Natteal Battiste sits on the edge of the boxing ring, wraps her hands, and pulls on her red and black gloves.

She considers the Mi’kmaw-run Tribal Boxing Gym in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, a sanctuary. Boxing is more than a workout for Natteal, who faces racism in different ways as a Mi’kmaw and Black woman from the Acadia First Nation.

APTN Investigates: Racism Lives Here Too – Watch part 2 here.

“I was just running into situations where I had to really defend myself, whether it was, I’m walking in a party and someone just randomly yelled out the n-word to me. And the next thing we know, that person’s coming at me and we’re having a full-blown fight,” said Natteal.

“It always came down to — I was either the girl from the reserve or I was the girl at the party that was Black.”

Like everyone else around the world, Natteal watched on May 25, 2020 as a Minneapolis police officer kneeled on George Floyd’s neck for eight minutes and 46 seconds, killing him. She watched Black Lives Matter rallies unfold, far away and at home in Nova Scotia.

“Half the battle is to have people who are finally caring about Black Lives Matter and people who are finally caring about missing and murdered Indigenous women,” said Natteal.

“But that’s just a headline to them. And once it’s out of sight, it’s out of mind.”

Natteal says her identity as Black and Mi’kmaw woman isn’t a weight to carry, but a source of strength.

“All my ancestors are survivors and they’re all warriors because I’m here.”

‘I didn’t know the connection was so strong’

Mi’kmaw and Black people in Nova Scotia have survived a history of racism as old as colonization, stretching back over 400 years.

“There’s so much history here, but you’re just not taught it,” said Natteal.

