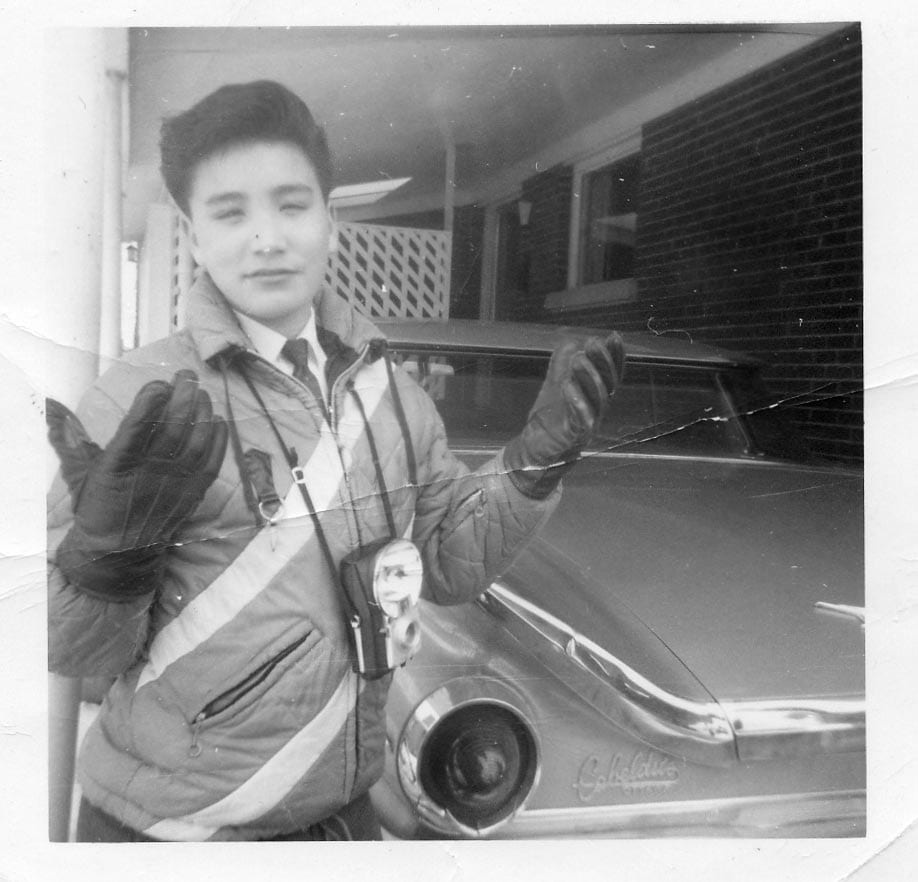

Zebedee Nungak was 12 years old in 1963 and doing well in school in his home community of Puvirnituq in Northern Quebec. When not studying, Nungak was out on the land with his friends, a .22 rifle in hand and dreams of being a great Inuit hunter.

But the federal government had a different plan for him.

They wanted to try an experiment.

By August of that year, Nungak would be on a plane bound for Ottawa.

“The government called it a social experiment or an experiment to see or determine if Inuit children could withstand being ‘educated’ in among white children in suburbia,” said Nungak.

In the early 1960s, three men were part of a program the Canadian government called the “Eskimo Experiment.” It was run by the department of Northern Affairs and National Resources (now Indigenous and Northern Affairs) to determine if Inuit children were smart enough to be educated in the south, and eventually become future leaders.

Peter Ittinuar from Chesterfield Inlet, Nunavut, Eric Tagoona from Baker Lake, Nunavut, (then Northwest Territories) and Nungak from Puvirnituq, on the eastern shores of Hudson Bay, were taken from their homes for more than six years – and had little or no contact with their friends and families in the North.

Now, nearly 60 years later, they want recognition and a negotiated settlement from Canada because they said the experiments forever changed their lives.

“The experiment was two-fold,” said Ittinuar, 67, who is a negotiator in the Negotiations and Reconciliation Division in the ministry of Relations and Reconciliation for the province of Ontario. “One was to see how well these kids do in the classroom and obtaining grade certification and all that, and secondly how well would they do socially and how well would they adapt culturally.

