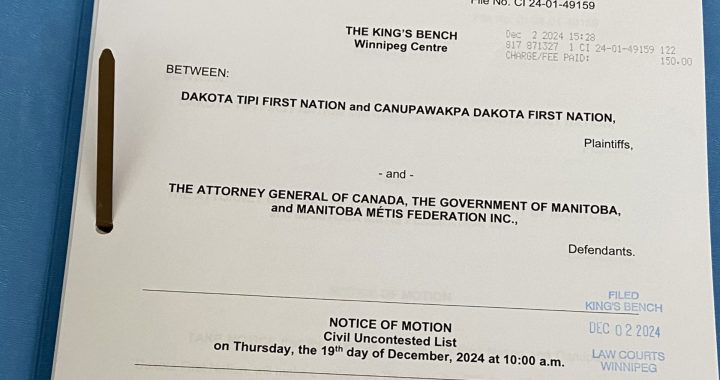

Dexter Adams, 84, of Pasqua First Nation had his braids cut off Photo: Kathleen Crowe

A Cree doctor based in Edmonton says the nurse responsible for cutting off an elderly First Nations man’s braids at Royal Alexandra hospital in the city should be fired and charged with assault.

Dr. James Makokis says systemic racism is embedded in Canada’s healthcare system and only strong action will change people’s behavior.

“When you are touched with violence or in an unwanted way, that is a form of assault,” Makokis told APTN News. “What I think might be helpful is for families and the health system itself is to take an approach that uses the justice system in instances like this and charging workers with assault.

“There needs to be policies and procedures with consequences for those who don’t follow them. Providing cultural safety training or seminars on the cultural significance of hair is not going to stop this from happening. There needs to be built in policies and procedures that protect every person’s bodily autonomy within the health system.”

Makokis is responding to the story of Dexter Adams, 84, originally from Pasqua First Nation in Saskatchewan. His family says his braids were cut off by a nurse while he was at the hospital. His niece says the family also found his eagle feather and bear grease, used to keep his hair tangle free, had been thrown in the garbage.

Many Indigenous people in Canada express their identity and spirituality with their hair. Braided hair is considered a symbol of strength and honours ancestors who were not allowed to have braided hair in residential schools.

Dexter’s niece, Kathleen Crowe, recalls the shock when she walked into the hospital room and saw Dexter’s braids had been cut off.

“Shock, tears, anger-it was just a really wide-range of emotions to see that,” Crowe told APTN.

She says she too was curious about whether cutting her uncle’s hair qualifies as an assault.

“Out of curiosity I called Edmonton Police Service non-emergency line to inquire about it,” Crowe said. “I was advised that given that my uncle’s hair was not cut for medical reasons, EPS would have to investigate further with the hospital to determine whether they would press charges or not, which means that my aunt would need to call back to the non-emergency complaint line to request a service call,” Crowe said.

She hasn’t discussed the issue with her aunt yet, but the family is calling for cultural competency training for hospital staff.

But Makokis says training alone won’t help.

“You can’t train yourself out of systemic racism, and that’s the core issue. The health system needs to look within to find out why these things keep happening,” Makokis said. “We can have all the commissions in the world. We’ve had the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples – we’ve had all of these things to look at these problems, yet all of these years they continue to happen.

Makokis says the internal investigations the hospitals and AHS do never restore balance to the family or patient that’s been harmed.

“They never provide an adequate answer or response with regard to what is going to happen to the person that caused the harm, as we’ve seen in this case,” Makokis added.

Makokis said as troubling as the story is, it’s not surprising.

“Obviously I was angry as an Indigenous person who also has braids. I wasn’t surprised. These are just incidences where the family was courageous and brave enough to come forward,” Makokis said.

Makokis said health professional education programs have to have anti-racist training embedded in them. But he says you need to go further and look at how physicians and nurses are dealt with in these cases.

“How do the regulatory bodies that provide the licenses for regulated health professions like physicians and nurses actually investigate incidents like this? And how do they have the opportunity to change the way the regulated health professionals practice?”

