Case Unit values the work of the media and plans to eventually release information on some specific files to engage the public and support their investigative work,” said Julie Plourde, media relations officer for Yellowknife RCMP in a statement to APTN’s request for information. “However, the unit has not reached this point.”

It has taken decades for Freda to fill in the gaps of information on her sister’s case.

It wasn’t until she worked with the inquiry’s Family Information Liaison Unit (FILU) that she learned what investigators had done over the years.

“When FILU assisted me in going to the RCMP, they [RCMP] showed me a two-page, double-sided document. That was all they [RCMP] had done over the years for my sister’s file,” Freda said.

This left her with more questions than answers, like why an investigator went to the site in the wintertime where Stella was last seen a decade ago and what came of the trip?

Freda was disappointed in the federal government’s delay of an action plan illustrating how the inquiry’s 231 recommendations or calls for justice would be implemented.

“It just sends the message that the federal government is trying to make us happy saying they are doing something for us,” she said. “We need a holistic report for everyone who testified. I’m not surprised if some people have PTSD because of the inquiry.”

Freda is not alone with her frustration.

Lesa Semmler, an MLA for Inuvik Twin Lakes in N.W.T., said she was insulted the inaction was being blamed on delays related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

“They’ve had 10 months since they received the report; it’s not as if they have not heard the requests again and again,” Semmler told the legislature.

Semmler called on the territory to lobby Canada to release the action plan and, in the meantime, to develop an action plan of its own.

A teary-eyed Semmler spoke to the assembly not only as a politician but as an Indigenous woman, as a mother, and as an aunt of Indigenous women and girls, she said.

“We cannot have any more blood on our hands, lose any more loved ones. We can’t afford any more delays when it comes to the safety and protection of our women and girls and to us LGBTQ2IA people,” she said.

Semmler was one of the first to testify at the inquiry in Yellowknife, sharing the story of her mother, Joy Semmler.

She was only eight years old when her mother was murdered by a common-law partner in 1985.

According to Statistics Canada’s 2019 findings, the N.W.T. has the second-highest rate of violence against women in the country.

Freda said aftercare for families experiencing violence and those who testified should be a top priority of all levels of government.

At the time of the inquiry, she said she turned down counselling because of work commitments.

“I’ve gone to sweat (lodge ceremonies) on my own and that really helped me a lot, but we need more, more support. More than ever for telling our story. For those of us who did, we need help,” Freda said.

As the 69 families who testified at the inquiry wait for an action plan, the quest for answers for those like Freda will not be put on hold.

“I will never give up. I love my sister, Stella. Canada and the world needs to know what happened with our missing and murdered,” she said.