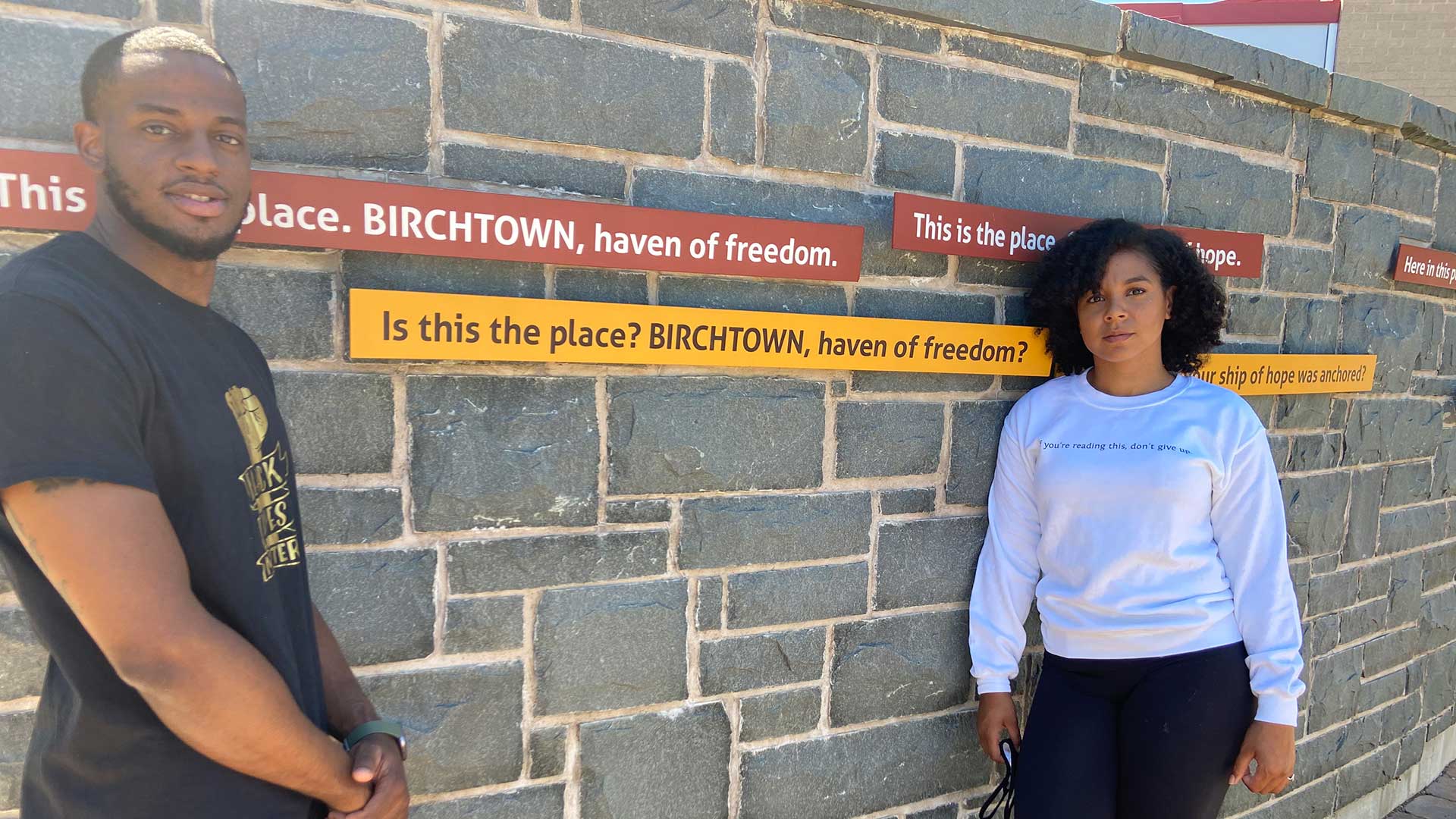

On a warm sunny morning in late August, Natteal and her partner Robert Downey, move quietly through a guided tour of the Black Loyalist Heritage Centre in Birchtown, 200 km southwest of Halifax.

The Black Loyalists were former slaves, promised freedom and land by the British if they fought in the American Revolutionary War.

More than 3,000 Black Loyalists arrived in Nova Scotia starting in 1783, their names recorded in the Book of Negroes and etched on the windows and floor of the heritage centre.

But promises were broken and inequality persisted. Tensions soon erupted and this is the site of the first recorded race riots in North America.

“I’m still blown away by that,” said Robert. “Like, I’m just trying to think of all the violence and all the things that happened. And I’m right here. I’m just trying to picture the race riots as I’m walking.”

And slavery still existed. At the same time the Black Loyalists arrived, over 1,200 slaves were brought to Nova Scotia with an influx of white settlers.

It’s a history lesson Natteal and Robert never got in school; one that’s both eye-opening and emotional.

“I wanted to cry so many times,” said Natteal. “I was seeing what life was like in their shoes and how damaging that was to the generations to come.”

“Because it’s a lot of triggers, right?” said Robert. “You connect with all these things that’ve happened. And then it hits home, ‘cause you’re here. Nova Scotia is my home.”

Tour guide Jason Farmer lead Battiste and Downey through the Black Loyalist site, on a journey from slavery to life after the promise of freedom.

“The Mi’kmaq would help the Black Loyalist with knowledge, including what to hunt and fish in this area and others areas throughout Nova Scotia,” said Farmer.

Robert Downey is from North Preston, the largest black community, settled long before Canada was a country.

“And for me, it was a wow factor walking in the door,” he said. “I needed to see that my ancestors were taught how to survive. I never knew of the Black and Native relationship at all.

“I didn’t know the connection was so strong, so long and deep.”

‘We all feel there is a connection’

A few weeks later, Robert and Natteal drive the winding road into the rural community where he grew up, where his family still lives; taking the history lesson back home to North Preston.

“My very first time going to North Preston, I was being told all the negative stuff,” said Natteal. “But really, my first drive up there, I was just like, well, this this is a reserve. They’re living the same type of struggle.”

Robert has great memories of growing up here, in a large extended family.

“You can find someone in each house that you know,” he said. “You felt safe.”

It’s a sharp contrast to the stigma attached to the community, painting it as a dangerous place. And to the reality of racism Robert faces outside the community.

“You start to run into racism, stereotypes,” said Robert. “My last name for example is smeared all over Google in the most negative way. Just the Downey name in terms of people who have been involved in criminal activity.

“It’s hard to even present a resume for a job that says Robert Downey from North Preston because of the history behind the last name of Downey.”

North Preston was settled in the early 1800s. Black Loyalists were joined by other waves of Black migration escaping slavery, including the Jamaican Maroons, and the refuges from the War of 1812.

It’s just one of over 50 historic African Nova Scotian communities.

“When I first met my boyfriend’s grandmother. She was like, ‘oh, you’re Native,’ and right there, it was a history lesson,” said Natteal. “She was like, ‘I want you to know that when our family first moved here, it was the Natives that helped us.’

“And it was like I appreciated her in that moment because she connected me to the history of the land.”

“We all feel there is a connection,” said Micah Smith, a business owner, musician, and social activist, from North Preston.

“When we arrived back then, this area was called the Barrens. There was nothing,” said Micah. “We were put back here in the winter. So, the Natives, they helped us survive.”

Micah is Robert’s cousin. They Robert meets up outside the Saint Thomas Baptist Church, the heart of the community.

Like Robert, she’s had trouble getting a job when she puts her North Preston address on the application. She recounts stories of being pulled over in police street checks.

In 2019, the Halifax Police Chief apologized for street checks that target the Black community. Last month, Nova Scotia Premier Stephen McNeil apologized for systemic racism and created a design team to tackle changes in the way the justice system deals with Black and Indigenous people.

“Apologies mean nothing,” said Micah. “In 2020, we want changed behavior.”

A big goal for Micah — to change the perception of African Nova Scotian communities.

“I need people to understand that we’ve been here longer than Canada was Canada,” she said. “We built the country. We need more respect than we get.

“And I would like everyone to know there is no place like North Preston. The spirit of the community is alive and well. It’s an amazing place.”