Karli and Tanner Armstrong once believed the case was shut for good, the two women convicted of killing their father, Casey Armstrong, faced life in prison, the crime punished, but now they face a reality where they may never see anyone brought to justice for the murder.

Over the past six years the siblings endured their father’s murder and then the total unravelling of the case against the two women—Connie Oakes and Wendy Scott—who police and the local prosecutor said drove to their father’s Medicine Hat, Alta., trailer in a red car, walked in through the unlocked door and killed him in cold blood over the Victoria Day long weekend in 2011.

They are now no closer to finding justice for Casey Armstrong’s murder than they were on that distant Sunday when the sudden news of their father’s death shattered their lives.

“It sucks. It’s been six years and now we are back to square one, nothing. There is nobody in jail, maybe nobody will ever get charged, and it’s hard to go on with your life,” said Karli Armstrong. “And you get calls, oh we got to go back to court, we have to do this. One time it was on Tanner’s birthday, once it was on my birthday or right before Christmas and then it starts to get you down, going through it all again.”

When they received the call this past January from the Crown’s office to set up another meeting, Karli and Tanner Armstrong had a sense of what was coming.

Wendy Scott, the woman who tearfully apologized to them in court for her role in the murder, the woman with a severe intellectual disability on whose testimony the Medicine Hat police and the local Crown prosecutor built their entire murder case on, was scheduled to begin her trial in February.

A preliminary hearing was scheduled for the end of January. The Alberta Court of Appeal ordered the new trial in October 2015 after striking Scott’s earlier guilty plea for murder and overturning the conviction following an admission from the Crown’s office that there was a serious error in her case—the facts did not support the guilty plea.

For the Armstrong siblings, the scenario felt like a replay of what happened months earlier when they were told the Crown prosecutor would be seeking a stay of the second-degree murder charge against Scott’s co-accused Connie Oakes, the Cree woman initially convicted of putting a knife through their father’s throat in the bathroom of his trailer.

Citing “frailties” in the evidence against Oakes, the Alberta Court of Appeal in April 2016 overturned her murder conviction and ordered a new trial that never materialized as a result of the stay.

“So the night before, I was thinking, the last time we had a meeting like this they let Connie out, so I’m like, oh my God, what if they are doing that tomorrow? What if they let Wendy out and we have nothing,” said Karli Armstrong. “I said, ‘I’m going to lose it if they do.’”

When the moment came and they were told the Crown prosecutor handling the case would be seeking a stay of the second degree murder and conspiracy charges against Scott, the anger didn’t materialize.

“I just sat there. I was just like, ‘What?’” said Armstrong. “I had no idea what to say.”

One of the prosecutors, who Armstrong believed was from Calgary, told them the justice system may have reached the limit of its ability to hold anyone to account for the murder.

“They just said, it’s likely that somebody might not ever be found guilty for it,” she said. “Just lack of evidence, I think.”

For a while, it seemed so clear. Scott admitted her involvement in the killing of Casey Armstrong, pleaded guilty, received a life sentence with no chance of parole for 10 years and became the star witness in the trial against her co-accused, Connie Oakes.

Oakes, on the advice of her lawyer, did not testify during her trial. Despite the lack of DNA, fingerprint or murder weapon evidence along with numerous inconsistencies and contradictions in Scott’s testimony, a Medicine Hat jury found Oakes guilty of Casey Armstrong’s murder. She received a life sentence with no chance of parole for 14 years.

Then, from prison, Scott began to say Connie Oakes wasn’t at the trailer the night of the murder. She also accused the Medicine Hat police of coercing her, of manipulating her intellectual disability—she has an IQ of 50—to produce the answers they needed to construct the case against Oakes and secure a conviction.

Without Scott, there was no case against Oakes.

Medicine Hat police investigators failed to nail down the most basic elements from the crime scene. Police never found the source of a bloody boot print left on the bathroom floor or identified the owner of a magnetic beaded necklace found atop the washing machine in a large pool of blood.

