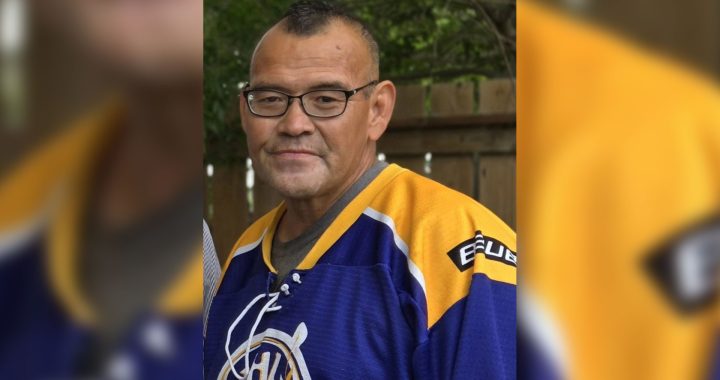

COO Grand Chief Abram Benedict, seen here at the AFN SCA in Ottawa on Dec. 3, was a staunch supporter of the child welfare reform deal. Photo: Mark Blackburn/APTN

First Nations leaders are split over next steps after a landmark $47.8 billion child welfare reform deal with Canada was struck down, prompting differing legal opinions from both sides.

The Assembly of First Nations and a board member of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society have received competing legal opinions on potential ways forward.

Ontario Regional Chief Abram Benedict says the chiefs he represents are still hoping the reform agreement with Ottawa that chiefs outside the province voted down two months ago is not moot. Chiefs in Ontario are interveners in the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal case that led to its realization.

He added there are also concerns that some of the elements in the new negotiation mandate outlined by chiefs in an October assembly go beyond the current governance structure of the Assembly of First Nations.

“There will have to be action by the Assembly of First Nations in the very near future to advance these positions, but you also need willing partners,” Benedict said.

“We’re still considering what our options are.”

Those options are also being debated in legal reviews commissioned by the Assembly of First Nations and a board member of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society, which are both parties to the human rights case, along with Nishnawbe Aski Nation.

Khelsilem, a chairperson from the Squamish Nation who penned a resolution that defeated the deal in October, critiqued the stance of First Nations in Ontario by saying they negotiated a “bad agreement” for First Nations outside the province and now that chiefs want to go back to the table for a better deal, they want to split from the process entirely.

“It potentially undermines the collective unity of First Nations to achieve something that is going to benefit all of us,” he said.

Decades of advocacy

The $47.8 billion agreement was struck in July after decades of advocacy and litigation from First Nations and experts, seeking to redress decades of discrimination against First Nations children who were torn from their families and placed in foster care.

The Canadian Human Rights Tribunal said Canada’s underfunding was discriminatory because it meant kids living on reserve were given fewer services than those living off reserves, and tasked Canada with reaching an agreement with First Nations to reform the system.

The agreement was meant to cover 10 years of funding for First Nations to take control of their own child welfare services from the federal government.

Chiefs and service providers critiqued the deal for months, saying it didn’t go far enough to ensure an end to the discrimination. They have also blasted the federal government for what they say is its failure to consult with First Nations in negotiations, and for the exclusion of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society, which helped launched the initial human rights complaint.

In October at a special chiefs assembly in Calgary, the deal was struck down through two resolutions.

The Assembly of First Nations sought a legal review of those resolutions by Fasken Martineau DuMoulin LLP — a firm where the former national chief of the organization, Perry Bellegarde, works as a special adviser.

In the legal review from Fasken, it appears as though the assembly asked for direction on how to get “rid” of two resolutions used to vote down the deal, with an employee of the firm saying they can review the resolutions together if they want them both gone, or they can “leave room for compromise” with one of the resolutions.

In a statement, the Assembly of First Nations said the review was conducted to access the legal, technical and operational aspects of the resolutions to ensure their “effective implementation.”

“The opinions formed by external counsel are their own and do not reflect the views or positions of the AFN,” said Andrew Bisson, the chief executive officer, who added it’s not unusual for the organization to seek such reviews.

Address the language

Bisson did not address the language used by a Fasken employee to “get rid” of resolutions, but said “the legal and technical reviews were conducted in good faith, not to undermine the Chiefs’ direction. The Chiefs have provided clear direction, and the AFN is committed to following that direction.”

The legal reviews from Fasken, dated Nov. 15, argue that the October resolutions on child welfare require a significant review of who voted for them, along with changes to the organization’s charter should they be implemented.

Resolution 60 called for a rejection of the final settlement agreement, and for the establishment of a Children’s Chiefs Commission that will be representative of all regions and negotiate long-term reforms. It also called for the AFN’s executive committee to “unconditionally include” the Caring Society in negotiations.

Fasken said that commission is contrary to the AFN’s charter, and the law, because the AFN’s executive committee doesn’t have the power to create one, and that the executive committee “alone” has the authority to execute mandates on behalf of the assembly. It adds there are no accountability measures for the new negotiation body, and that it will represent regions that are not participants in the AFN.

Resolution 61, which built upon resolution 60, is similarly against the charter for the same reasons, the review says. As such, it says, the resolutions can’t be implemented.

The firm also wrote that there were alleged conflicts of interest during the October vote, saying “numerous proxies were also employees, shareholders, directors, agents or otherwise had a vested interest” in the First Nations child and family service agencies whose interests were the subject of the resolutions voted the deal down.

Chief Joe Miskokomon of Chippewas of the Thames First Nation in southwestern Ontario called that “political deception.”

In response to that review, a board member of the Caring Society, which has been a vocal critic of the July deal, sought their own.

The review

The review penned by Aird Berlis for Mary Teegee and dated as Dec. 2, stated it was “inappropriate for the AFN to seek, and not disclose, legal opinions which are then cited to attempt to second-guess decisions already made by the First Nations in Assembly.”

It also states that while the AFN’s vice president of strategic policy and integration, Amber Potts, raised concerns with the movers and seconders of the resolutions, the entirety of the legal opinion the assembly sought was not shared with them.

Teegee’s review challenges that of the AFN’s by saying the resolutions are consistent with the AFN’s charter, and that nothing restricts First Nations in Assembly from expressing their sovereign will by delegating authority to another entity.

“AFN’s role and purpose at all times is to effect the sovereign will of First Nations, however it is expressed, on ‘any matter’ that they see fit,” the review from Aird Berlis reads.

“It is too late to attempt to question the resolutions. They are now final.”

With files from the Canadian Press