Her death shook the nation.

The country was told how we failed her, how we all could have done better.

The photo struck a jarring blow to Canada’s image: the Winnipeg Police Service Underwater Search and Recovery Unit holding up a blue tarp as they recovered the body of Tina Fontaine from the Red River in Winnipeg on August 17, 2014.

(Tina Fontaine’s body was pulled out of Winnipeg’s Red River on August 17, 2014. Photo: APTN News)

Sgt. John O’Donovan, a homicide investigator with the Winnipeg Police Service said at the time, Fontaine had been exploited and taken advantage of.

She weighed a tiny 33 kilograms (72 pounds) when she was reported missing on August 9. Just one week later, her body was found.

A 15-year-old child who obviously didn’t put herself in the river.

(Tina Fontaine’s death shocked the country. She was from Sagkeeng First Nation north of Winnipeg, Man.)

Fontaine’s death was the impetus for finally addressing the tragedy of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls in Canada. A national inquiry was launched after much previous resistance.

(Hundreds of people gathered at the site where Tina Fontaine was found in 2014. Photo: APTN News)

Now, four years after her death, the sexual exploitation of Indigenous women and girls has only increased, according to police officials and advocates.

For After Tina Fontaine: Exploitation in a Prairie City, APTN Investigates and APTN News went on an exclusive ride-along with the Winnipeg Police Service’s Counter Exploitation and Missing Persons Unit to get a deeper understanding of exploitation in Winnipeg.

Hot Spots

It was a Friday afternoon in mid-June, with temperatures reaching as high as plus 30 degrees Celsius, as we jumped into an unmarked police car with our cameras, phones, and notepads.

The Red River Exhibition had just begun, a bustling fair held every year on the outskirts of the city. The “Ex” as it is locally known, is historically a busy time for the counter-exploitation unit.

(Winnipeg’s North End is just one place known for exploitation and missing youth. Photo: Martha Troian/APTN Investigates)

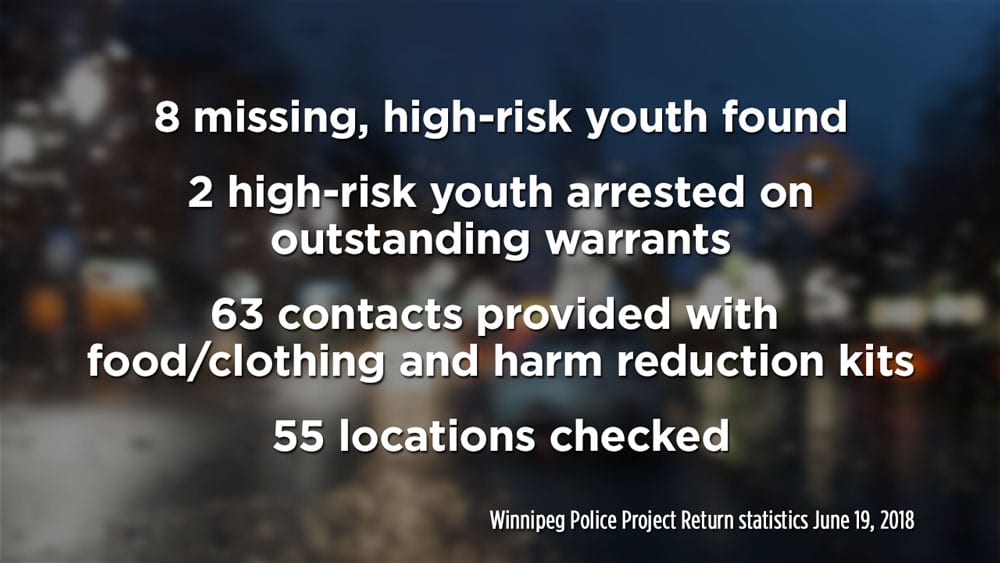

It is also the day that “Project Return” — a multi-prong unit made up of police detectives and agencies — are working together to protect exploited and missing children and youth. Since 2011, the joint task force has operated street sweeps at various times of the year.