During Oakes’ trial, the Crown also never submitted evidence on the red car, which police believe, was used in the murder. Details around the ownership of the red car led to a woman with red hair who went by the nickname “Ginger.”

An eye witness, the manager at Peanut’s pub, a bar situated across the street from Casey Armstrong’s trailer, testified she saw two women, including one with red hair wearing a ball cap, putting a bag into the trunk of a red car parked outside the trailer on the Saturday morning of that fatal Victoria Day long weekend in 2011.

“I feel that Connie and Wendy did it, I’m pretty sure, for one reason: Connie and my dad were supposed to be friends back in the day and in the whole court case she couldn’t look at us, you know. You would think she had some sympathy, our dad just died, all of our dad’s friends went up to us. Wendy wanted to apologize,” said Tanner Armstrong.

Before her sentencing hearing, Oakes wrote a message she wanted to tell the siblings, expressing sorrow for their father’s death, but also maintaining her innocence. Her Edmonton lawyer Daryl Royer advised against it. Oakes met Casey Armstrong through her ex-husband and he once babysat one of her sons.

It was Scott’s courtroom apology at the time that really convinced the siblings the right women were heading to prison for the murder.

“She cried to us, ‘I am sorry we did it.’ It was the most sincere apology. Like, if she didn’t do it, she couldn’t make that up,” said Karli Armstrong.

Doubts now spread roots deep into their once held certainty.

“But then, I don’t know, I think, holy fuck, I don’t even know. This investigation is so crazy. They got nothing besides Wendy and who fucking knows what she even means because she lies so much,” said Armstrong.

The day Karli Armstrong found out her father died began with a walk with her mother in a pasture to name the year’s first calf. She remembers the silver Pontiac Sunfire driven by her boyfriend Chad Tokamp who was gunning it across the pasture towards her. She remembers her mother’s alarm at the speed of the approach.

Moments earlier, at the farm house a couple of kilometres away, Tokamp received a call on his cell phone from his mother. The local television station was reporting yellow tape around Armstrong’s father’s trailer in Medicine Hat, Alta. Tokamp then turned to Karli Armstrong’s brother Tanner Armstrong.

“I was standing right by him,” said Tanner Armstrong, remembering. “I asked, ‘What was that all about? And he said, ‘Dude, it sounds like something’s going on at your dad’s house, and it doesn’t sound good.”

Tomkins ran outside the house and grabbed the wheel of the Sunfire, which belonged to Karli and Tanner Armstrong’s mother Debbie Kendall. Tanner Armstrong, still in shock, slid into the passenger’s seat as the wheels spit and spun down a gravel road to the barbed wire gate and through to the pasture. They sped past cows grazing.

Karli Armstrong saw the Sunfire “ramping” across the pasture.

“Chad came running out and opened the door, ‘We gotta go, we gotta go, your dad is dead,’” said Karli Armstrong. “And I was like, ‘What? Shut the fuck up!’

As they sped back to the house Tomkins told his girlfriend he heard Curtis Harvey, one of Casey Armstrong’s closest friends, found the body.

“So I called Curt and I said: ‘Is he okay, where is he?’

“He said: ‘No, he’s gone.’

“And my mom started calling family,” said Karli Armstrong.

Armstrong wept most of the three and a-half hour drive from her mother’s farm, which sits east of Swift Current, Sask., to Medicine Hat. The police told them to go straight to the station once they got into town, but Armstrong needed to go home first.

She vomited in bathroom. Tanner Armstrong vomited off the deck.

“Then we went to the police station,” said Karli Armstrong.

“I honestly can’t remember anything after that, the whole day after we found out,” said Tanner Armstrong, who was living with his father at the time of the murder. “I really didn’t care about who did it or what happened. My dad is gone. I didn’t know anything…I was just really sad, the whole time I was just in shock, the whole drive back to Medicine Hat.”

