Trina Roache

APTN National News

RAIDS AND RECONCILIATION

Provincial governments have to find a role within treaty in order for us to have any sense of reconciliation in the country.”

On December 15, 2015, Canada’s Prime Minister Justin Trudeau stood on a stage in Ottawa and talked about reconciliation for Indigenous people in Canada.

Treaty expert Niigaan Sinclair was there to watch his father Justice Murray Sinclair, present six years of work as a Truth and Reconciliation Commission commissioner.

The TRC released its full report with 94 recommendations, calling on Canada to “renew or establish Treaty relationships.”

Sinclair recounts the optimism he felt on that day watching an emotional Trudeau take part.

“The man smudged. I saw it. I was right there,” said Sinclair. “I think he’s very open to a relationship and to an engagement on these issues.”

But Sinclair said that’s not enough.

“Provincial governments have to find a role within treaty in order for us to have any sense of reconciliation in the country.”

Sinclair said that discord is evidenced by what happened thousands of kilometres away, in Manitoba, on the same day as the TRC event on Ottawa.

There was no courtesy to make a phone to call to the Government of Pine Creek First Nation in Treaty 4 Territory.”

Watch Part 1 of Treaty Rights

There was no call. No heads up. Just a number of RCMP vehicles, Conservation officers and a police K-9 unit.

That’s what Chief Charlie Boucher remembers about Dec. 15, 2015, as Prime Minister Trudeau was speaking in Ottawa.

Boucher said his treaty rights were violated that day on the Pine Creek First Nation in Manitoba.

According to the search warrant, authorities were looking for evidence he’d been hunting moose in Saskatchewan.

Boucher, and Christina Cook, an Anishinaabe lawyer based in Winnipeg, are still trying to figure out why.

“That’s just it. We don’t know,” said Cook. “Really? You can execute a search warrant and not tell us why?”

Ten days earlier, Boucher, his nephew George Lamirande and a few others from Pine Creek, took down a couple of moose on Crown land in Saskatchewan.

At the time, Boucher had a nasty run-in with a local farmer.

“Right away, he was very negative,” said Boucher. “Saying, ‘well, don’t you have enough, you Indians?’ I always practice my rights in the best way. And he alleged other things, like, ‘you guys are always over-harvesting.’ What? Again, it’s not appropriate actions and comments and statements by the farmer. He should have phoned the authorities.”

From what happened next, it’s clear what the farmer did.

“I got a phone call from Chief Boucher while I was driving down the street,” said Cook, recounting the confusion over what was happening. “He said, ‘I haven’t been charged but there was a search warrant executed on my house.’ I said, ‘For what?’”

Boucher didn’t know. He told her they were looking for guns but didn’t find anything. He sent her a copy of the search warrant.

“And what’s interesting about the search warrant is that it was applied for in Saskatchewan, endorsed in a Manitoba court, and it was executed by the RCMP,” said Cook. “And again, Chief Boucher and the Pine Creek First Nation government was not advised or told that the RCMP would be rolling in with lights flashing and a K-9 unit.”

The only warning Boucher had, was from a community member who had seen Saskatchewan conservation trucks traveling in a line of RCMP cars, heading toward Pine Creek.

“I looked at the search warrant and of course I’m going to comply,” said Boucher. “But I told the officer, this is wrong you should have at least gave me the courtesy to give me a call as chief of Pine Creek First Nation.”

The officers also carried out a search at the house of Boucher’s nephew George Lamirande. The officers took frozen meat from the freezer, though Lamirande said it wasn’t moose meat from Saskatchewan.

“And now the Province of Saskatchewan is DNA testing the moose,” said an unimpressed Cook. “Really? Really? How much money are you going to spend prosecuting the Indians? Really. No seriously, it’s insane. This is, best case scenario, a misunderstanding between neighbors. We can’t figure out this issue in a better way on a nation-to-nation or government-to-government dialogue than DNA testing a moose, and three RCMP vehicles and K-9 unit?”

