Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) says it can’t tell the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal when it will be able to clear a massive backlog of Jordan’s Principle cases from its collective desk.

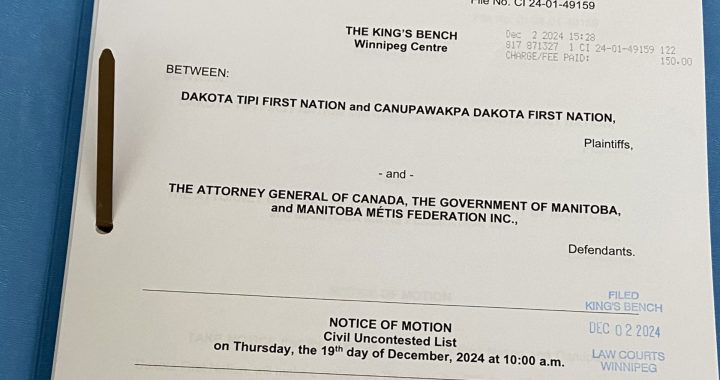

“At this time, and taking into account the unpredictable number of new daily requests, ISC is unable to estimate the timeframe in which all backlogged requests will be cleared,” said a Dec. 10 letter from federal lawyer Dayna Anderson to tribunal chair Sophie Marchildon.

“However, we anticipate that via Tribunal-assisted mediation, the parties will co-develop solutions to reduce and eventually eliminate the backlogged requests.”

The letter was posted online by the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society (Caring Society).

Last month, the Tribunal ordered Canada to submit a detailed plan on how to clear its Jordan’s Principle cases. According to the government, the backlog sits at 140,000 including “approximately 25,000 self-identified urgent cases.”

The cases are individual requests for “products, services and supports” from First Nations families.

The government argued in its letter that responding to the Tribunal’s order to “review, triage and reclassify the backlog” by Dec. 10, while still answering new requests “would have required diverting significant resources from other ISC essential programs.”

“This would jeopardize the overall delivery of services to Indigenous Peoples across Canada within ISC’s mandate,” it said.

However, Cindy Blackstock, executive director of the Caring Society, had no sympathy for the government.

“They have to pay their bills on time, so families aren’t left out of pocket and nations (aren’t left out of pocket),” she said. “They have to deal with the backlog.

“And the backlog is just a code word for saying that children’s requests have gone unanswered by the department. So they have to deal with that as a matter of immediacy.”

The Jordan’s Principle program was implemented after Parliament passed a motion in 2007. It’s named after Jordan River Anderson, a boy with numerous health needs from Norway House Cree Nation, who was stuck in a Winnipeg hospital while the provincial and federal governments argued over who would pay for his care at home.

He died in hospital.

The program stipulates that when a request for help comes in, the first jurisdiction pays and then works out the reimbursement later.

Jordan’s Principle at the Tribunal

The program was part of a discrimination complaint launched against the federal government in 2007 by the Caring Society and Assembly of First Nations (AFN) that also included on reserve child welfare.

It accused the government of using a narrow description to define a Jordan’s Principle case.

According to the government’s website, the original program focused on “jurisdictional disputes involving First Nations children living on reserve with multiple disabilities” like Jordan Anderson, who required “services from multiple service providers.”

The Tribunal eventually ordered the government to expand the program to services including respite care, wheelchairs and ramps, educational and transportation supports, specialists.

The federal government, however, has faced dozens of non-compliance motions.

Then in its Nov. 21 ruling, the Tribunal said that “life-threatening cases” and “cases involving end-of-life/palliative care, risk of suicide, risk to physical safety, no access to basic necessities (the Tribunal orders that this must be defined by the parties as part of their consultations on objective criteria to be used to identify urgent Jordan’s Principle requests), or risk of entering the child welfare system are urgent.”

“The Tribunal has also been clear that the “time-sensitive nature” of a case could also make it urgent. Some life-threatening situations may require immediate response and while others may require a timely response.”

Paying for Jordan’s Principle

During last week’s AFN gathering in Ottawa, chiefs from Manitoba took Ottawa to task for not upholding Jordan’s Principle. The Keewatin Tribal Council in Manitoba said it ran up $7 to $8 million in debt before the government finally reimbursed them.

Howard Burston, executive director of the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs, said communities in Manitoba “still haven’t received any additional funding.

“The current issue that we do have right now is that many First Nations organizations, such as the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs’ Jordan’s Principal Service Delivery Unit, are in deficit because they’ve been told to spend, spend, spend.”

Other jurisdictions have similar complaints.

The government said it is working on the backlog now.

“ISC has immediately reassigned existing Jordan’s Principle resources to a surge team to focus on urgent requests, to the degree that ISC is able to do so without adversely impacting other services to Indigenous communities across Canada,” the government said in its letter.

The government noted it would consider a Tribunal direction to co-develop “criteria for urgency” to include “criteria and guidelines for cases involving no access to basic necessities, cases involving caregivers and children fleeing from domestic violence, and the criteria for qualified professionals.”

The government has several deadlines coming up at the Tribunal in January.

With files from Karyn Pugliese