Clarence Woodhouse waits for a Senate justice committee hearing to begin in Ottawa. Photo: Mark Blackburn/APTN

Clarence Woodhouse was rendered speechless in the Senate Thursday by the lack of an Ojibwe interpreter – 50 years after being wrongly convicted in Manitoba on a false confession in English.

Sen. Brent Cotter apologized to the Anishinabe man, who was exonerated on a 1974 murder conviction earlier this month, for not having a “qualified translator” ready.

Woodhouse sat mutely as his fellow exonerees Brian Anderson, a former co-accused also from Pinaymootang First Nation, and Guy Paul Morin, of Ontario, shared their wrongful conviction experiences with the Senate Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs.

The committee is reviewing Bill C-40, an amendment to Canada’s Criminal Code that would create a new Miscarriage of Justice Review Commission Act.

The act, also known as David and Joyce Milgaard’s Law, would, among other things, create an independent body to review wrongful convictions as “expeditiously as possible”. Presently, applications are reviewed by lawyers under the justice minister in a process that takes between 20 months and six years, the committee heard.

The senate committee needs to give the bill, which has already been approved by a majority of MPs, third and final reading to make it law.

“It took 50 years to prove my innocence,” Anderson told the senators in Ottawa. “That is time I cannot get back.

“I’m almost 70 years old.”

Anderson, who was exonerated in 2023, was 18 when he says Winnipeg police officers coerced him into signing a false statement in the 1973 murder of a restaurant chef.

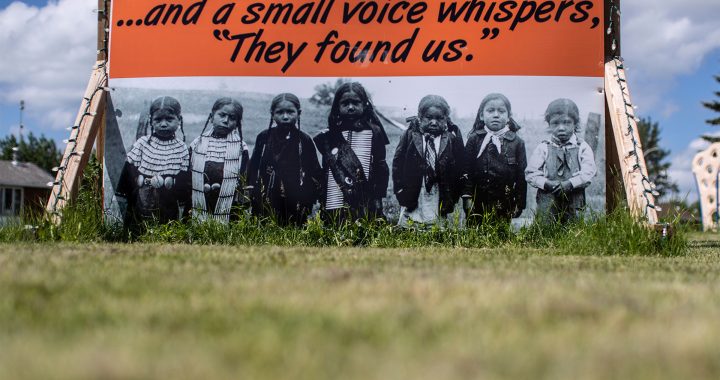

Woodhouse, now 72, also supposedly confessed to the killing in fluent English, despite primarily speaking Ojibwe or Saulteaux. He said the White judge and jury didn’t believe he was intimidated by Winnipeg police officers.

Woodhouse, Anderson and two other co-accused, one of whom has since died, said they were in the city 50 years ago looking for work when they were arrested and charged. They are now suing all three levels of government for damages, citing racism and intimidation by police and alleged collusion between the police and Crown prosecutor.

Their confessions were entirely manufactured by police detectives, a Crown prosecutor told their acquittal hearings.

“None of us had ever been in trouble with the criminal justice system,” Anderson told the senate committee. “When we were brought in for questioning, we didn’t know what was happening.

“English was not our first language … I only spoke my language which is Ojibwe.”

The senators gave the men a standing ovation for their at-times emotional statements about being wrongly convicted and sentenced to life in prison.

“The police took advantage of our young age and unknowing of the criminal justice system,” added Anderson, 69, “and the fact we were Anishinaabe and did not speak English well.”

Anderson was released on parole in 1987, but wasn’t acquitted until last year after then-federal justice minister David Lametti ordered a new trial.

Lametti, now a private lawyer in Quebec, and former prime minister Kim Campbell also addressed the senate committee Thursday.

They said it was time Canada had a similar commission to those in the UK, New Zealand and Norway staffed by former judges and lawyers to process potential wrongful convictions in what has been heard would be a faster and more streamlined way.

Campbell, also a former justice minister, said systemic racism, tunnel vision, unconscious bias and police coercion have long been faulted for miscarriages of justice, but it was people who made those errors.

People, she noted, who needed training from and exposure to the opinions and experiences of diverse professionals who should be part of the new commission.

Arif Virani, the current justice minister, appeared before the committee on Wednesday.

“This legislation will change lives,” Virani told senators. “An independent commission for reviewing potential miscarriages of justice will rescue innocent, wrongfully convicted people who are unfairly stuck in prison.”

He noted it would be better for victims of crime as well, because it would correct errors along with wrongful convictions.

“Bringing them one step closer to actual justice,” he added.

Virani acknowledged the system, which operates as a slowly moving ministerial review process now, fails to adequately address wrongful convictions.

He said it doesn’t help women, Indigenous Peoples and Black Canadians “in the same proportion as they are represented in Canada’s prisons.”

An Indigenous adult may represent five per cent of the Canadian population, but Virani said “you represent 33 per cent of admissions to federal custody.”

Woodhouse, as one of those statistics, said he would submit a statement about his wrongful convction in Ojibwe for the committee to translate.

He was 21 when he was convicted of second-degree murder.