The irony that the raid was carried out on the same the prime minister was talking reconciliation isn’t lost on anyone from Pine Creek.

“The Liberals are using a lot of really colourful rhetoric. Empowerment rhetoric,” said Derek Nepinak, grand chief of the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs (AMC). “It’s nice to hear, but you know, what happens in the colourful ballrooms of Ottawa is a far cry from what’s happening in the bushes around here when we come up against conservation officers that are pointing their guns at us. “

Before Nepinak took on the AMC leadership, he was chief here in Pine Creek. “I was shocked to hear that this was happening in my community.”

Nepinak calls Saskatchewan’s handling of the raid “an abuse of power and authority.”

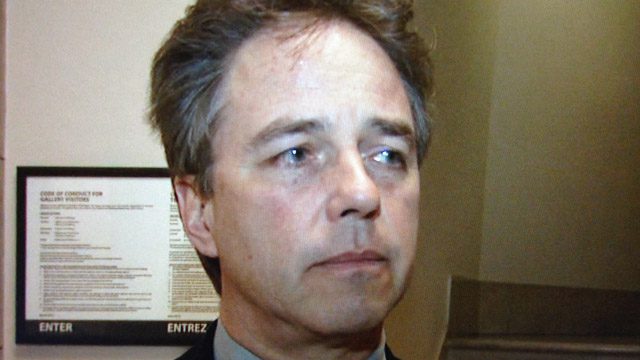

With the case still under investigation, Premier Brad Wall won’t comment on specifics.

“But I’ll just answer hypothetically,” Wall told reporters in January. “Treaty rights don’t trump certain provincial provisions that allow provinces to manage the conservation issue as we would all want. They also don’t trump private property. We respect treaty rights, but there are certain things treaty rights do not trump when it comes to hunting. And we’ll let that information come forward and let this process play out.”

It’s been nearly three months since the raid and there are still no clear answers.

But there are a lot of questions.

“This issue around treaties has to be dealt with because we have ignorant leaders who are saying things like treaty rights do no trump provincial jurisdictions,” said Niigaan Sinclair. “There is nothing more wrong than that.”

THE LINE ON TREATY

To me there’s no border. There may be to the province, but for us that understand treaty, like I said, my treaty is portable. I can go anywhere.”

“There’s always boundaries,” said Boucher. “No hunting signs. Fences. There were no fences before.”

Chief Charlie Boucher rides a skidoo back to the family hunting cabin of George Moosetail, a band councillor in Pine Creek.

It’s a half hour trek along a winding path in the woods, cutting across flat fields of snow, and skirting farm land.

Moosetail said he feels like traditional Anishinaabe lands are shrinking.

The hunting cabin has become a refuge.

“It’s like all we got as Anishinaabe people,” said Moosetail. “This is the only place I can come out to hunt where I feel safe … it’s our own little sacred place to come.”

When asked what that means for his treaty rights, Moosetail pauses before answering, “Treaty to me is a white man’s word. I see us as all Anishinaabe – Treaty 1, Treaty 2, Treaty 4…I see us all as one.”

Those borders matter to government.

Watch Part 2 of Treaty Rights

Last November, Ed Hayden, a former chief of the Roseau River First Nation in southern Manitoba, went hunting in Saskatchewan.

He was respecting a ban on moose hunting in his province. Over-hunting, disease and predators have led to a drop in the population.

“To me there’s no border,” said Hayden. “There may be to the province, but for us that understand treaty, like I said, my treaty is portable. I can go anywhere.”

So he left Treaty No. 1, along with a few other Anishinaabe hunters, and took down three moose on Crown land in Saskatchewan.

Conservation officers arrived shortly after and told him he couldn’t hunt there because he “didn’t belong in this treaty area.”

Hayden was given a warning for “Unlawfully hunting. Exercising treaty rights where not recognized.”

The warning said to look “into Saskatchewan treaty rights before hunting in the province.” Conservation officers told him to bone the animals right there in the field.