Casey Armstrong was a pool shark and, when not too deep into the brew, could clear the table on anyone in and around Eastend, Sask. He honed his game at the bar in the Dollard Hotel in the Saskatchewan farming town by the same name. His good friend Greg Tysseland would skip high school classes sometimes to hang out with Armstrong, who was a couple of years older, drink Labatt’s Club and cross cues.

“Casey was a deadly pool player, we used to play a lot of pool and went to a lot of pool tournaments together,” said Tysseland, who met Casey after moving to Eastend in 1977. “We did not do too bad at times. Sometimes Casey would end up drinking too much by the end of the night, but I wasn’t near the pool player he was.”

Armstrong was born in Eastend, a small Saskatchewan farming town about 220 km east of Medicine Hat which had a population of 723 people in 1981, according to provincial statistics. He was the youngest of six children in a ranching family—he had four brothers and one sister.

“The Armstrongs are a big family and an old family in the community…They all had their roots there forever,” said Tysseland.

Casey’s father Buster Armstrong was a rancher, bred racehorses and ran an off-the-books veterinarian practice, according to Tysseland.

“I don’t know how well he and his father got along,” said Tysseland. “I know he was extremely close to his mom Myrtle.”

Casey Armstrong did not get into ranching, but made his money working for ranchers and doing odd jobs here and there. He also helped build the town’s ice rink. When Tysseland met him, Armstrong was renting a house that was kept immaculately clean.

“His house looked like a woman’s, it was crazy clean,” said Tysseland. “I think his mom made him that way. Her house was always spotless, everyone kind of gave him a hard time about being such a woman.”

Tysseland remembers those days in Eastend with a slight smile, when their world was demarcated by drives down country roads with the radio on, a card game later, a night of beer drinking ahead, no thoughts beyond.

There was that time, high on magic mushrooms, when they sprung a raccoon from a box down in the old farmer’s basement. Or that day in the Grand Marquis with no plates doing 120 km/h down a road with hills made perfect for ramping and then they hit that last one.

“You know when everything goes still? The car just took off and when it came down, it came down on its nose, bent the car in half,” said Tysseland. “I remember Casey saying, ‘hang on boys, this is going to hurt.’”

Armstrong walked away with a slight trickle of blood running down his nose, said Tysseland. They packed up their booze, walked across a muddy field to a neighbour’s house, called another friend to pick them up and they were off again.

“There were some crazy times, things were pretty open back then,” he said. “It was quite the days when we were young.”

There was also the time when Armstrong became the trainer for the local senior hockey team, the Eastend Jets.

“He was in his glory,” said Tysseland. “Senior hockey was taken fairly seriously back in those days and he was part of it. He could have been the captain of the team in his mind. For all of us too, it was good to have a guy there in that depth in that part of the organization…. Back in those days, after the senior game, it was always full of people, there was always a party.”

Tysseland said everyone knew Casey Armstrong in town. He was the life of any party he rolled into.

“Casey was as well-known as anybody ever was in that town,” he said.

Armstrong met Debbie Kendall and they lived in Ravenscrag, Sask., before moving to Medicine Hat. They had two children, Karli and Tanner Armstrong. The marriage, eventually, fell apart.

“It was a definitely a blow, I could see it hurt. He loved her, right. Some things are supposed to last forever and we all know that they don’t,” said Tysseland.

Armstrong also suffered from genetically bad knees made worse after a serious accident on a construction project expanding Medicine Hat’s wastewater treatment plant.

“Even Casey made the comment about the pills and things, ‘The goddam system made me a junky,’” said Tysseland. “I looked at his knees and it looked like a roadmap of scars, I don’t know how many countless knee operations he had. It’s a bad deal, but that’s what they give you.”

Life wasn’t easy for Armstrong. After the split, he fell into periods of darkness and some of those closest to him turned their backs, said Tysseland. Armstrong pulled through. He managed to stay employed for a while, out on the pipelines. He never cried the blues.