“And that experiment was to help them determine new policies up north, whether to bring kids down south and determine whether we were little savages or as good as well as white kids.”

To start the experiment, Ottawa needed to find test subjects – students who excelled in existing Arctic schools. The department sent a team across the North to administer Intelligence Quotient (IQ) tests to find the brightest Inuit students. And it seemed the department wasn’t concerned about what that would do to Inuit culture in the future.

“It can be argued that such a directed educational program will disrupt northern native family ties, and will rapidly destroy native culture,” said a departmental report. “We must follow through with the natural consequences of that program.”

Peter Ittinuar was a 12-year-old growing up as a typical ‘Eskimo child,’ learning to fish and hunt in his small community that sits on the northwestern shores of Hudson Bay.

“In 1960 there were still many, many people still living pretty nomadic lives and living out on the land at that time,” he said. “They were then starting to be herded into communities and you know small one room schools were being built. The question for the government was how are we going to educate all the Inuit up north en-masse? You know they’re isolated, they’re way up there do we bring them down south? Do we build schools up there?”

The program was administered by Gordon Devitt, the district superintendent of schools in the North.

Among their peers, Ittinuar and Tagoona stood out.

In late August 1962, the two 12-year-olds left from the airport in Rankin Inlet for their journey to join the Qallunaat (white people) in Ottawa.

“There was always a crowd at the airport when a DC-3 came in or the Northern Norseman single engine plane,” Ittinuar said. “I think my dad was actually working in the mine when I left, and I think it was my aunt took me to the airport … it was a day that changed my life.”

In Ottawa, the place of straight lines and paved roads, Tagoona and Ittinuar had access to everything.

They stayed with the same family and attended the J.H. Putman public school in the city’s west end. There, they excelled in their studies.

Their “Dick and Jane” English, as they described it, quickly improved and both immersed themselves in extra-curricular activities including judo, swimming, music and community sports including hockey and softball.

“In fact, one of the few things that encouraged me …,” remembered Nungak, 65 who is now a radio commentator and author. “Previous to this I thought the white people were some sort of superior race. That they never went hungry. All their women were beautiful and even their garbage was good. That was my stereotype impression of white people.

“But during one of my classes at Parkway public school in which I spent my first year in Grade 6, one of my fellow students, we were doing a reading exercise and he was struggling with a word, he was reading some text and he said ‘and he had to deter … he had to deter- mine’ and I was amazed. If he can, a Qallunaat boy can have trouble with words in his own language that I knew – he was trying to say determine … what am I doing feeling any sense of inferiority? And I never looked back.”

According to a letter penned in 1964 by R.L. Kennedy, the department’s superintendent of the Arctic, the boys were achieving “above class average,” and said, “they are capable of competing with children in southern Canada.”

“We recognized it started us on a road pretty much ahead of our peers towards an education that helped shape our lives,” said Ittinuar.

August 14, 1963 is when Zebedee Nungak set off on his own journey from northern Québec to Ottawa.

“I was a walk-in,” said Nungak. “I didn’t go through any IQ testing I just walked in. The late Ralph Ritcey who was one of the senior bureaucrats who was responsible for our care and supervision described it as such, as a “walk-in.”

Nungak said he remembered being excited the day he left Puvirnituq for Ottawa.

“I was a 12-year-old boy, very anxious to get on being in a strange environment among the Qallunaat,” he said. “I didn’t have any morbid fear of getting into this mysterious experience. And my parents were entirely supportive – they were not kicking and screaming.”

While Nungak’s parents were not “kicking and screaming” about their son’s departure, they didn’t know the government was conducting an experiment.

In fact, the government didn’t get the informed consent for any of the three boys to travel.

They just told them they were going.

Except for Peter Ittinuar’s parents.

“My mother was away at a (tuberculosis) sanatorium,” said Ittinuar. “My dad found out from a priest who had found out from a teacher who had found out from a government official and there were no consent forms signed … it was planned ahead but there was no consent. They did what they wanted to do.”