“So we spent over three hours doing that,” said Hayden. “Taking the meat off the bones and then we left.”

Hayden’s story highlights a discord between Indigenous and provincial understandings of treaty rights.

“The spirit and the intent of the right to hunt and fish for the purposes of livelihood and cultural survival, cultural continuance, is not tied to border,” said Niigaan Sinclair.

Sinclair heads the Native Studies Department at the University of Manitoba. He teaches treaties in class. He lives it, having grown up in Treaty No. 1. Sinclair wears it on his skin.

He rolls up his sleeve and traces the lines of a tattoo on his forearm. A map of the traditional clans that live along the Red River and signed the Selkirk Treaty in 1817; the first in Manitoba.

A series of eleven Numbered Treaties cover parts of what is now Ontario and the Prairie provinces.

In 1930, Canada formally handed over jurisdiction to Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba through the Natural Resources Transfer Act.

The provinces were given responsibility over lands, resources, education – key aspects that affect the daily lives of Indigenous peoples.

“And so the provinces say, well this is our control because this is our territory,” said Sinclair. “And Indigenous peoples would say well, we never ceased those rights. We only have relationships with the Crown in order to ensure these things that we have our hunting and fishing territories, our own ways of life; that we continue on forever.”

The lines on a modern-day map overlay traditional lands and treaty areas established in the making of Canada.

A Lesson on Treaties

For Pine Creek Chief Charlie Boucher, who lives in Treaty 4, the provincial border cuts through his territory.

But it’s not a cut-off line for treaty rights.

In a phone interview, Saskatchewan’s Assistant Deputy Minister for Environment Kevin Murphy agreed.

His government recognizes the rights of any First Nation with a Numbered Treaty that overlaps the border. That includes Pine Creek in Manitoba.

So though Murphy won’t comment on an ongoing investigation, Chief Boucher was within his rights to harvest moose in Saskatchewan as long as he was on unoccupied Crown land, or had permission from a private landowner.

But Ed Hayden, according to the province’s view on treaty rights, was not.

“If the treaty does not overlap our jurisdiction then we don’t honour the treaty rights within our jurisdiction and that’s according to case law,” said Murphy.

Indigenous leaders take issue with that.

“What’s happened since they created those boundaries is that they acquired with it a false sense of authority over Anishinaabe people,” said Grand Chief Derek Nepinak. “But they bring it through the use of force. Because they’ll bring their guns right into your house.”

Nepinak was recently in Pine Creek to meet with Boucher, who’s been trying hard to drum up attention and action over what he views as violation of treaty rights.

Charlie Boucher said it’s bigger than the raid on his house by Saskatchewan conservation officers.

Here in Manitoba, Boucher wants to sit at the table with the province. He wants a say in how resources are managed.

“Treaty. Treaty basis. A Crown relationship. Anishinaabek,” said Boucher, emphatically. “Like I said, we never abandoned our sovereignty. We want to relate in a good way, in a proactive way with Manitoba and Saskatchewan.”

Last fall, Boucher sent a letter to the province asking for a meeting to talk about co-management.

He didn’t get a response.

But in an interview with APTN National News, Conservation Minister Tom Nevakshonoff was open to the idea.

“I would be very interested in working with the various chief and councils around the province to work specifically on co-management endeavors,” said Nevakshonoff. “That makes total sense to me. Ultimately, the responsibility of the department is the preservation of the species. That’s what comes first.”

When it comes to protecting the environment, Boucher says Indigenous people and Manitoba Conservation are on the same side.

Though sometimes, it doesn’t feel that way.

STRAINED RELATIONS

It’s exacerbating and amplifying poverty and isolation by having these trucks even seized for a year, eighteen months. Manitoba needs to do what other provinces do. They need to make this automatic forfeiture discretionary.”

Indigenous leaders and lawyers use the words ‘adversarial’ and ‘strained’ to describe the relationship between Indigenous hunters and conservation officers.

