Cara McKenna

APTN National News

The Stó:lō people are named in their language after the Fraser River, which is the community’s lifeblood and flows through their picturesque territory southeast of Vancouver, B.C.

Just a few generations ago, dozens of people spoke the nation’s language of Upriver Halkomelem.

But in the last decade, almost all fluent speakers have died.

There is just one elder left who early in life had to fight to keep her language, and is now trying to pass it on before it’s too late.

The Knowledge Holder

I try my best not to lose [my language], because I can’t have a conversation.”

– Elizabeth Phillips, Stó:lō elder

When Elizabeth Phillips was a child, she was put into St. Mary’s Indian Residential School in Mission. She was forbidden to speak the language that both of her parents spoke to her as a baby.

Phillips was a loner at the school and supervising nuns became concerned that she wasn’t associating with other children enough.

While other children played, she would stand alone at the outside gate, staring out at the Fraser River and thinking in her language.

“And I guess that’s what saved me,” she says now, sitting outside her home in the Fraser Valley.

Phillips’s small red house stands in stark contrast to rolling green hills and clear blue sky. Nearby is the Fraser.

Inside, three linguists from the University of British Columbia are bustling around her kitchen and setting up an array of ultrasound equipment as Phillips observes the elaborate set up.

Phillips laughs good-heartedly when one of the linguists explains that she’ll need to put some goopy ultrasound gel under her chin.

It might be the first time anyone has done an ultrasound on her mouth, but the experience of being recorded by academics is not a new one for Phillips.

At 77, she’s the last known fluent speaker of the Stó:lō Nation’s Upriver Halkomelem language (also called Halq’eméylem) – a Salish dialect that’s related to two other Halkomelem dialects, but distinct to the Stó:lō people.

Above: Phillips speaks the phrase “simple language for beginners” in Upriver Halkomelem

It seems like yesterday to Phillips that a group of Stó:lō elders would gather to speak Upriver Halkomelem and record what they knew in a dictionary. It was a time when she could have long conversations on the phone with friends without speaking a word of English.

But those elders’ deaths came in rapid succession – more than 20 in the last two decades.

Those elders were all a decade or two older than Phillips, who was always the youngest one in language groups, but she got invited to attend before she was an elder because of her unique ability to speak fluently even after residential school.

Several years ago, an elder named Elizabeth Herrling who was working to record the language in stories died at 93, which is when Phillips stepped up her work to record it.

Above: a torch lighting story told by Herrling

Sadly, Phillips is now left with no one to have real conversations with, but she still thinks in Halkomelem and communicates as much as she can with speakers who are learning, including her daughter Vivian.

“I try my best not to lose it, because I can’t have conversation,” she says.

“But I text in Halkomelem.”

Phillips pauses, then bursts into laughter at the notion.

“The phone is always trying to correct me!”

Preservation

Most of the languages probably are going to come to a place where people aren’t speaking them fluently.”

– Strang Burton, linguist

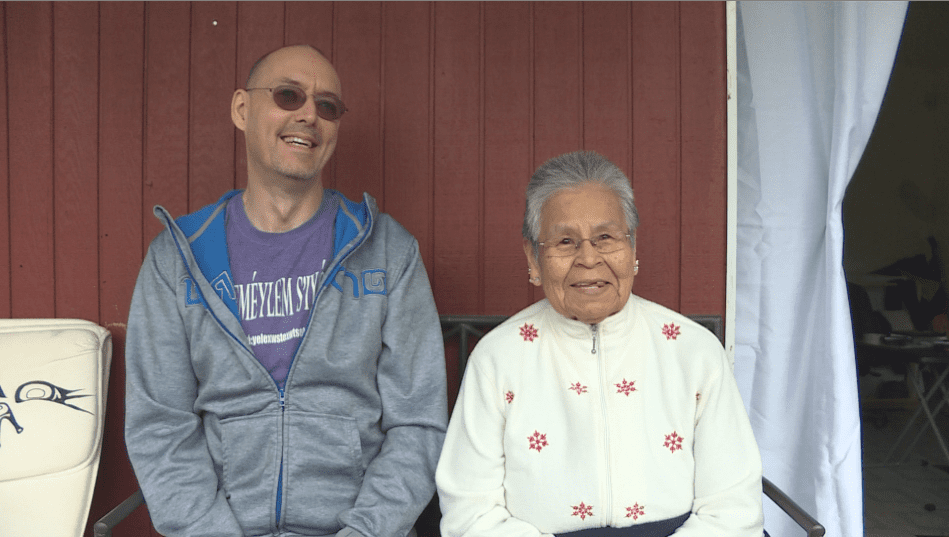

Joining in on her laughter is Strang Burton, who works for the Sto:lo Shxweli language program and UBC’s linguistics department.

