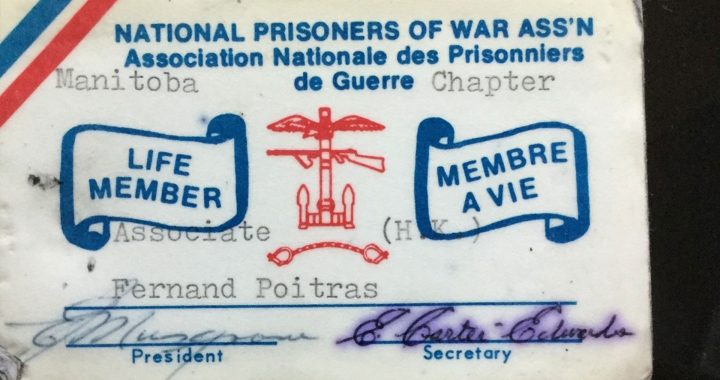

A photo released by Athabasca Chipewyan Chief Allan Adam after his arrest in 2020.

It’s been four years since Athabasca Chipewyan Chief Allan Adam was tackled to the ground in a violent altercation with members of the Fort McMurray RCMP but the case is still open, according to Alberta’s police watchdog.

Adam was at a casino in Fort McMurray in March 2020 when he was confronted by RCMP about an expired licence plate.

A 12-minute video was released from the dash-cam of an RCMP vehicle that recorded the arrest.

About seven minutes into the video sirens can be heard and an agitated Adams can be seen getting out of his vehicle.

Out of the left side of the screen, an officer runs into Adams, tackling him to the ground. It appears that Adam is pinned face down during the struggle.

The officer appears to strike Adam with his right hand during the arrest. Getting Adams in handcuffs and up off the ground takes nearly three minutes.

The chief’s face is bloodied as they lead him to the RCMP vehicle.

The arrest made news across the country.

Later, the Mounties said the arrest was conducted according to RCMP guidelines.

Because Adam sustained injuries, the Alberta Serious Incident Response Team (ASIRT), the police watchdog, was called in. After four years, the case remains open.

Adam tells APTN News he got a call from ASIRT about five months ago, asking if he still wants to press charges but he had nothing more to say.

APTN reached out to ASIRT for comment. A media spokesperson said Adam’s case remains under review by the executive director.

The lengthy delay in Adam’s case may mean an Alberta MLA’s hope for a swift and “effective” investigation into the recent shooting death of Hoss Lightning, a 15-year-old boy from Samson Cree Nation, may not come to pass.

“Justice is the most important thing that should happen in this case and every case moving forward,” said Brooks Arcand-Paul, an NDP MLA in Edmonton, on Monday,” and we would just want ASIRT to move effectively and expeditiously so that the Samson Cree Nation and the family of Hoss Lightning can have some answers that they so desperately need right now.”

Read More:

Video shows RCMP arrest of Athabasca Chipewyan chief

Lightning died after calling 911 in Wetaskiwin, Alta., 72 kilometres south of Edmonton.

RCMP said they received a report early Friday morning about a boy who called 911 and told a dispatcher he was being followed by people trying to kill him.

About an hour later, police said officers found the teen with several weapons, which they confiscated.

Police said a confrontation then led to two officers shooting the boy, who died later in hospital.

The confrontation, the police said, was captured by dash cam video located in the officers’ cruisers.

Arcand-Paul also told APTN the Crown prosecutorial service needs to make sure to follow through with recommendations that come from ASIRT investigations.

But a criminal justice professor says there are “layers of problems” with police watchdog agencies in Canada, and some problems unique to ASIRT.

Kevin Walby is a professor at the University of Winnipeg and director of the Centre for Access to Information and Justice (CAIJ).

Walby says delays in investigations of officer-involved incidents seem to be more common in Alberta. Walby thinks that’s due to a number of factors.

“A lot of times people don’t believe that police watchdogs are actually being as vigorous as they could be in these investigations or they’re not undertaking investigations sometimes because their allegiances are with the police who are alleged to have engaged in some kind of malfeasance,” says Walby.

According to Walby, there’s a persistent belief by the public in the “blue wall.”

“There’s a saying in criminology and criminal justice studies, the police blue wall of silence and there’s a lot of corruption, a lot of malfeasance that goes on behind the blue wall, and police in their subculture are encouraged to keep quiet about it. So, when you have the same people who were raised in that sub-culture and then they go and work for ASIRT, people legitimately ask “are they still behind the blue wall?”

Walby says the executive director of ASIRT has come out several times saying they are under-staffed and under-resourced. Walby doesn’t dispute that ASIRT needs more resources.

“If they’re running a crew of four or five investigators and there’s four or five police shootings every week, that’s why there is a backlog.”

According to data on ASIRT’s website, it has investigated 536 cases since 2015, resulting in an average of four officers being charged per year for the same period.

Walby said that cases not being investigated or investigated in a timely manner, and the outcome of court cases is leading to further distrust of police and the justice system.

“If you widen the lens and you look at the way the criminal justice system treats Indigenous people whether First Nations, Métis or Inuit people in Canada, nothing has changed. Since we’ve had the Royal Commission (on Aboriginal Peoples), nothing has changed since we’ve had various provincial inquiries-probably a dozen now, that specifically note the systemic discrimination, the brutality and the racism Indigenous people face from various criminal justice players, nothing has changed and seems to be getting worse.”

Family and community members in Samson Cree said goodbye to Lightning during a vigil Saturday and a memorial walk on Sunday.