Two plaintiffs in the First Nations child welfare class action hope the landmark proposed settlement ensures other families don’t have to suffer the same tribulations they did.

Canada agreed in principle on Dec. 31 to two deals worth roughly $20 billion each to compensate victims of a racist, underfunded system and pay for its long-term reform.

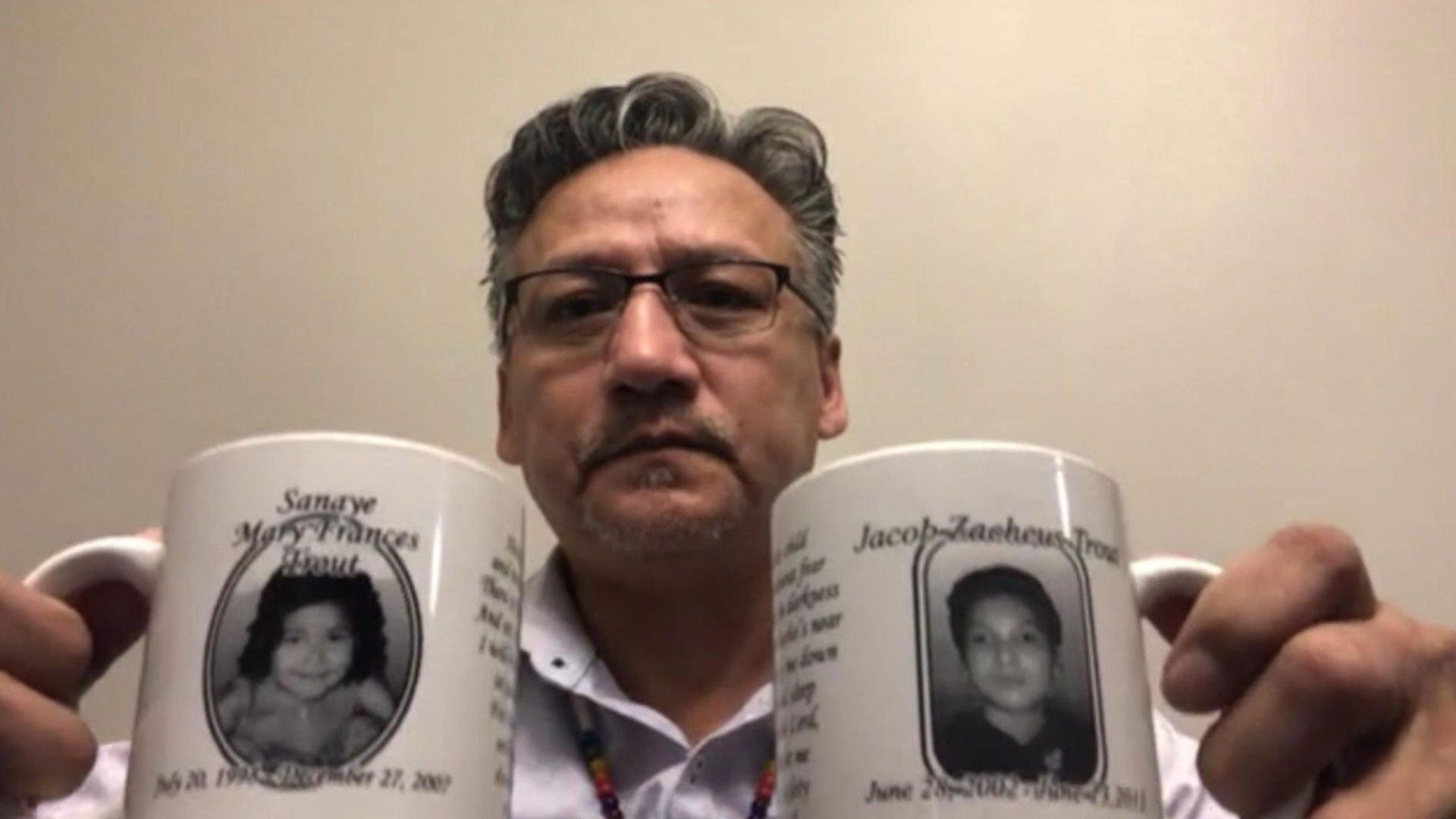

“It will not ease all the pain and the trauma we incurred. That’s for sure,” reflected lead plaintiff Zach Trout on Nation to Nation. “Because we’re still living through that trauma.”