Anishinaabe hunters talk about feeling bullied and harassed, including Chief Charlie Boucher.

“Trucks up ahead of me. Conservation is stopping everybody.” Boucher explains a typical encounter. “Conservation comes and looks in each of the trucks. I’m in the fifth truck, well, they come and talk to me first.”

Watch Treaty Part 3

Boucher has hunted for 50 years. He offers tobacco and shares the meat with his community. But he feels targeted when he out in the bush.

“My treaty card is what they look for,” he said.

Some of the conflict arises when Indigenous people hunt in ways that regulated hunters can’t.

Treaty people don’t have to follow the same set of provincial regulations.

It might vary from province to province, but generally there’s no bag limit, or seasonal restrictions. And Indigenous people can hunt at night with lights, a controversial practice called “spotlighting.”

But an Aboriginal treaty right upheld by the Supreme Court of Canada in 2006.

Two men from the Saanich Nation in British Columbia argued the Tsartlip people had practiced night hunting since time immemorial. Though times had changed, and rifles and spotlights took the place of bows and arrows and torches.

The Supreme Court steered away from a blanket sanction on night hunting, adding it’s not a treaty right to do so dangerously.

There are limitations on treaty rights that the province can regulate. The Manitoba hunting guide outlines the rules that apply for First Nation hunters in general. No shooting a firearm from a public road or highway. No selling the meat. But for spotlighting, the limitations are vague; don’t “discharge a rifle or shotgun at night where it is dangerous to do so.” But it has to be on Crown land.

George Moosetail, a band councillor on the Pine creek First Nation in Manitoba, went hunting one night in January.

He wanted to harvest deer meat for an elder in his community.

He took APTN National News on a ride to show what happened.

Moosetail asked his friend Jason to drive us.

On a snowy back road lit up only by the truck’s headlights, he motions for his friend Jason to slow down.

“Okay, this is where I stopped right here,” said Moosetail. “This is that little strip of private land I was telling you guys about.”

Except Moosetail didn’t see any sign indicating it was private property. He also didn’t see conservation trucks parked close by.

“They probably could’ve stopped us from shooting if they knew we were on private land,” he said. “But to us it was Crown land. Our land. Our traditional hunting grounds.”

But Moosetail was mistaken. Crown land was still a five minute drive down the road.

Conservation officers charged him with spotlighting and his truck was seized.

In February, he went to court and pleaded guilty.

Moosetail’s case is just one of several on the desk of Anishinaabe lawyer Christina Cook.

She’s had other cases recently where the charges of spotlighting are questionable.

In one case, hunters with an unloaded gun in the backseat of the car, shining a light to look for Crown land, which is often unmarked.

“Really?” said an unimpressed Cook. “Make shining a light illegal if that’s going to the case.”

A big issue Cook is fighting in court are the penalties for hunting at night.

Manitoba Conservation automatically seizes any meat, hunting gear and vehicles. Even if the owner of the truck is not hunting.

Cook said she’s had cases where she’s won in court, but even with an acquittal, the hunter was without his truck for months.

The penalty is meant to deter poachers from spotlighting.

But Cook said there’s no discretion with the law. And the loss of a truck is felt deeply in remote Indigenous communities.

“These people’s livelihoods are on the line. You have a $40,000 truck for somebody who makes $16,000 a year, that’s huge, that’s the biggest asset they’re ever going to have and their credit is ruined. So these are high stakes,” said Cook.

She tells stories of a client who was about to lose his job because he lost his truck, though he hadn’t been the one hunting. Zealous Crown attorneys that pursue hunting charges like criminal cases and clients who won in court, but the bill for the two day trial rang in at $10,000, and legal aid doesn’t cover the costs.

Cook is torn over these cases. She grew up in BrokenHead Ojibway Nation in Manitoba.

She’s proud to take on cases involving Aboriginal and treaty rights, but…

“These people are poor. They need help and there’s very limited ways that I can help them.” Cook paused, and then admitted, “It’s depressing. It’s depressing for them and for me.”