While Tagoona keeps in touch with both Nungak, and Ittinuar, he rarely has contact with the world outside Baker Lake, NU.

Both Nungak and Ittinuar agree there was a disconnect in the experience.

While they were receiving a good education, and living in a middle-class home, they had no one to turn to during hard times – but say they were not physically abused.

They received a far better education than that of their peers in the Arctic – and they would fulfill the government’s plan and become leaders of their people.

But as they grew older, the three recognized that this higher learning came at a cost.

They were not Inuit in the eyes of their family and friends in the North, and in the south, would never be accepted as Qallunaat.

“Whatever I gained from the experience chipped away at my core identity of being an Eskimo man,” said Nungak. “The one thing that I did learn was to speak and write and express myself in English well – well enough for natural English speakers to understand what I’m trying to get across.

“But that knowledge is absolutely useless when I’m at the floe edge hunting seals or walrus and I’ve caught one and now I have to butcher it – my knowledge of English is absolutely useless then – when I’m in my Eskimo element.”

“It was also an extreme struggle to regain our language and culture,” said Ittinuar. “And all the things that were truncated like hunting skills. Quite frankly there was also extreme reverse racism by our own people – and that one really, really, really hurt and I didn’t understand it for a long time.”

None of the three men learned of the government’s experiment until 1997.

That’s when a researcher from Trent University in Ontario discovered a series of papers on the “Eskimo Experiment” in the archives.

It changed how they felt about their experience – and now they want to be compensated.

“In essence, our clients were being treated like cattle,” said Steve Cooper, the lawyer retained by the three men. “They were used for government purposes. There was no proper consultation, there was no proper consultation of the families.”

In 2008, Cooper filed a statement of claim against the government for failing to live up to its fiduciary duty to protect the culture of the three men.

They’re seeking $350,000 each in damages.

“This is not a big dollar item. These are not huge claims,” said Cooper. “This is not a $50 million dollar claim that was used to resolve Labrador. It involves a very small group of people who were treated in a way that was contrary to the fiduciary duties of her Majesty at the time.”

The lawsuit has been on hold for years. That’s because, under prime minister Stephen Harper, government lawyers would often threaten to have the case dismissed on the technicality that it was past the statute of limitations.

Not entirely sure how the courts would rule the statute argument, Cooper and his Experimental Eskimos decided to lay low until there was a change of government, and possibly, a change of heart.

That happened in October 2015 when the Liberals formed the government and the message of a new “Nation to Nation relationship” was heard time and time again from Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.

“It has come alive again from its dormant state frankly because of the change of government and the consequent change of policy and particularly the statements in the TRC report,” said Cooper, who also represented residential school survivors in Newfoundland and Labrador – a case that went from battling in the courts under Harper, to a negotiated a $50 million settlement under the new Liberal regime.

Cooper said he recently sent a letter to the Department of Justice to find out if there was any interest in going to court and having a judge look at the merits of the case for the Experimental Eskimos – or whether Canada will continue to lean on the statute of limitations.

“We’re reminding them again about the Truth and Reconciliation commission (TRC) recommendations that the prime minister has pledged to follow in every instance, saying that litigation should be replaced by discussion,” said Cooper.

In 2016, Ittinuar sent an email to Jody Wilson Raybould, Canada’s attorney general, and a former regional chief for the Assembly of First Nation in British Columbia.

“This request is out of the blue but Zebedee Nungak and I thought there is no harm in asking for a brief meeting with you,” wrote Ittinuar in the email Sept. 30, 2016. “Many years ago both Zebedee and I worked alongside your father during the “constitutional wars” of the ‘80s.

“This request for a briefing meeting concerns three of us from the early to mid-1960s. A rather unusual and unique case officially called ‘The Eskimo Experiment’. We wondered if we might be able to meet with you sometime in the near future, at your convenience, for 15 to 30 minutes. We know your time is valuable, but we do want to apprise you of our case.”

Ittinuar never heard back.