Sergeant Rick McDougall, the unit’s leader, looks just like a suburban dad comfortably driving a car to a kid’s soccer game. But today he is driving APTN Investigates producer Holly Moore and myself around to showcase the grim realities of what exploitation can look like in this sometimes dangerous Prairie city.

(Sgt. McDougall with the WPS’ Counter Exploitation and Missing Persons Unit takes APTN Investigates for a ride-along on June 15, 2018. Photo: Martha Troian/APTN Investigates)

McDougall is part of a team of 12 detectives, three detective sergeants and four missing persons coordinators from the Winnipeg Police Service (WPS) that make up Project Return. Some of the detectives formerly worked for Project Devote; a joint task force between the WPS and RCMP that investigates unsolved homicides and disappearances of exploited people.

(Under a blue sky, Indigenous women and girls are seen hanging around near these tracks. Photo: Martha Troian/APTN Investigates)

As soon as we enter the car, we jump into a conversation and hit the streets. There is no time to waste. We first drive to the city’s North End, a known hot spot for exploitation and missing youth.

There we see several young Indigenous girls working the streets. We meet up with two detectives from McDougall’s unit who are doing wellness checks.

One young girl sits next to railway tracks alone, with several of her items scattered next to her.

(Some Indigenous women and girls are found high or coming down from drugs, making them more vulnerable. Photo: Martha Troian/APTN Investigates)

“She’s one of our high risk [and] she openly admits that its meth, [that is] her addiction,” said McDougall. “She’s selling herself to pay for it.”

Another young Indigenous girl is nearby. From a distance, we watch McDougall’s crew check in on her, offer her a cigarette and a conversation. They want to make sure no one is forcing her to be out there.

These visits are also intended as an opportunity to jot down her description, last known location and the time and date of the interaction, in case she goes missing.

(In between parking lots, homes and small buildings, young Indigenous women and girls are found standing around in the north end. Photo: Josh Grummett/APTN Investigates)

Shortly after, I make an attempt to talk with her. She looks familiar and I remember her face was previously plastered on a WPS’s missing persons report poster. Her brown eyes look bottomless and sad, an image I still can’t get out of my head. I can tell she’s seen a lot in her short life and I wish I could bring her home.

Next, we visit a ‘trap house.’

The Trap House

It is rush hour and the unit has been tipped off by someone from the Bear Clan Patrol; a grassroots patrol group, that a trap house is operating in the North End.

A trap house is usually a place where people go to do drugs. They attract users, buyers and sellers. But it can also be a place to pass out, too, explains McDougall. Most traps operate out of houses but some can be found in apartment buildings.

(James Favel, executive director of the Bear Clan Patrol Inc., said Tina Fontaine’s death was the last straw for him. He now dedicates his life to protecting the vulnerable. Photo: Martha Troian/APTN Investigates)

The Bear Clan Patrol is just one of the agencies working in partnership with Project Return. Other agencies include; StreetReach, Winnipeg Outreach Network, Resources Assistance for Youth — all known for working to protect exploited youth and vulnerable populations.

We meet up with two detectives in the North End dressed in full protective gear, driving in an unmarked car. They chatter about what they heard and strategize a plan of action.

“Even if we just wave the flag and let them know we’re just around,” said McDougall. “Sometimes you just bang on the door and somebody will walk right out.”

(McDougall shows us a ladder placed underneath the window of a trap house. Photo: Martha Troian/APTN Investigates)

The unit will visit a trap house because it’s a place where missing children and youth may go. Children as young as eight or nine years old have been seen in trap houses, usually because an older sibling is there.

“A lot of times we will get kids that will say, ‘Can I get a ride home?’” said McDougall.

He tells us trap houses are places where the grooming process for exploitation can begin. For instance, youth could be given drugs or alcohol inside and later told they have a debt to pay.