Cook called the truck seizures unfair and wants the law changed.

“It’s exacerbating and amplifying poverty and isolation by having these trucks even seized for a year, eighteen months,” she said. But forfeited? Manitoba needs to do what other provinces do. They need to make this automatic forfeiture discretionary.”

Though the circumstances around the penalty may vary, the province’s position is clear.

Conservation Minister Tom Nevakshonoff said government recognizes the Aboriginal right to hunt and fish for food, but safety is a foremost concern.

“If people break the law in the course of their activities then they are subject to penalty,” said Nevakshonoff. “And hunting illegally, we discourage to the utmost degree and seizure of vehicles is part of that.”

As for complaints from Indigenous hunters of harassment by conservation officers, the Minister was surprised to hear the question.

“I can’t speak to specific incidents unless it’s brought specifically to my attention,” said Nevakshonoff. “I know that our staff are doing their utmost to do their jobs in the field but they’re also fully aware of First Nation rights.”

Moosetail lost the truck he was driving. When he pleaded guilty, he paid a $1,200 fine. But still no truck.

When Chief Boucher called a meeting in Pine Creek to talk about hunting issues, Moosetail shared his story.

It goes beyond the charge for spotlighting. He’s frustrated with the strained relations between Anishinaabe hunters and conservation officers.

“I’m getting sick and tired of getting pushed. We always have to prove it’s our land,” said Moosetail. “Growing up, I always hunted at night, spotlighting on a quad where I don’t have to see a farmer. Like you’re going out stealing … and you’ve got to go farther, you know? ‘Cause we’re in a swamp.”

When Moosetail finished talking, people nodded their heads in agreement. The elders shook his hand. Many there had been on the receiving end of meat he’s harvested.

Grand Chief Derek Nepinak sat and listened and believes their stories are a sign of a much larger problem.

“It’s about all those men and women over the years, my own family included in this, that have been raided by these people coming into our homes, going through our freezers and taking meat,” said Nephinak. “For no reason other than to bully and harass and try and scare our people off the land.”

And that cultural connection to the land is vital to Indigenous people. Treaty rights are a practical, tangible way of putting healthy food on the table. Food security is a major issue facing indigenous people in Canada.

Nepinak draws the lines very clearly.

“There’s a direct correlation between the strong armed tactics of government to keep us confined within our reserves and the rise in diabetes in our communities,” said Nepinak. “We’re suffering. We’re not thriving. And people need to wake up to that.”

FROM TREATY TO THE TABLE …

If we’re not pulling the moose meat from the bush, then we’re getting sick off the processed foods and that’s exactly what’s happening.”

The high cost of foods has made headlines in northern Inuit communities. But food security is an issue for Indigenous communities throughout Canada. An Aboriginal Peoples Survey by Statistics Canada in 2012 links it to poverty and poor health.

More than a quarter of First Nations people are obese which has lead to a diabetes epidemic.

In Manitoba specifically, one out of four Indigenous people living off reserve struggle to feed themselves.

There’s little data for communities on reserve, but Indigenous leaders like AMC Grand Chief Derek Nepinak said food security is a major concern.

“If we’re not out there trapping, the fur bearers, if we’re not pulling the fish from the lake if were not pulling the moose meat from the bush, then we’re getting sick off the processed foods and that’s exactly what’s happening,” said Nepinak.

Nepinak used to be chief of the Pine Creek First Nation.

He said one of the best things he did was bring the bison back home. The community has a herd, though it’s too small to harvest right now.

Pine Creek band councillor George Moosetail checks on the bison, standing among them as he throws down a bucket of grain.

“Very proud, very spiritual animals,” said Moosetail. “I come out here when I need advice. When I feel like I’m stuck and I have no one to talk to. I come and offer tobacco.”

Moosetail doesn’t look to the bison for food. He says the impressive beasts already made their sacrifice.