“He was the one who would listen to my problems. He’d take a stand and try to comfort a guy through it, whereas maybe he’d be suffering in his own deal,” said Tysseland. “He looked out for other people more than himself. He made the best of what it was, whether he had a mask on or not. That was the one side of Casey. He was a tough nut to crack.”

Near the end, money problems were weighing Armstrong down. He needed to pay rent, but the work wasn’t there anymore.

“Towards the end there was a lot of that stress,” said Tysseland. “I’d come up and take him over to Peanut’s pub and say, ‘Let’s have a steak sandwich.’ And he’d say, ‘No, buy me a beer.’ And I’d say, ‘No, you are going to have a steak sandwich along with your beer because I know you are not going to have any food.”

Tysseland’s last conversation with Armstrong was a short, catching-up type of phone call. Four days later, while he was in the basement of his Eastend home with a friend who was helping him move weights received a phone call that Armstrong was dead, murdered.

“It went in one ear and out there other. It took a couple of minutes and it kicked in,” he said. “I had to leave and go to a room by myself, basically. I couldn’t deal with it with everybody else at that point.”

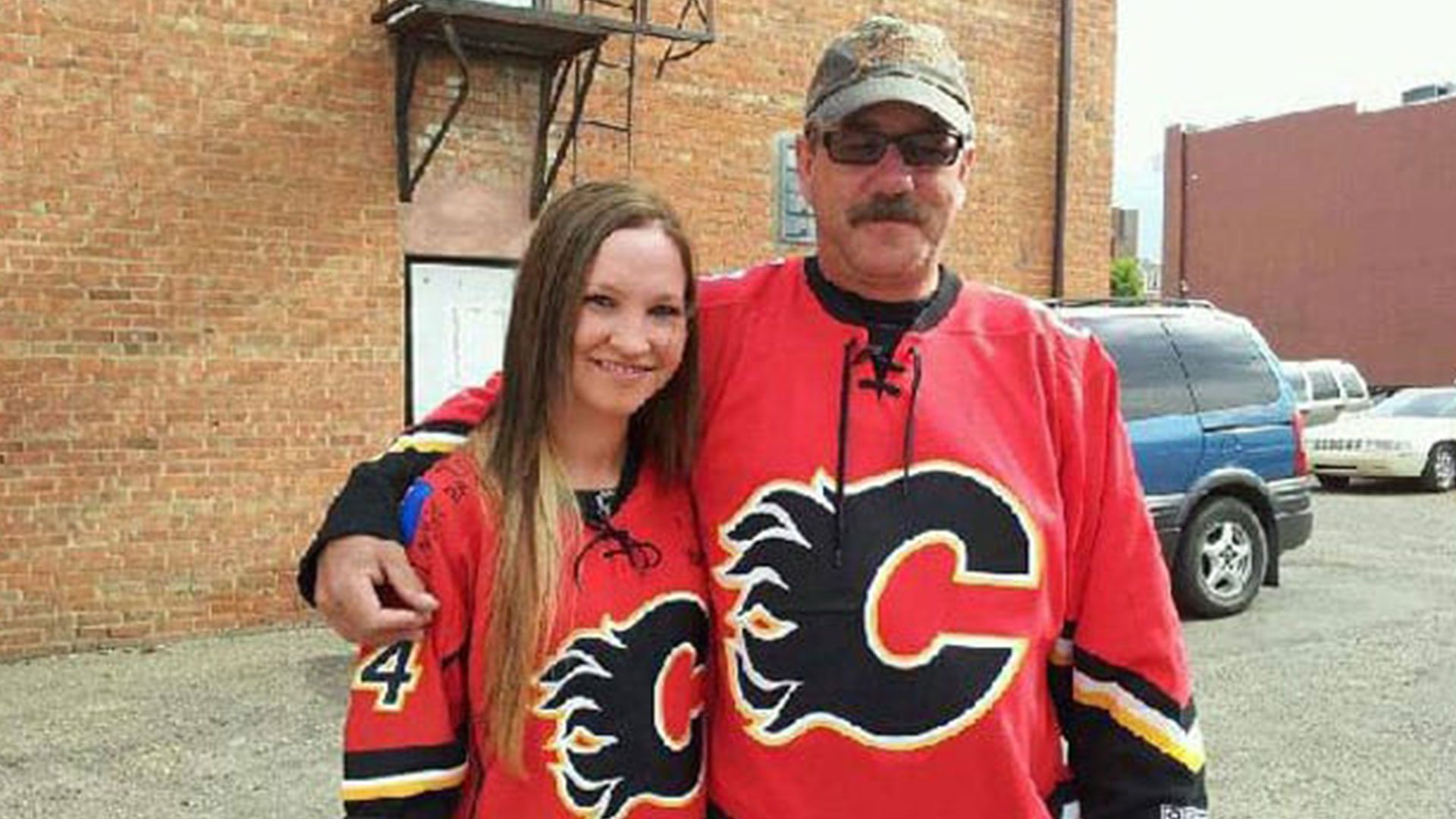

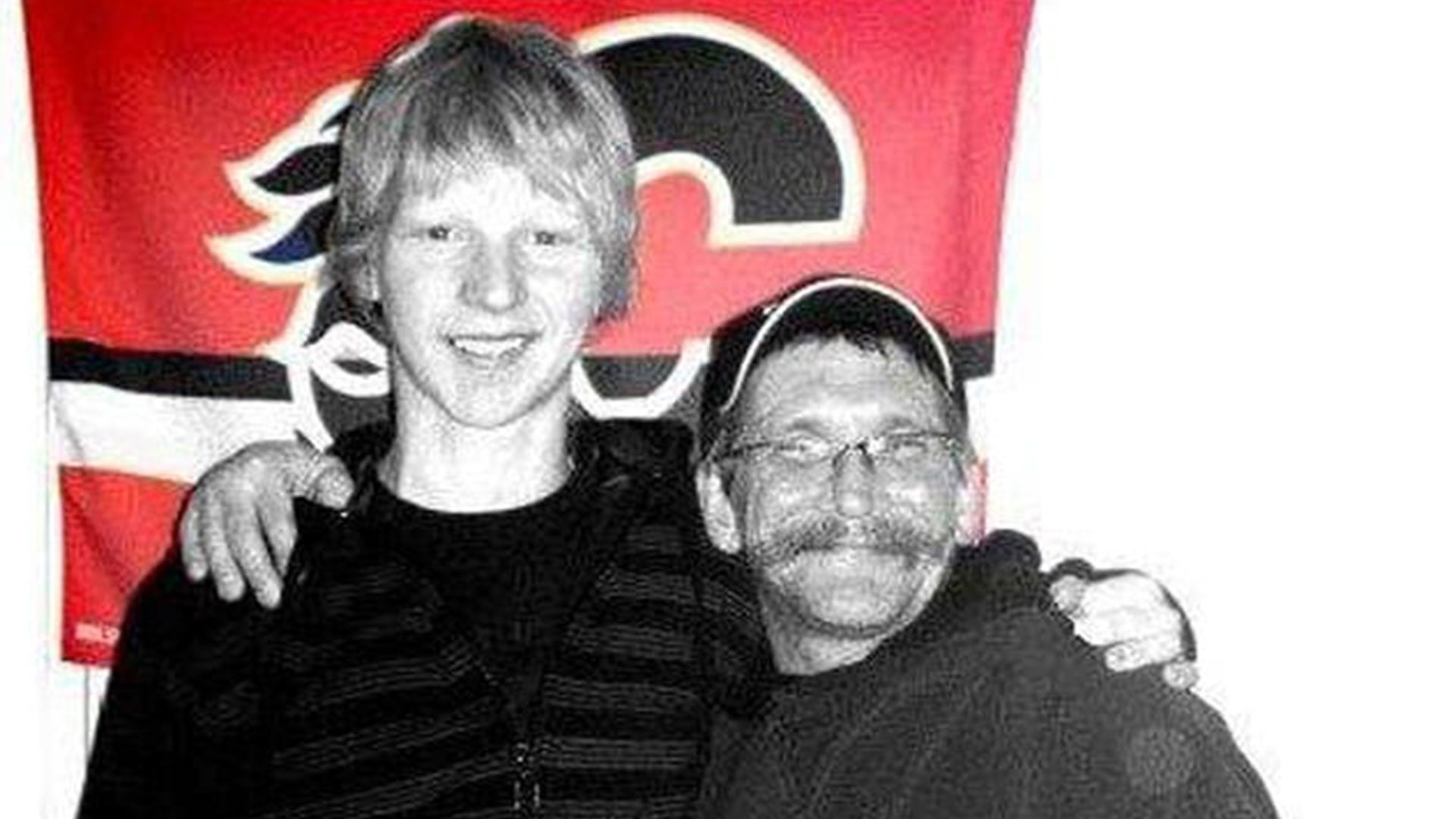

There are things that were easy to know about Casey. He loved the Calgary Flames, loved them since before the red-mustachioed glory days of Lanny McDonald. When it came time to watch the game, Casey would require silence and full attention on the struggle about to unfold across the blue lines.