“I don’t know if she even got it. I don’t know how things work at that level; whether an underling gets it and says look some crackpot,” said Ittinuar. “We’re hoping we can at least talk it out and see what we can do.”

Now the men have enlisted the help of NDP MP Romeo Saganash.

In 2015, the MP for Abitibi, Baie, James, Nunavik, Eeyou in northern Québec, and Nungak’s representative in Ottawa, rose in the House of Commons and read a statement.

“As with the residential school system, the impacts and consequences the policy would have on the children were never considered. This past week, the parties involved in the class-action suit for residential schools in Newfoundland and Labrador have finally reached an agreement and settlement, which, as a survivor myself, I applaud,” said Saganash.

“It is in the same spirit of reconciliation that the Government of Canada needs to do the same in favour of the Experimental Eskimos. The survivors of this other dark chapter of our history are calling on us to help them, so they too can turn a page on injustice, with dignity and honour.”

Saganash said he’s been working the file since 2011.

He applauded the signing of the Inuit Nunangat Declaration between Canada and the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK) in February. The document is supposed to guide Canada towards reconciliation with Inuit around relocation programs of the 1950s, and treatment during the tuberculosis epidemic.

He said it’s time Canada came through for Ittinuar, Nungak and Tagoona.

“I’m hoping the feds are honest with this process that they’ve established. That it’s not going to be all talk and no action,” said Saganash. “This is one beautiful example where they can show leadership and action.”

According to Ittinuar, ITK President Natan Obed mentioned their case to Trudeau during their Iqaluit meeting.

APTN asked the ITK what was said, but Obed did not make himself available for an interview. But a spokesperson for the organization said, “we support them.”

Trudeau has promised to implement all 94 calls to action listed in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s 2014 report.

The one of particular interest to Ittinuar, Nungak, and Tagoona is Number 26.

“We call upon the federal, provincial and territorial government to review and amend their respective statue of limitations to ensure that they conform to the principle that government and other entities cannot rely on limitation defences to defend legal actions of historical abuse brought by Aboriginal people.”

The government is leaning on the statute of limitations because it took Ittinar, Nungak and Tagoona 11 years to file their lawsuit after they learned of the experiment.

Nungak said they were all cautious.

“I said, ‘Peter, I suppose now, in pursuit of compensation, we’ll have to expose the unsavoury dysfunctions we have all experienced post-experiment. Broken family ties, inability to maintain healthy relationships, and, in my case, struggles with severe alcoholism,’” said Nungak.

“It took us years to sort of self-assess – what has it cost me? What has this cost me in my own individual personal life? I have never been close to my family ever again – although I have four brothers and two sisters, all still living.”

Both have talked publicly about their past personal issues now.

They said that is behind them.

The government did get what the experiment sought out to do – all three men became leaders, and instrumental in the development of Nunavut and Nunavik for the Inuit.

