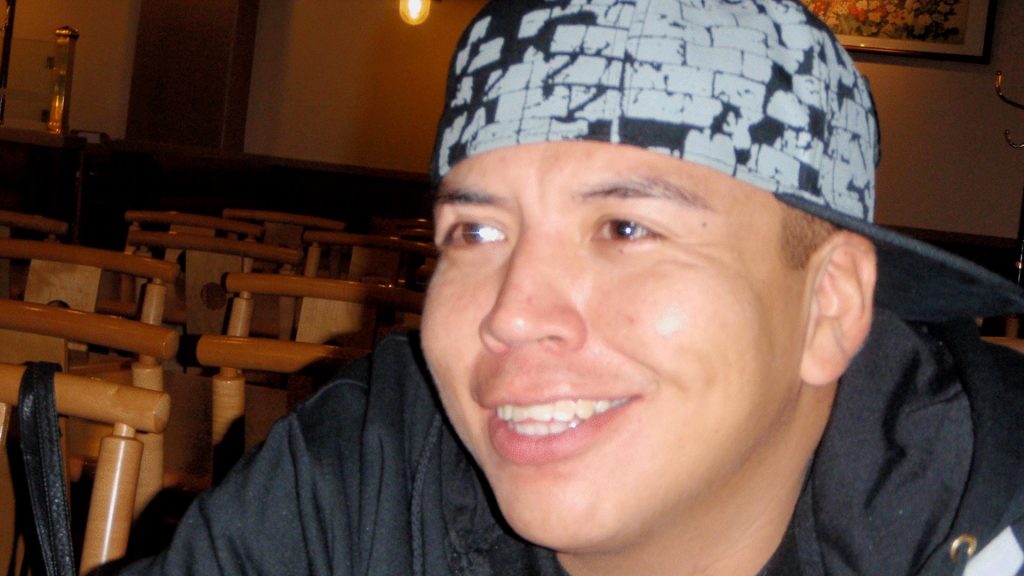

Dale Culver died in 2018 after being arrested by Prince George RCMP.

Family members of Dale Culver who died after being arrested close to six years ago, expect to wait many more before learning if five RCMP officers will be convicted of manslaughter and obstruction in the case.

The family “remains unwavering” in its search for justice, despite the wait, said a statement released Thursday by the B.C. Civil Liberties Association.

“We want the public to know how difficult it has been for us since my dad was killed,” said Lily Speed-Namox, Culver’s eldest daughter.

“We have been in the dark throughout much of this process.”

The case is highlighting delays in the civilian oversight process, while renewing debate about whether police body cameras would enhance transparency and accountability.

The chief civilian director of B.C.’s Independent Investigations Office, Ronald MacDonald, addressed the delay in a statement, calling it “unacceptable and unfair.”

Read More:

Families of men who died in RCMP custody still searching for answers

But the IIO’s investigation into Culver’s death was “exceptionally complex” and “extraordinarily demanding in terms of resources,” said MacDonald. He said the office has been hindered in attracting and retaining investigators as he renewed calls for greater funding and changes to its compensation model.

“Without changes, there can be no reasonable expectation that the IIO will be able to continue delivering fair and thorough investigations to the standard required in a timely fashion,” he said, adding that “passion for justice only gets one so far.”

Culver, from the Gitxsan and Wet’suwet’en Nations, was arrested in Prince George on July 18, 2017, after police were called about a man allegedly casing vehicles.

The independent office that investigated the case said the 35-year-old was pepper-sprayed during a struggle, had trouble breathing and died in custody.

The civil liberties association said although the independent review in 2019 found “reasonable grounds” to believe two officers may have committed offences related to use of force, and three others may have obstructed justice, the Crown was not handed a final report until 2020, and charge approval took nearly three more years.

Culver’s family said the delay has been too long and his aunt, Virginia Pierre, said relatives “cannot shake off the devastation until justice is done.”

Constables Paul Ste-Marie and Jean Monette have been charged with manslaughter, while Sgt. Jon Eusebio Cruz and constables Arthur Dalman and Clarence MacDonald are accused of attempting to obstruct justice, the BC Prosecution Service said Wednesday.

“It happens way too much. Too many have died in the hands of the RCMP. The police are supposed to protect us, not kill us,” Pierre said in the statement.

Debbie Pierre, Culver’s next of kin, said his youngest child was less than six months old at the time of his death and will be turning six in a few weeks.

“We hear that there may be a court hearing by mid-March related to the charges, and we know that it may take many more years before any court decisions are made,” she said.

The First Nations Leadership Council also issued a statement Thursday, saying it supports the charges and stands with Culver’s family and communities.

Regional Chief Terry Teegee of the B.C. Assembly of First Nations said the charges were a “positive step” toward a national effort to ensure Indigenous and racialized people in Canada “are not subject to the discrimination and injustice that is so deeply inherent in the justice system.”

Grand Chief Stewart Phillip with the Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs said he was “relieved” by the charges, adding that “investigations into RCMP conduct, including police-involved deaths, are taking far too long.”

Roughly six months after Culver’s death, the BC Civil Liberties Association wrote to the chairperson of the civilian review and complaints commission for the RCMP, saying it was aware of reports from eyewitnesses that Culver “was taken forcibly to the ground by RCMP members immediately after exiting a liquor store, apparently unprovoked.”

The letter also raised what it called “troubling allegations” that RCMP members told witnesses to delete any cellphone video.

“This would provide a strong basis on which to question the accuracy of certain RCMP members’ statements to investigators and notes, as well as RCMP public statements,” the association said.

Brian Sauve, president of the National Police Federation, said in a statement Wednesday that in-custody deaths are rare and tragic and the nearly six-year wait for charges was “unacceptable” for Culver’s family and the officers involved.

Plans to deploy body-worn cameras across the country would help protect police and the public, providing transparency, evidence and accountability, he said.

In an interview, Sauve said he included the nod to body-worn cameras because of allegations that officers told civilians to delete video of the 2017 incident.

“Should these members have been outfitted with body-worn cameras, then, obviously, you have a piece of evidence there,” he said Thursday.

That evidence could have helped a more timely conclusion being reached about whether an offence had been committed, he said.

“A body-worn camera is not the panacea with respect to solving any problems that the public might see. It is just one more tool for gathering evidence,” Sauve added, noting police services are divided over their use.

Meghan McDermott, a lawyer and the policy director of the B.C. Civil Liberties Association, said body-worn cameras are often a top priority for people whose loved ones have died in interactions with police, as they seek insight into a person’s “last moments.”

However, McDermott said she’s “very skeptical” of body-worn cameras.

The association has raised concerns about privacy and it advocates for certain requirements if cameras are used, such as clear disciplinary measures for officers who violate rules for wearing them.

The province’s guidelines for body-worn cameras are not clear about the extent to which it’s up to individual officers to turn them on and off, McDermott said.

The standards state “indiscriminate” or continuous use of the cameras is not permitted, and police departments must enact policies ensuring officers activate their camera “as soon as it is safe and practicable to do so” when responding to an incident involving aggressive behaviour or use of force.

Before placing stock in cameras, McDermott said the government should strengthen rules around how police interact with the public.

“They shouldn’t have so much discretion, that’s just a key thing that we say over and over again,” she said. “Their discretion should be shaped more by our solicitor general and our politicians, so that then things don’t happen like (Culver’s death), and then we have to rely on the accountability mechanisms to clean it up.”