He loved his beer and the music of Merle Haggard, Jonny Lang and the Tragically Hip and played air guitar in the kitchen while stomping his foot.

There was also more, beneath the surface.

“He just had a heart of gold, he did,” said Tysseland. “He was one of them guys, hard to beat. After getting as many Phd’s in life that I got, you couldn’t get a better guy. He was just a friend through and through. Our friendship continued, I made sure it did.”

Casey Armstrong won $250 playing the video slot machine at Peanut’s pub on his last night on earth. Casey bought the bar patrons a round of drinks and, after playing a little pool, shuffled out through the doors and across the street to his trailer to watch the hockey game.

He was wearing his Calgary Flames slippers mended with duct tape. The Vancouver Canucks were playing the San Jose Sharks that Friday night, May 20, 2011, in Game 3 of the Western Conference final. He settled in to watch the game with a Rainier beer and a Percocet pill. He was wearing a black, magnetized beaded necklace.

Armstrong bought the Percocet earlier in the day with a prescription for his chronically bad knees. Armstrong didn’t have a driver’s license as a result of an incident during his Eastend days involving a crash between his blue Ford truck, which was fraudulently plated with farmer’s plates, and a rich farmer driving an Oldsmobile.

He relied on friends to drive him around. That Friday morning Curtis Harvey, a long-time friend and school bus driver, dropped in to play a few games of crib with Armstrong. He then drove Casey to the pharmacy to pick up the prescription.

Somewhere along the way, Armstrong withdrew all his money, to the last cent, from his bank account. They spent some time at the Royal Hotel, Casey’s favorite bar with the mural on the outside wall of Jimmy Hendrix, a Harley Davidson and a poker hand with the ace of spades. Harvey dropped Armstrong off back at the trailer sometime after 6 p.m.

On Sunday morning, May 22, Armstrong wasn’t picking up his landline phone or his cell. Harvey kept trying and trying. Finally, Harvey put six beers into a cooler and drove to Armstrong’s trailer. It was about 10 a.m. and the door was locked.

Armstrong sometimes locked his door while home and Harvey knew there was a key underneath a pillow on the porch. When Harvey opened the door he saw shoes scattered at the entrance which was an aberration for someone who kept his home immaculately clean. The television was on.

Harvey walked deeper into the trailer and found Casey dead in the bathtub wearing a white Calgary Flames T-shirt and dark Calgary Flames sweat pants—blood everywhere.

The moment broke Harvey.

“I had some problems afterwards. I went to see a counsellor a couple of times. She helped me out quite a bit,” said Harvey. “When I went to see that counsellor, I was having a rough time. She told me that’s understandable, but when it starts to happen, just try to think of any of the really good times you have and there were thousands of good times we had together.”