“We see that happen a lot, too,” the detective added.

Grooming can be done by anyone: a family member, a friend, a stranger, or even an intimate partner. It can happen through manipulation, buying clothes, gifts and drugs or alcohol.

“We get information about them, and then as soon as we find out about them another one will pop up somewhere else,” said McDougall, adding it is unknown how many trap houses are operating in the city.

This particular trap house is less than 200 meters away from an elementary school.

(McDougall said his unit does not visit a trap house to break up a party, it is only to recover any missing children and youth. Photo: Martha Troian/APTN Investigates)

Two detectives enter the house and minutes later a young male quickly comes out of the house. McDougall stops him to be questioned and then shortly joins the detectives inside the house.

(APTN Investigates Martha Troian visits a trap house in Winnipeg, Man. Photo: Holly Moore/APTN Investigates)

Once back outside, the detectives explain there were several young males and females either crashed out on couches or watching TV in the dark inside the house.

McDougall tells us that detectives are not there to arrest anyone on drugs, instead they just want to make sure everyone is there on their own free will and not reported missing.

No one inside was on a missing persons list. I can tell this disappoints McDougall.

What happens if a child or youth is missing under the age of 18?

“The Child and Family Services Act kicks in, we consider a child is in need of protection and we can apprehend them and bring them back to their guardian,” said McDougall.

The Exploited

We drive to the West End of the city and watch from the car as two women sit on a bus bench. They are being circled by cars, trucks in particular. There is definitely some action taking place here today.

My producer, Holly Moore and I approach them, offering cigarettes and water.

They seem reluctant to talk to us but eventually allow us to ask some questions.

(Like the North End, the West End of the city is also a known hot spot for exploitation and missing youth. Photo: Martha Troian/APTN Investigates)

One Indigenous woman who appears to be in her 40s is a mother to several children. She tells me she’s in the sex trade because she got high a few weeks ago and needs another hit. Her friend, who is in her early 20s, is Métis and has a long history of sexual abuse and is ostracised by her own family. She is also struggling with addictions. Both deny being forced onto the street by another person.

This seems to be a popular spot. A few weeks after, while on a separate trip with just an APTN News cameraman, I spoke to an Indigenous girl at the same corner. She had similar traits to Tina; she was young, pretty and vulnerable.

She giggled a lot when I asked her questions and denied being exploited or working the streets for anyone. However, I couldn’t help but notice her nervousness or the large black SUV that had sped up and idled next to us as I was talking with her. The driver was much older than her and well-dressed.

While it is not clear if these women were being exploited, Sgt. McDougall and his team are clear on the definition. Exploitation is compelling a person by force, intimidation or control to engage in sexual conduct in exchange for money, drugs and shelter. McDougall emphasizes that it’s all about the exchange.

(What may look like any other neighbourhood is actually home to Indigenous women and girls selling themselves, some of them possibly being exploited. Photo: Martha Troian/APTN Investigates)

He uses the term “high risk victim,” to describe a young person who has been identified at an elevated risk of exploitation and victimization. The average age for a female to be introduced to sexual exploitation is just 13-years-old in Canada.

Indigenous men and boys and two-spirited people can also be exploited.

Although there is a distinction between exploitation and sex trade work, the former sex trade workers, officials and advocates that I spoke to, say the two are interconnected.

Carrie and Brandi, two survivors of sexual exploitation shared their story with APTN Investigates and APTN News. They only want to be identified by their first names.

“I was exploited from seven years up by my mother and my aunties,” said Brandi.

“Making us crawl on floors to steal their [men’s] jeans so we can empty their pockets and put the jeans back in the room while they were doing those sexual favours.”

(An old makeup brush discarded on a strip where sex trade workers hang out. Photo: Martha Troian/APTN Investigates)

Growing up and seeing exploitation, Brandi said it became her lens and she learned from a young age that you can make money from your body.