“They gave themselves, the bison, to the Anishinaabe people for their clothes. To keep warm. For tools,” said Moosetail.

It’s estimated that the Prairies were home to millions of bison prior to European settlement.

By the 19th century, over-hunting brought the animal close to extinction.

As Canada looked to expand west, the kill-off of bison was a purposeful means to control Indigenous nations by starving them out.

Treaty expert Niigaan Sinclair says what was then the District of Saskatchewan led the resistance to the treaty making process.

“Food or the withholding of food has had a long history in Saskatchewan,” said Sinclair. “At the end of 1880s, people in Saskatchewan are starving so they’re being forced to sign treaties and forced to move to the Southeast part of the region by the federal government in order to make way for the train line.”

Given the history, Sinclair isn’t surprised at recent issues Indigenous hunters from Manitoba have faced when they cross the provincial border.

Saskatchewan Conservation officers raided the home of a Pine Creek Chief Charlie Boucher, looking for moose meat and rifles.

And Ed Hayden, from Manitoba’s Roseau River First Nation in Treaty 1, was given a warning for hunting where “treaty rights not recognized.”

Hayden was respecting a ban on moose hunting in Manitoba. Because his treaty rights are portable, he went to Saskatchewan. He was hunting to provide meat for the food bank in his community.

The provincial government’s trying to regulate First Nation’s access to traditional foods and how we exercise our treaty rights, our inherent rights. It furthers the problems our people have with their diets.”

Roseau River has started the Community Freezer Program as a way to make sure people can put food on the table.

Volunteer Regina Atkinson Southwind counts names on a list. Close to 80 people were on it the day Hayden went hunting last November. Behind her, a shelf is stocked with cans of soup and boxes of pasta.

The good stuff is kept in the freezer.

“We want to provide traditional foods,” said Southwind. “So we have the deer meat, moose meat, we have someone donating fish.”

Most people in the community don’t hunt or fish anymore. They don’t have the knowledge or resources to do it.

“All these attempts by the government in the past to limit how our people, to assimilate our people into their society,” said Southwind, “We don’t know how to take care of ourselves how we used to, you know?”

Southwind said that loss of connection to the land has had a big impact on health.

“The provincial government’s trying to regulate First Nation’s access to traditional foods and how we exercise our treaty rights, our inherent rights,” said Southwind. “It furthers the problems our people have with their diets. Diabetes, cancer and having too much processed food.”

The food bank relies on hunters like Hayden to fill the freezer. Despite the warning from a Saskatchewan conservation officer, he’ll go back.

But Hayden has big questions. For provincial governments. For Canada. For Indigenous leaders.

“My question is,” asked Hayden. “What are you going to do to protect our Treaty rights to hunting?”

THE PATH FORWARD

We have federal and provincial leaders in major decision making positions that have little to no knowledge of treaty. If there’s a blemish in this country, it’s that.”

Niigaan Sinclair was recently talking treaties to his class at the University of Manitoba where he heads the Native Studies department. A wide range of ages and faces, many Indigenous, fill the stadium seats.

It’s a class Canadian politicians should pay attention to. Sinclair is critical of government’s take on treaties. A recent raid on a chief’s house by conservation officers looking for moose meat has raised questions around jurisdiction.

And highlights what Sinclair calls an “epidemic of ignorance.”

“It is a complete condemnation on the education that we have federal and provincial leaders in major decision making positions that have little to no knowledge of treaty,” said Sinclair. “If there’s a blemish in this country, it’s that.”

Education on Aboriginal, Métis and Inuit history, culture and treaties is a key step toward reconciliation.

Optimism among Indigenous leaders soared since the Liberals won the last federal election and the new language coming from the prime minister is of respect and nation-to-nation relationships.

Sinclair was in Ottawa for the release of the full report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

“If you look at what Trudeau said on that day,” said Sinclair. “The man smudged. I saw it. I was right there. I think he’s very open to a relationship and to an engagement on these issues. But then he goes up on stage and the first thing that he says, ‘my teacher never taught me anything to do with Indigenous people. He taught me nothing.’”

