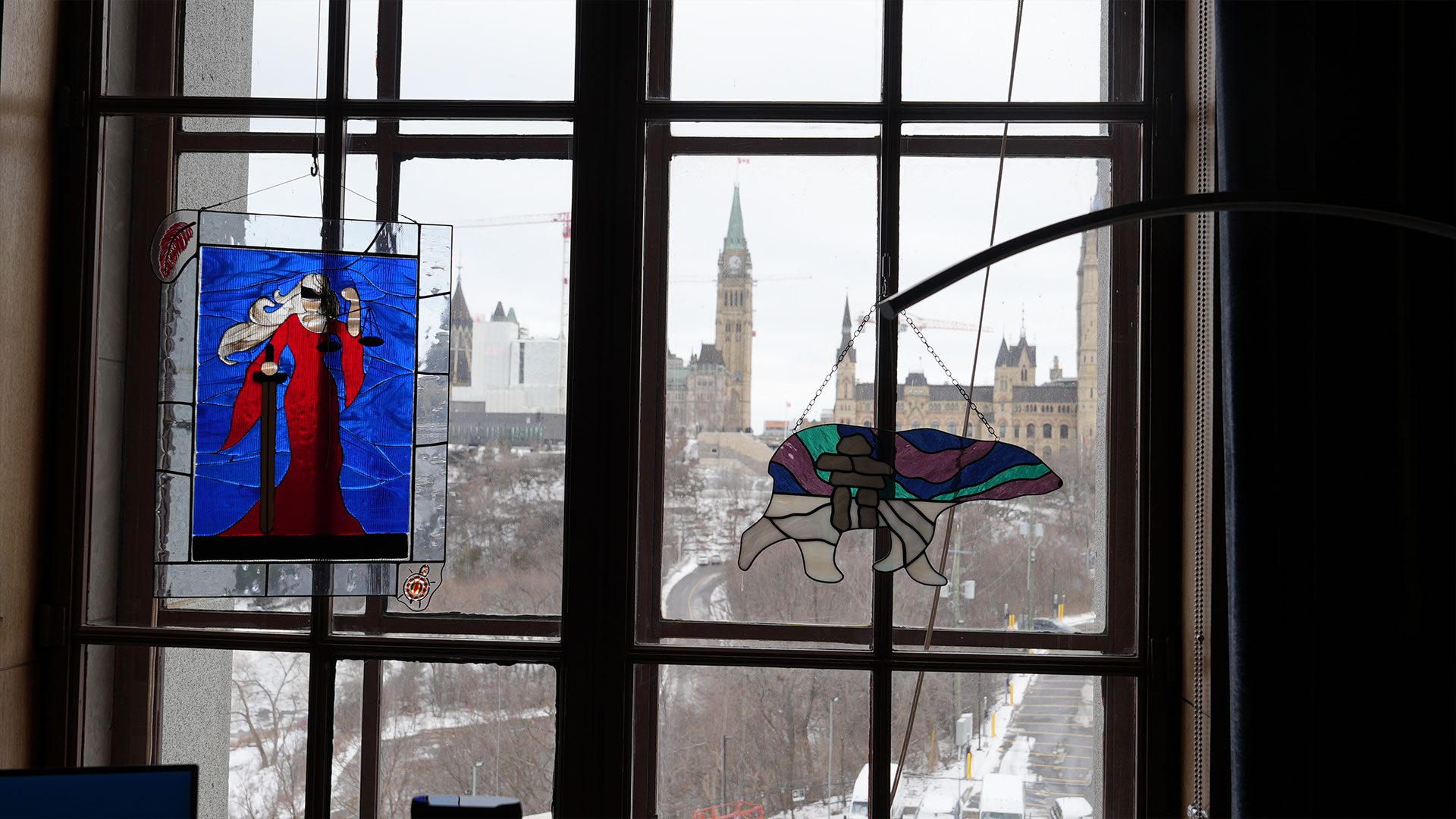

When the Supreme Court is in session, you’ll find Justice Michelle O’Bonsawin behind her desk in a small wood-panelled office at the court on Wellington St. just west of Parliament Hill by 7 a.m.

The day consists of several meetings. It may start with a consult with her three clerks who help disseminate thousands of pages of documents and then a gathering with other justices who sit on the high court. At noon, a lunch meeting with a clerk working on a particular file.