(When she was just 14, Brandi first walked Winnipeg’s King Street. Photo: Josh Grummett/APTN Investigates)

Brandi said the first time she stood on a corner was on Winnipeg’s King Street at the age of 14.

“I did that a couple of times as a child… then I went into escorting.”

Even though Brandi made a lot of money from it, there was a price to pay.

(Among the debris found in the North End, was a discarded rubber band used for drug injection. Photo: Martha Troian/APTN Investigates)

“Along with the exploitation comes the severe drug addiction,” said Brandi. “The pimps would give us treats, being [the] good guys, not realizing that their intent was to get us hooked and give them all our money.”

Pimps, Johns, perpetrators or predators in After Tina Fontaine: Exploitation in a Prairie City are being used to describe people who exploit others or who pay for sex.

(When she was a child, Carrie said there was rarely a night when men wouldn’t come to her house from Main Street bars. Photo: Jared Delorme/APTN Investigates)

Carrie said she remembers her mother bringing men home from bars on Winnipeg’s notorious Main Street when she was just a young girl.

“I remember being violated as a really young child,” said Carrie, who said it happened when she was just six-years-old.

In her early teens, she started to hang out with girls who were already entrenched on the streets.

(After being exploited as a child, Carrie later hung around near the corner of King and Flora Streets in Winnipeg. Photo: Josh Grummett/APTN Investigates)

“My first time being exploited was on King and Flora, they use to call it the ‘kiddie track.’” She started at age 12.

Then the drugs came.

Carrie remembers using crack cocaine at age 14, and continued to stand on the corners for more drugs.

“I use to always say, the only talent I had was f*cking up or s*cking d*ck.”

(Discarded condom wrappers are found in an area known for the sex trade. Photo: Martha Troian/APTN Investigates)

Like McDougall, Carrie and Brandi said they can see exploitation is on the rise in the city. Today Carrie works with exploited youth.

Carrie believes many of the children and youth in care are vulnerable and at risk for exploitation. Given the high rate of Indigenous children and youth in the child welfare system, Carrie would like to see more supports for them.

Just 12 hours before Tina Fontaine was reported missing, she was in contact with police, security officers, child welfare officials and hospital staff.

Sgt. McDougall is aware of the high number of Indigenous children and youth in the child welfare system.

“One of the recurring themes that we get when we find them is they don’t like the placement that they’re in, it’s not home,” said McDougall.

The Perpetrators

Carrie and Brandi, two survivors of sexual exploitation said perpetrators know when it is an opportune time to prey on vulnerable Indigenous women and girls.

“They catch you at a time when you’re hurting, homeless and things like this so what’s a package of cigarettes for their entertainment?” said Carrie.

They said most of the perpetrators preying or picking up Indigenous women and girls are Caucasian men.

She said she could pick them out right away while she was working on the street.

“You know who they are right away and they’re driving around and around.”

(Several trucks and SUVs circled the women the day we went out for a ride-along with the WPS. Photo: Josh Grummett/APTN Investigates)

Carrie said her customers drove pick up trucks, rental cars and even work vehicles.

Many of the men were also well-established in their careers and included prominent citizens or married men, the pair said.

Brandi remembers going to a man’s home who worked in the medical profession when his wife was out of the house.

(Both Brandi and Carrie said most of their clients were Caucasian and married men. Photo: Josh Grummett/APTN Investigates)

Although no occupational analysis has been done before on Johns by the Winnipeg Police Service, Sgt. McDougall said the majority of men who buy sex in Winnipeg are between the ages of 40-60 years old.

And, they have money.

McDougall said in his experience, Johns are upfront with who they are, what they want and what they’re willing to give in exchange.

“Whether it’s money, drugs, alcohol [or] sometimes it’s a place to stay,” said McDougall.

Then there are the pedophiles, said Carrie and Brandi.

“I remember first going on ride-alongs,” said Carrie about joining experienced sex trade workers in a vehicle. “At that time the Johns would be asking ‘Can I touch you for extra money?’”