The Cree father from Cross Lake First Nation in Manitoba says communities still need better access to essential programs and services so other families don’t have to struggle.

“That’s the reason why I took a stand, because I still see children that are still suffering today, which they shouldn’t be,” he said. “I wasn’t in it for myself or anything else like that. I was in it to try to improve the lives of our children.”

Two of Trout and his wife Veronica’s six children had Batten disease, a rare genetic disorder that begins in childhood and causes severe cognitive impairment.

Sanaye and Jacob were born in 1998 and 2002 respectively. Both died from their condition before age 10. Their parents cared for them round the clock for 13 years.

The children’s suffering was exacerbated because the things they needed weren’t available on the First Nation, Trout told N2N.

They were caught in a jurisdictional dispute similar to young Jordan River Anderson, a Cree boy from Manitoba who died in hospital at age five while the province and Ottawa squabbled over who would pay for his home care.

Trout’s statement of claim alleges Canada has known since at least 1981 these jurisdictional disputes were hurting people because that’s when a House of Commons special committee concluded the situation “leaves the Indians themselves confused since they are frequently left without any services while the two Governments are arguing.”

In class-action lawsuits, one person comes forward to represent a group of claimants, and so the inclusion or exclusion of people numbering potentially in the thousands was at stake with Trout’s claim.

At first, Ottawa wanted to fight him in court. The federal government argued it wasn’t liable because Jordan’s Principle, which the House adopted in 2007 to stop these disputes, didn’t exist yet.

But when he heard Canada changed its mind — that children who didn’t receive or were delayed receiving an essential public service or product between 1991 and 2007 would be eligible for compensation — he was overwhelmed.

“I was kind of surprised, because I was ready to go into a battle with this,” Trout said. “I wanted to take a stand for the children that are going through the same suffering in our First Nations community.”

Canada has been fighting legal battles over First Nations child welfare for nearly 15 years.

That’s why skepticism was the first thing that went through Jonavon Meawasige’s mind when he heard about the proposed agreements.

“I’m a little bit skeptical about where the government could still change their minds on the deal. But other than that, I’m happy,” said Meawasige. “I’m happy for the children that will benefit from this decision that Canada made.”

Meawasige, a lobster fisherman from Pictou Landing First Nation in Nova Scotia, is the appointed legal guardian for his brother Jeremy.

Jeremy has multiple disabilities and is the lead plaintiff for children denied services after 2007.

Even once Jordan’s Principle came into existence, Canada was so stingy and strict about it that years later an $11-million fund set up for the program had never been accessed.

Jeremy and Jonavon’s mom Maurina Beadle sued Canada in 2012 because of its narrow approach — and won.

Beadle fought fiercely for Jeremy’s rights, but the family nevertheless went through a lot of pain, suffering and hardship.

“There was a lot of times where we didn’t know where the money was going to come from. A lot of the time we struggled to even keep things on the table for the three of us,” Jonavon said. “It was always just the three of us growing up.

“Hopefully this benefits more children, and keeps children home with their families.”

That’s the other part of the proposed settlement. Children scooped from their homes on reserves and in the Yukon between 1991 — which was when the discriminatory child welfare funding policy came into force — and spring 2022 are expected to receive at least $40,000 each.

But how much money people like Jeremy, Jonavon and the Trout family will get hasn’t been negotiated yet.

Jonavon said the compensation would provide for important upgrades Jeremy needs to keep him where he belongs — in his community.

“He would get the extra things that he would need to stay at home.”