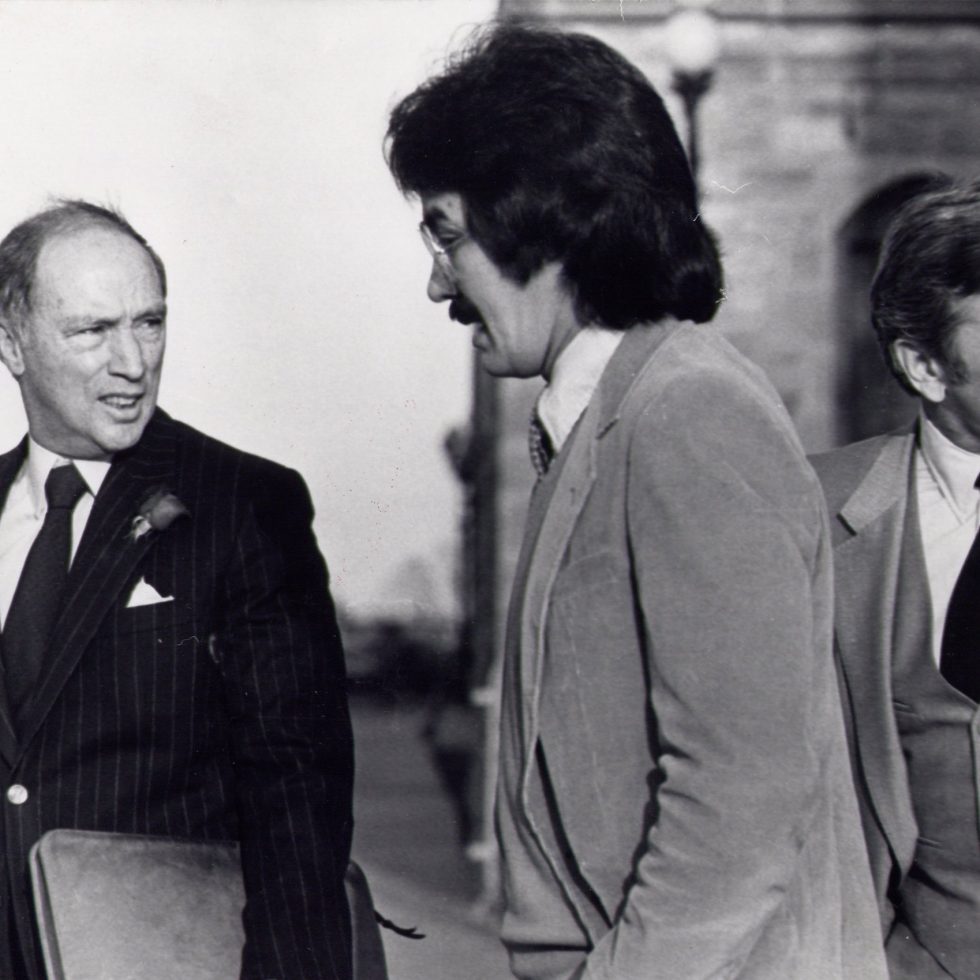

In the early 1970s, Nungak helped negotiate the James Bay Agreement that would create Inuit rights for the first time in Québec. Those negotiations also created the Makovik Corporation that represents the 15 communities of Nunavik, politically.

Ittinuar and Tagoona worked on the political front with the Inuit Tapirisat of Canada, later the ITK.

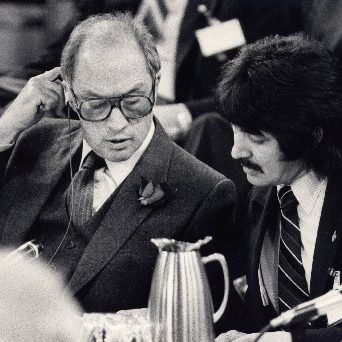

In 1979, Ittinuar became the first Inuk Member of Parliament representing Nunatsiaq, later Nunavut for the NDP. Later he would cross the floor to join Pierre Trudeau’s Liberals.

In the 1980s, all three were deeply involved with constitutional talks with the Canadian government including language used in the repatriation of the Constitution.

Nungak currently lives in Kangirsuk, Nunavik.

Ittinuar lives in Brantford, Ont.

Tagoona lives in Baker Lake, NU.

This lawsuit is only part of “Experimental Eskimo” project.

Later, four more children would be plucked from their homes in Nunavut and sent south to sink or swim.

Sarah Silou from Baker Lake, NU was sent to Edmonton, Alta.

Leesee Komoartok, Roasie Joamie and Jeanne Mike from Pangnirtung, NU were sent to Petite Riviere, Nova Scotiia.

Their claim is almost identical to the one Ittinuar, Nungak and Tagoona filed. Now everyone is waiting.

“I try not to be angry, and bitter and whining and complaining and just being a miserable fellow for having gone through all this,” said Nungak. “My only complaint now is that the government should recognize that they ran an experiment – they ran a human experiment without informed consent of our parents and they owe us for work we did in that experiment. But I try not to express it in terms of bitterness and hatred.

“All we want is let’s get paid for what we did and we’ll sign a release and we’ll call it a day,” said Ittinuar. “We’ll go away, you can go away and that will be the end of that – we don’t want an apology.

Justice must be served.