Phillips and Burton have been working together for nearly two decades and they switch easily between having serious, quiet conversations and laughing jovially together. Burton calls her “Siem,” a Halkomelem word that, in English, loosely means “respected one.”

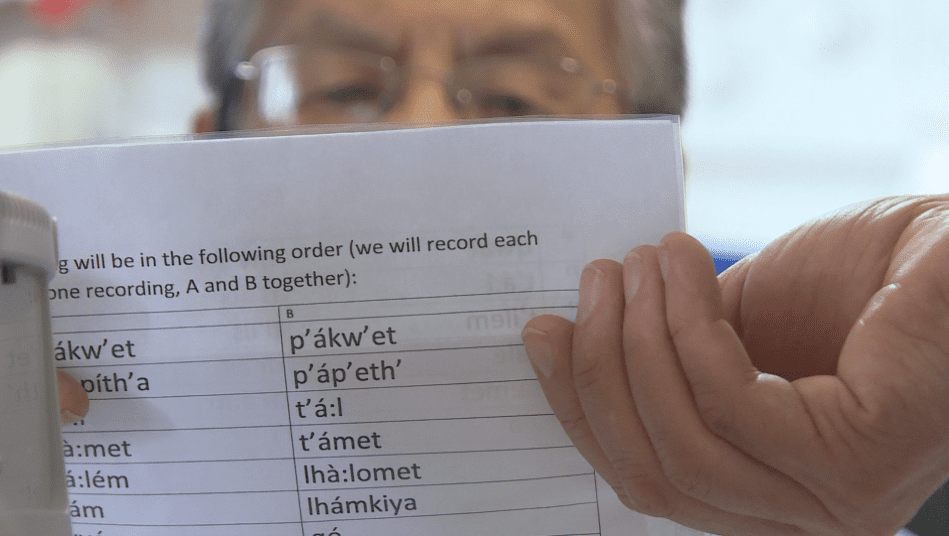

Together, they’ve recorded many stories and other language material. Burton got the idea to do a language ultrasound on Phillips when he saw other linguists using the equipment on Mandarin and Japanese.

“I thought, well, let’s do it for Halkomelem, because people were having trouble with the sounds of Halkomelem,” he says.

Burton believes it to be the first time the technology has ever been used on an Indigenous language in Canada.

He said he hopes it will allow people who are teaching the language in local schools to improve their pronunciation of the language, which is notoriously tricky.

He plans to impose the ultrasound images with external videos he’s taking of Phillips’s mouth so that others can see how her mouth and tongue move as she’s speaking.

But, after decades of work, Burton is realistic about the prospects of a severely endangered language like Upriver Halkomelem truly being saved.

“Most of the languages probably are going to come into a situation where people aren’t speaking them fluently,” he says.

Time is Ticking

“For people to become really fluent again, that requires something social to happen.”

– Strang Burton

The reality in British Columbia is a bleak one – the province is home to more than half of Canada’s 60-odd Aboriginal languages, and almost all of them are in danger of disappearing.

The languages are a crucial part of culture, ceremony and connection. Many Indigenous words can’t be translated accurately into English.

In the Canadian Liberal government’s first federal budget earlier this year, it was announced that $5 million per year would be siphoned into supporting the country’s Indigenous languages, in comparison to more than $2 billion for French.

“Considering the number of First Nations languages there are in Canada, it’s not a lot,” Burton says.

“If there were just one First Nations language in Canada, I guess that would be a lot.”

More funding is certainly needed to continue crucial work to preserve languages, but Burton says, more than that, fluent speakers like Phillips are needed to pass the languages along. And they’re dying off at a worrisome rate.

“For people to become really fluent again, that requires something social to happen,” Burton says.

“Which is happening maybe a little bit.”

But the small changes are not enough. Burton says, what is realistic, is that people can experience the language through stories about people’s lives and traditional practices. That’s what he’s trying to do through his current work with Phillips and previous work with other elders.

“Without a Native speaker to go to for subtle translations and things, you’re never going to be sure you’ve got it exactly right,” he says.

“But with the resources we have, probably if people get together and they want to speak, there’s enough stuff that they could access in the archives to help them have a real conversation.”

Burton believes the community is positive, and he has seen many children learning the language through school programs, which is hopeful to Phillips.

Many years ago, before Phillips’s own mother passed away, she asked her daughter Vivian to live with her, which has helped her to become proficient in the language and pass it down to her own children.

“That’s quite an honour because that was so forbidden, you know,” she says.

“A lot of our people were punished because they spoke their language.”

It’s a painful subject to breach, and Phillips gets distracted mid-thought when she notices an eagle flying above her. She smiles at the reminder of strength and power.

“They always seem to know what’s going on,” she says.

@CaraMcK