Medicine Hat police investigators were never able to identify the source of a bloody boot print found on the bathroom floor. They went down to the local Wal-Mart and checked every boot. They took Tanner Armstrong’s shoes. They sent the tread marks to the RCMP. They still came up empty.

There was another item in the bathroom investigators failed to identify: the owner of a magnetic beaded necklace found on top of the washing machine in a pool of blood.

The pool of blood was described by Const. Kyle Bastel during trial testimony as being about a foot wide. In a photograph submitted as evidence, it appears as if the blood is pooled on an indentation atop the washing machine. During the preliminary hearing, Const. Carrie Bohnet said the magnetic necklace was stuck to the top of the washing machine.

Sgt. Ernst Johannes Fischhofer, with the forensics unit, testified he did not know where the necklace came from.

Casey wore a magnetic beaded necklace that matched the one found in the pool of blood atop the washing machine.

How the magnetic necklace ended up stuck to the washing machine in a pool of blood was a question the police never answered. It’s unclear if it was ever really asked. The version of the killing provided to investigators by Wendy Scott did not provide room for the answer. In her story, Casey fell on the floor after he was supposedly stabbed by Connie in the neck.

Harvey doesn’t believe Medicine Hat police will ever admit their mistakes in the case.

“They are a bunch of Keystone idiots when it comes to do with this entire thing and they proved it, not only in this case, but several other cases that there has been in Medicine Hat. I don’t think all cops are bad, by any means, I think there are far more crooked cops that look after their own selves before they worry about the public. There is a blue line and they will protect their friends on the force, whether illegally or not,” said Harvey.

“Right now, I don’t think they have the slightest clue who did it and they spent so much time focusing on Connie. If it wasn’t her, whoever it was is in the wind now and they will never find out. They probably think that. I think they’ll keep claiming they had the right person, whether they did it or not.”

Harvey said he was convinced of Connie Oakes and Wendy Scott’s guilt after the trials. Now, he just feels doubt.

“I can’t say I am certain, or as certain as I was,” he said.

Casey Armstrong said he hated dogs. He hated them until he met Shaggy, the Pekingese. The dog was found wandering alone by Karli Armstrong’s mother and a friend while rollerblading.

Karli Armstrong kept the dog for about a week and put a notice in the local newspaper hoping to find the owner. A woman finally called and said it was her dog, but her husband was allergic and she wondered if they could keep it. Casey Armstrong agreed.

“The dog wouldn’t leave him alone. We would try to cuddle with him, but he would always hop up with my dad,” said Karli Armstrong.

When Shaggy died, Casey Armstrong was “devastated,” said Karli Armstrong. They built Shaggy a coffin. There was a ceremony in the backyard of the trailer. They lowered the casket into a freshly dug grave with string.

“Someone let the string out too fast and one side fell and my dad was just bawling,” she said.

Karli and Tanner Armstrong, along with Greg Tysseland all have a tattoo with the letters KC on their hand by a knuckle. Karli Armstrong tattooed her father’s name in her father’s script on the inside of her left arm. She named her first daughter Kaci.

One summer night, after a friend’s engagement party, shortly after the death, she found herself on her father’s trailer steps weeping.

It rained the Sunday of that Victoria Day long weekend when Casey Armstrong was found.

“The rain always makes me think about him,” said Karli Armstrong. “And those rainy days, it was like his couch days and he wasn’t doing nothing but laying on the couch. The rain always makes me think about him.”

Karli and Tanner Armstrong still remember that Friday, May 21, 2011, the last day they saw their father alive. As they pulled away from the trailer headed for their mother’s farm east of Swift Current, as was their tradition, they gave the horn a quick double tap.

Casey Armstrong was on his trailer’s porch and gave them the peace sign, high in the air.

“It was his favorite weekend. He loved the May long weekend,” said Karli Armstrong.