To hear the prime minister admit he knew little about the country’s Indigenous peoples stuck in Sinclair mind.

“It’s a real indication of how much profound ignorance there is in this country about Canadians not understanding what it means to be Canadian,” said Sinclair. “Because to be Canadian is to be a treaty person.”

In Saskatchewan, government officials won’t comment on why conservation officers crossed the border into Manitoba, and then came on to the Pine Creek First Nation, unannounced, to raid Chief Boucher’s house.

But Assistant Deputy Minister for Environment Kevin Murphy said the province does offer Aboriginal awareness training for employees. He said the department “insists upon it” for those working in conservation and resource allocation.

The province was handed jurisdiction over lands two decades after it joined Canada in 1905.

In the 1930 Natural Resources Transfer Act, the federal government handed control over resources to the three Prairie provinces.

Murphy said treaty rights are “preeminent,” but conservation and regulation of hunting, fishing, and trapping are left to the province.

“The province has a hierarchy of recognition rights,” said Murphy. “Conservation of the resource is our primary objective. Recognition of inherent and treaty right of First Nations and Metis Peoples comes second. Regulated hunting and user groups are below that level in terms of our allocation policy.”

It’s a priority list Indigenous leaders take issue with and raises the potential for conflict over competing views on the law of the land.

“It’s all about their system,” said Chief Charlie Boucher. “Their laws they implemented without our consent. I obeyed provincial law. When are they going to obey our original law?”

There’s a fundamental difference in the language used by Indigenous people and government when it comes to land, to treaties. Boucher talks about a connection to the land that’s not based on ownership. Sinclair explains that, instead, Indigenous own the “relationships with the land.”

Derek Nepinak sets the bar for treaty rights as “the expression of freedom to the land,” but one that gets whittled down by government regulations.

Names like Sparrow, Corbierre, Marshall and Tsilhqo’ten headline key decisions by the Supreme Court of Canada that uphold Aboriginal and treaty rights.

“But at the same time,” said Sinclair, “the federal government needs to stop this continual march to the Supreme Court involving this issue and really take a leadership role in being able to rectify and engage and recognize that rights are a fundamental part of the country.”

The language the new Liberal government is using around reconciliation, respect and nation-to-nation relationships might not be enough.

Sinclair said it’s a refreshing mindset, but one at odds with the machinations of government.

“Canada is invested in continually wanting to get out of the Indian business,” he said. “And that’s what the Indian act is intended to do.”

Sinclair calls treaties a ‘one-off’ for government; a historical agreement used to gain access to land whereas “if we look at those treaty documents, they were intended to be about the future not the past.”

Indigenous people are unlikely to be the ones to walk away from the treaty table.

“We are capable people. We are willing people,” said Boucher. “We want to relate in a beautiful way.”

The chief was to pin down expansive issues like reconciliation in a tangible way. In the long-term, he’s talking co-management of resources.

For today, he wants answers on why Saskatchewan conservation officers raided his house after he went moose hunting in that province. He wants to know what can be done about hunters feeling bullied and harassed by game wardens in Manitoba.

It’s why he brought in the Grand Chief of the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs to meet with the community recently.

And Derek Nepinak wants details.

“All the people that have had their vehicles confiscated or their rifles confiscated. We’re going to need to talk to you all,” he told everyone.

As for a response to the raid, Nephinak is gearing up for a battle. “We have brilliant minds, experts in Canadian law who can punch holes right through Mr. Wall’s political rhetoric and his failure to respect treaty rights and we plan on bringing the fight to him.”

What that fight looks like is still unclear.

Sinclair said the framework is already there. “If we look at those treaty documents they were intended to be about the future not the past.”

Boucher wants to work with government and says, if it’s about the environment, then they’re on the same page.

So that reconciliation can begin on the ground.