First hand experience

As a family medicine resident in 2010 at the University of British Columbia in Victoria, Makokis said he was working in the obstetrics and gynecology unit delivering babies, when he experienced racism himself.

“When I went to go deliver a baby, a nurse pulled on my braid to stop me from going to deliver the baby. She seemed to think that was an acceptable way to stop me,” Makokis said.

Adams was deemed a high-risk for falling during the spring, and was on a wait list for long term care because his wife could no longer care for him at home.

Eve Adams, his wife, was herself undergoing chemotherapy treatment for stage four lung cancer and living in Métis housing in Edmonton.

“After his hair was cut, there was a really noticeable change in him, like he lost his will to live,” said Crowe.

Crowe says they were told by the hospital that the nurse involved had asked her uncle for permission to cut his hair and he gave it. However, Crowe said her uncle had dementia and the hospital was aware that decisions regarding his care were to be made by his wife.

Adams’ hair was cut on Mar. 23. Crowe said he passed away five weeks later on May 6.

“We believe it was having his hair cut that shortened his life,” Crowe says.

While the family is not considering a lawsuit, it sought hospital records to find out what happened. Crowe says they received 3 weeks of nurses notes during the period her uncle was in hospital. The notes had been redacted around the time his hair was cut.

Meanwhile, Crowe says the family has not received an apology for the nurse’s actions.

AHS provided a statement on what happened to Dexter Adams. It claims that it met with and apologized to the family. APTN verified with the family that an apology hasn’t happened. The statement says, however, that AHS policies require informed consent from the patient and family before cutting hair – even for medical purposes.

The statement says an investigation will take place but the results will be confidential.

Incidents such as this one prompted Edmonton Henday NDP MLA Brooks Arcand-Paul to introduce a private members bill this year. He says Bill 209 is intended to hold the Government accountable for its responsibilities to reconciliation.

“Our hospitals are overloaded with patients with wait times through the roof and for a nurse to have gone ahead with something like this when I assume there were many other patients needing assistance is really egregious,” Arcand-Paul says.

“It really makes me wonder if the cultural competency training they’re (supposed to get) is even getting done.”

The bill, which passed first reading on Nov. 4, would require the Alberta government to commit to advancing reconciliation through the delivery of its programs and services. It would also require the government to act transparently on the calls to action by establishing and reporting on specific measures it’s taking toward reconciliation.

Métis Elder’s hair cut at Saskatchewan hospital

This is not the first time an Indigenous person’s hair has been cut while in hospital in recent memory.

In August, Métis Elder Ruben St. Charles fell and was sent to the Royal University Hospital in Saskatoon by ambulance.

St. Charles, 73, had fractured his hip. He told APTN in October that he passed out because of the pain and when he woke up in the hospital, he noticed something was missing.

“I felt my ponytail, no hair,” he said.

When a nurse entered his room he asked, “What the hell happened to my hair?” he said. “They said, ‘We’ll tell you later.’”

St. Charles said they never did explain what happened.

He said he had a small ponytail that was intended to be cut only if he lost his sister. St. Charles never did get any answers. He eventually received an apology.

Read More

Crowe says ongoing training needs to be provided to staff working in hospitals.

“If you look at call to action #24 (of the National Truth and Reconciliation Commission report) it calls upon medical and nursing schools to provide training,” Crowe says.

The call to action reads:

“We call upon medical and nursing schools in Canada to require all students to take a course dealing with Aboriginal health issues, including the history and legacy of residential schools, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Treaties and Aboriginal rights, and Indigenous teachings and practices. This will require skills-based training in intercultural competency, conflict resolution, human rights, and anti-racism.”

The website indigenouswatchdog.org lists this call to action as “In Progress” as of Nov. 30, 2024.

In September, the Canadian Medical Association apologized to Indigenous peoples for the harms done to them.

Dr. Joss Reimer, CMA president said in issuing the apology: “We have not lived up to the ethical standards the medical profession is expected to uphold to ensure the highest standard of care is provided to patients and trust is fostered in physicians, residents and medical students. We realize we have left Indigenous Peoples out of that high standard of care.”