In the afternoon, more meetings. Likely a working dinner and then home by 10 p.m.

“I found in the first year it was more difficult because I felt the weight of it on my shoulders,” said O’Bonsawin, adding that she understands how much adversity First Nations, Inuit, and Métis have faced throughout history.

“As time moved forward, I find it’s easier. I could do just the best that I can always give 100 per cent, trying to be mindful of my role in the court, how I interact with my colleagues, how we work together on files.”

O’Bonsawin grew up in a French-speaking family in northern Ontario but her roots are Abenaki from the Odanak First Nation in Quebec.

Since her appointment to the high court in September 2022, she said her goal has always been to “be the best judge that I can be and to hopefully contribute to Canada by writing good solid decisions,” O’Bonsawin told Face to Face guest host Tiar Wheatle.

“I think having a different perspective. It’s something that’s unique through lived experience as an Indigenous person,” she said. “I think a lot of people want to see themselves reflected when they’re looking at the bench and who’s sitting there.

“So, if an Indigenous person or any other, not typical white Anglo-Sax, and person appears in front of the court, they know that there is someone up there that has a perspective that is not your typical colonized perspective, I guess is how I would put it.”

O’Bonsawin joined the Canadian Bar Association and the Ontario Bar Association in 2000. She is also a long-standing member of the Indigenous Bar Association.

In 2017, former justice minister and attorney general Jody Wilson-Raybould appointed her to the Ontario Superior Court. She said while on the bench, there was a moment that “really stood out.”

“Then president Trump had made a comment with regard to a [U.S.] senator [Elizabeth Warren] who he had referred to as Pocahontas. And the next day when I was sitting in court, I had a series of different lawyers appearing in front of me on motions. At one point, in the crowd that are sitting there waiting to be heard, I hear one lawyer say to another, ‘oh yes, she is Native Indian, she is our Pocahontas of the North,’” O’Bonsawin said.

“And she said it loud enough for me sitting over 20 feet away to be able to hear what she had said. When it came time for those two lawyers to come and appear in front of me, I actually said for the record, I’ve just been referred to as Pocahontas of the North and it’s not appropriate.”

O’Bonsawin said she raised her concerns with the lawyer’s law firm and later, received a letter of apology, “It basically said ‘I apologize for your perception of what I said in a private conversation to a colleague which was highly inappropriate.’ I didn’t accept the letter of apology,” she said.

While the comment was made by a senior lawyer, a junior lawyer who was present came in person to apologize which she said “took guts.”

“The day in question when I got home I took the time to talk to my kids about this, who are much younger, because I wanted them to realize that it doesn’t matter what level you are in society, discrimination it could happen to anybody and no one is shielded from that situation and what’s important is how you respond to it. You have to say something and speak up because just having remain silent, it just perpetuates the problem.”

History of Gladue Reports within The Criminal Code of Canada

In 1993, the federal government, recognizing the First Nation, Inuit and Métis Peoples were being sentenced to prison time in high numbers, introduced an amendment to the Criminal Code. Section 718. 2(e) calls for judges to consider “all available sanctions, other than imprisonment, that are reasonable in the circumstances and consistent with the harm done to victims or to the community should be considered for all offenders, with particular attention to the circumstances of Aboriginal offenders.”

Most say the provision has not worked in the three decades since it was introduced. According to the Office of the Correctional Investigator, First Nation, Inuit and Métis women make up nearly 50 per cent of the prison population, on the men’s side, it’s 32 per cent.

Former Supreme Court justice Beverly McLachlin asked O’Bonsawin to write an article on Gladue. The high court has called the overincarceration of Indigenous Peoples a “crisis” and a “sad and pressing social problem.”

“We must also take judicial notice of the history of colonialism, displacement, and residential schools in Canada, and how that history translates into lower educational attainment, lower incomes, higher unemployment, higher rates of substance abuse and suicide, and higher levels of incarceration for Indigenous persons,” O’Bonsawin wrote in her 2020 article, We All Have a Role to Play: Gladue Reports.

“A Gladue report is not just a sentencing report: it is often the first step in an Indigenous person’s healing.”

