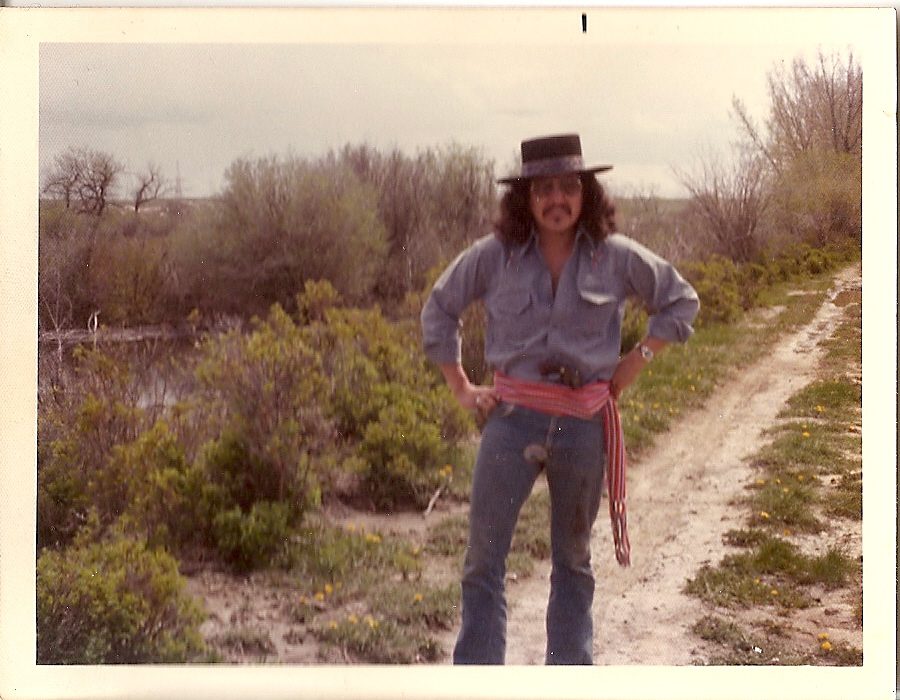

(Gabriel Daniels, right, with his late father Harry Daniels.)

Kenneth Jackson

APTN National News

OTTAWA – As Gabriel Daniels walked up the stairs of the Supreme Court of Canada Thursday people were rushing down, hugging him and saying, “We won!”

Daniels was arriving a little late to hear that the country’s highest court had just declared Metis and non-status Indians “Indians” under the Constitution Act of 1867.

“They were cheering and saying, ‘We won,’ but what did we win? Did we win everything?” he recalled afterwards.

They basically did – read the full story on decision here.

Daniels was briefed by lawyers on exactly what they won – potentially the same rights as status Indians, a fight his late father Harry Daniels started in 1999 with Dwight Dorey when the pair first took the government to court for the rights of the Metis and non-status Indians.

After Harry Daniels died in 2004, his son picked up where he left off and “immediately” added his name to the court action.

The carpenter and part-time actor was no politician, but knew what the fight meant.

“I knew what the case meant to (my dad) and, not only that, I knew what it meant to all us,” he said.

After lawyers briefed him, Daniels came down to the main foyer of the Supreme Court where representatives of groups of various Metis and non-status organizations were giving media interviews.

The politician’s son quickly found himself being pulled into the circus.

When one interview would wrap up, another reporter was pulling at his jacket collar – television, radio, print, online – even people asking him to sign the court’s decision.

“It happened pretty fast. I was overwhelmed,” said Daniels, a father of two girls who flew in from Winnipeg. “I haven’t had a chance to sort of breathe and let it sink in.”

The Supreme Court ruling provides a starting point for Metis and non-status who now have to take their case to the federal government, which could take years.

The court was asked to rule on three points – that Metis and non-status were “Indians” under section 91(24) of the Constitution Act of 1867, that the federal government had a fiduciary duty and an obligation to negotiate and consult on their rights.

The court granted the first point and found existing laws already obligated the federal government of fiduciary duty and negotiate or consult on their rights.

But how those existing laws can be used by the 600,000 Metis and non-status Indians remains to be seen.

“They are all ‘Indians’ under s.91(24) by virtue of the fact they are all Aboriginal peoples,” wrote Justice Rosalie Abella, on behalf of the court’s unanimous, 9-0, decision.

The court also determined there doesn’t need to be a “consensus” on who is considered Metis.

“’Metis’ can refer to the historic Metis community in Manitoba’s Red River Settlements or it can be used as a general term for anyone with mixed European and Aboriginal heritage,” Abella wrote. “There is no consensus on who is considered Metis or a non-status Indian, nor need there be. Culture and ethnic labels do not lend themselves to neat boundaries.”

Metis and non-status Indians have consistently found themselves in a jurisdictional “wasteland” when it came to securing rights. The federal government has argued s. 91 (24) precluded the Crown from assuming legislative authority over them.

When they turned to provincial governments they were often refused on the basis the issue was a federal one.

“It is true that finding Metis and non-status Indians to be ‘Indians’ … does not create a duty to legislate, but it has the undeniably salutary benefit of ending a jurisdictional tug-of-war in which these groups were left wondering about where to turn for policy redress,” said Abella.

The Supreme Court didn’t fully explore whether non-status Indians are “Indians” as Ottawa conceded that they are at trial.

Determining who is Metis and non-status Indians will be decided by a “case-by-case” basis going forward, the court ruled.

The ruling cements the legacy of Harry Daniels, who is best known for getting Metis in the Constitution, 1982, said his son.

But it also the legacy of Dwight Dorey, the current national chief of the Congress of Aboriginal Peoples, who was there with Harry Daniels when they first filed the court action.

Dorey said he and Harry Daniels talked about the action for years prior over coffee or maybe a “pint of beer.”

“Harry was the godfather of my only daughter … it’s a proud day for me and Gabriel,” said Dorey.

It may be a whirlwind of a day for Gabriel Daniels, but his mind keeps going back to one thing.

“I’m really proud of my father,” he said.