Carrie was 12-years-old at the time.

Brandi recalls a girlfriend who looked younger than she was while working in the sex trade.

(Brandi and Carrie said some men asked them to get girls as young as 12 years-old for sex. Photo: Jared Delorme/APTN Investigates)

“A lot of her clients would mention they had just came from watching children from the schoolyards.”

Both Brandi and Carrie said there were also times when they were asked to get a younger girl for men, and in return they would be paid ‘a finder’s fee’.

Trap houses, massage parlours, hotels, or a John’s home — are all places where these exchanges occur.

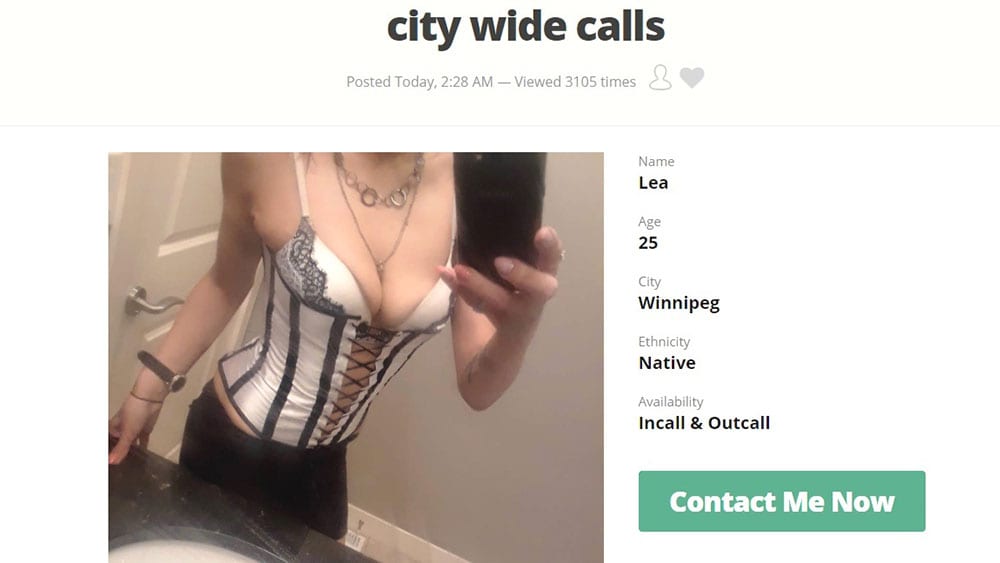

Sex for sale is also arranged online. Backpage – the once go-to website for exploitation and sexual services – was shut down in early April 2018 by U.S law enforcement agencies.

But hydra-like, another site just popped up in its place. Now, the demand for female escorts is satisfied by LeoList, a similar service and dozens of ads for female escorts including those who look quite young, can be found in its ‘Personals’ section.

(A site similar to Backpage, known for exploitation and sexual services before it was shut down. Photo: LeoList/online)

Family members have also been known to exploit their very own children, as in the case of Brandi.

Candace, an Inuk woman told APTN Investigates that she was exploited by her own mother from the time she was a toddler up to the age of 13-years-old. We are protecting her identity and we will bring you her story tomorrow.

Sgt. McDougall said that regardless of who is doing the pimping of a person under 18, harbouring charges and “material benefit” charges can be applied. They could also be subject to procurement charges. Identity document charges can be applied if a victim’s I.D. is being withheld or destroyed.

Project Return was a good night for the team — they found a number of missing youth and made contacts with those in the sex trade.

I can’t help but look at the city differently. I am left wondering who is being exploited and for whose gain.

I ask McDougall what keeps him up at night.

“The fear that one of our missing is going to wind up dead again,” he said stone-faced.

This is a reoccurring nightmare for him. But he doesn’t stop protecting exploited children and youth, nor his crew.