The term Gladue report comes from a 1999 Supreme Court ruling involving a woman by the name of Jamie Tannis Gladue who was convicted of manslaughter.

The high court ruled that the trial judge did not take into consideration her Indigenous heritage and experience when sentencing her. From then, the phrase Gladue Principles was born – a set of guidelines that lawyers and the judges need to abide by when dealing with Indigenous offenders.

Part of the process includes what is called a Gladue report – a detailed history of the offender’s past. The goal is the inform the court on a person’s past throughout the trial. The problem, these Gladue principles are used in a haphazard way across the country.

“It’s really hard because what happens is there is no general certification across Canada for Gladue writers so, at times, you will have those that are writing cookie cutter reports, you will have those that have had more training, have gone into the communities, met with community workers, Elders, family members to really get that individualized information with regard to the Indigenous accused,” O’Bonsawin told Wheatle in the F2F interview.

“So because there is no uniformity it is really difficult. The consistency of report writing varies in regions. For Ontario for example, in Toronto, there is Aboriginal Legal Services. They do the majority of all the reports here [Ontario] so there is consistency on that front. And unfortunately some courts are not really referring to 718.2(e) of the criminal code which is that mandatory provision for sentencing the Indigenous accused and looking at the Gladue principles.”

Supreme court cases, the Abenaki language, and the legacy of the O’Bonsawin name

While Wilson-Raybould appointed O’Bonsawin to the Ontario Superior Court, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau who gave her the nod to sit on the high court.

On Nov. 28, 2022, O’Bonsawin, with family and members of the Odanak community on hand, was sworn in.

“My journey to this court hasn’t been an easy one but it has been meaningful and rewarding,” O’Bonsawin said at her swearing-in ceremony. “I hope that my journey to this court will inspire young women to pursue their dreams. I am a big believer that if you have a goal, work hard and never give up you can make things happen and achieve those dreams. Our actions are reflections of ourselves. We must be proud of who we are and of our uniqueness,” she said.

“I’m grateful to my ancestors for giving me wisdom today.”

There’s been no shortage of cases involving Indigenous issues before the court since her swearing-in.

“I’ve been really fortunate because there has been a variety of interesting cases since I arrived. As many are aware, we have really big Indigenous law cases with C-92 child protection, with Restoule, we have had really interesting criminal law cases, some civil cases out of Quebec, so it’s been an amazing two plus years. The amount of work is, it’s big, it’s continual. A lot of reading, a lot of writing,” O’Bonsawin said to Wheatle.

The court also heard the residency case involving Cindy Dickson while O’Bonsawin has been on the bench.

“I always say I am in a pre-arranged marriage with eight other people that I haven’t chosen so it’s been a good experience,” said O’Bonsawin. “We all have different lived backgrounds, we have different personalities, we are fortunate we get along because sometimes that may not always be the case when you look at a big composition of a court.”

After 28 months of working together, O’Bonsawin said in a jokingly tone, the nine justices have become like their own little family.

“But you know there is give and take, and sometimes like every family, we don’t always see eye to eye but generally I think that it’s a well meshed group of nine judges,” she said. As for her own family lineage, O’Bonsawin says they moved from Abenaki home in the mid-1800s to farm in northern Ontario.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, she said she started to learn the Abenaki language – and is writing a chapter on her family’s history for a book about Odanak.

In the Abenaki language, O’Bonsawin translates to ‘pathfinder’ in English.

While O’Bonsawin has paved a path for herself in the legal system, she’s never forgot about the struggle of her father and his family. So when she was asked in the spring of 2023 if she would be willing to have a school named after her in Toronto, she found herself a bit overwhelmed.

“When I was first approached by the school board they asked me if they could put my name forward and I remember telling my family I couldn’t believe it. I said can you believe they want to possibly put my name on a school which was a huge surprise to me because that is normally for someone who is deceased in my mind,” O’Bonsawin said.

After about a six-month process, O’Bonsawin said she learned they chose her name. In September 2023, École secondaire Michelle-O’Bonsawinin opened its doors.

“It’s a really proud moment for, especially my father, because when he was young, they were called the little savages of Sunnybrae, a lot of discrimination,” she said.

“His name, it was difficult to pronounce, people didn’t know how to do so and for him to see his name on a high school last year was a very proud moment for him but also for me and my relatives.”