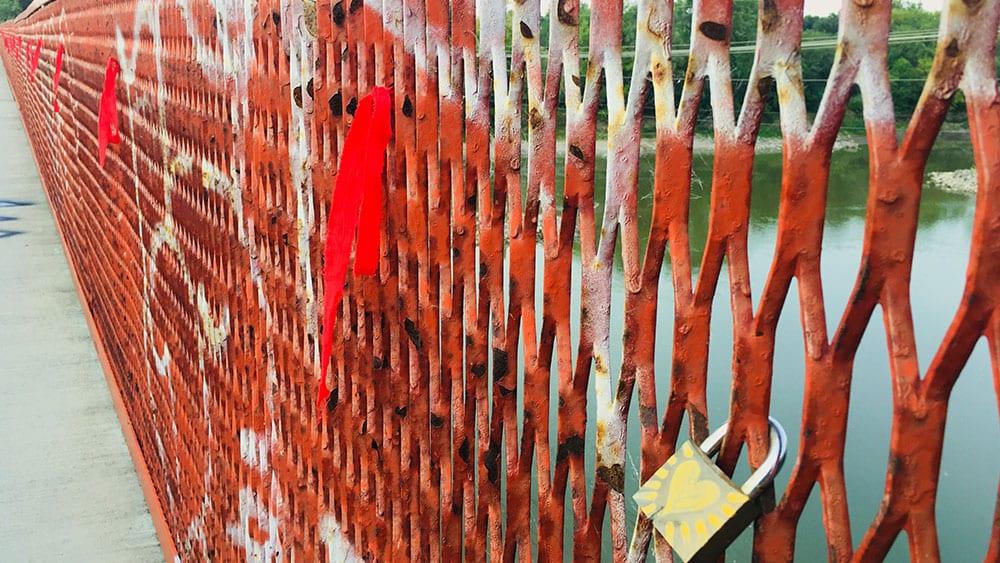

(Bridges in Winnipeg are embellished with red ribbons representing missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls. Photo: Martha Troian/APTN Investigates)

My cameraman, Jared Delorme and I drive to the Alexander Docks on the banks of Winnipeg’s Red River. It’s blocked off now but we come across a worn wreath, adorned with red flowers. We believe it was part of the many memorials to Tina Fontaine.

(This wreath sits at the Alexander Docks. Today, the country continues to heal from Tina Fontaine’s death. Photo: Martha Troian/APTN Investigates)

The sky is blue with cotton-like clouds, and there are overgrown weeds with bright pink creeping thistles and torn branches everywhere.

It makes me think of Indigenous women and girls; some are blossoming while others are not, and it’s not because they don’t want to.

They just need some help.

Thank you for the stories.keep searching.these youngsters need help.

I am a mother of 3 which one of my Daughters have struggled with depression and suicide .Her mother (my half sister) has grown up on the streets Addicted to solvents and other drugs. When ever I drive in the north end I always try and see if I would notice my half sister if I saw her .My daughter asks about her, my biggest fear as of many mothers of young women ,is I do not ever want this to happen to my child .I think that we as a community have a responsibility to all children whether they are your own or not .I thank the Bear Clan for doing such a great job working with the Wpg. police searching these homes and bringing family members together. lets not have another TIna Fontaine incident 🙁

Migweech

Mary

Thank you for the stories.keep searching.these youngsters need help.

I am a mother of 3 which one of my Daughters have struggled with depression and suicide .Her mother (my half sister) has grown up on the streets Addicted to solvents and other drugs. When ever I drive in the north end I always try and see if I would notice my half sister if I saw her .My daughter asks about her, my biggest fear as of many mothers of young women ,is I do not ever want this to happen to my child .I think that we as a community have a responsibility to all children whether they are your own or not .I thank the Bear Clan for doing such a great job working with the Wpg. police searching these homes and bringing family members together. lets not have another TIna Fontaine incident 🙁

Migweech

Mary