Warning: This story contains distressing details about residential schools

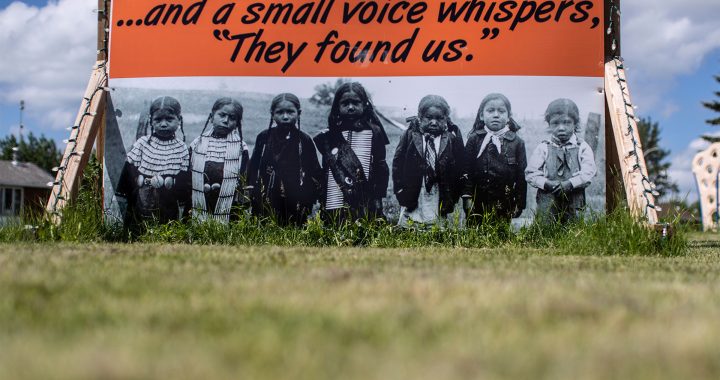

A new report shows the residential school system used Indigenous children as grave-diggers, guinea pigs in an experimental community, and even brides and grooms.

Sites of Truth, Site of Conscience is a 256-page deep dive into the “assimilationist policies” of the system by Kimberly Murray, the special interlocutor for missing children and unmarked burials.

Murray says she detailed how an estimated 150,000 First Nations, Inuit and Métis children were exploited and abused as a way to help counter denialism about the intent and impact of residential schools.

And, to show the callous attitude toward their lives and deaths.

“Exposing these records, as painful as it is to read them, is integral to upholding the right of Survivors, Indigenous families, and communities to know the truth about what happened to the missing and disappeared children,” the report says.

“It is also a powerful antidote to denialism and will help Canadians to understand why truth, accountability, justice, and reparations are essential to reconciliation.”

Murray has called on Parliament to enact a law against the denial of historical facts and trauma associated with the government institutions that operated between 1831 and 1996.

The report is difficult to read and seems to pick up where the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) left off in 2015.

Murray, whose term ends in 2024, is still expected to produce a final report with recommendations on how best to deal with the unmarked graves and undocumented children communities are discovering while searching former school sites.

“Through both their actions and failures to act, the government and church entities created the crisis of missing and disappeared children and unmarked burials that survivors, Indigenous families, and communities are facing today,” the report says.

“These are important truths that Canada and the churches must accept.”

But to understand the graves, the report shows one has to first understand the sweeping powers government, school and church officials has over the children who were forcibly separated from their families and communities.

Murray says the children literally became the property of the residential school system.

They were used as workers on farms, paired up in arranged marriages, and even sent to live in an experimental community in Saskatchewan.

“The File Hills Colony experiment was intended to further assimilate First Nations people,” the report says.

“Officially established in 1901 on land that was part of the Peepeekisis Reserve, the File Hills Colony was ‘a showcase settlement of … married industrial school graduates, isolated from the older Indians, whom officials feared could cause those discharged from Indian Residential Schools to return to their own cultures’.”

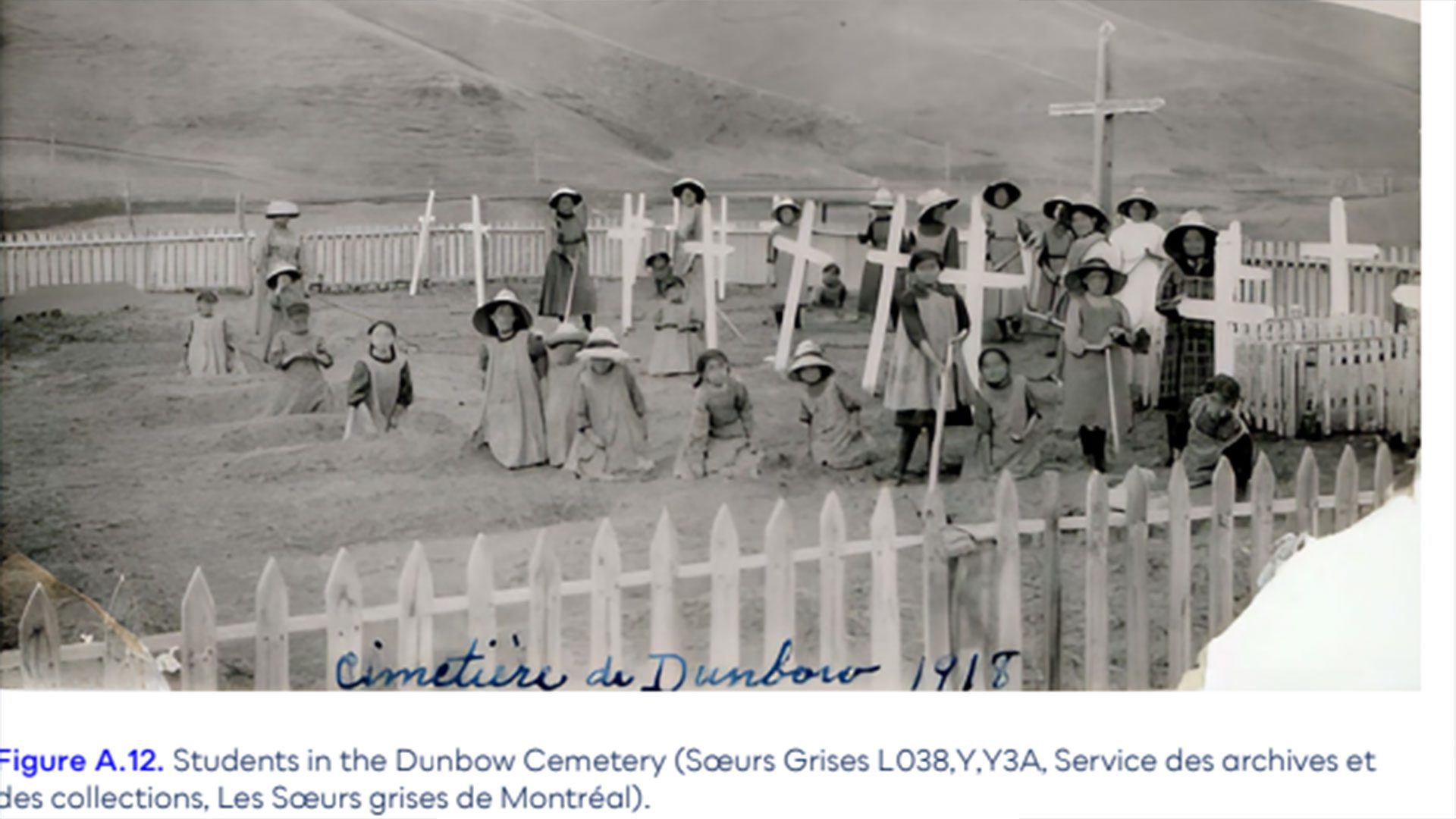

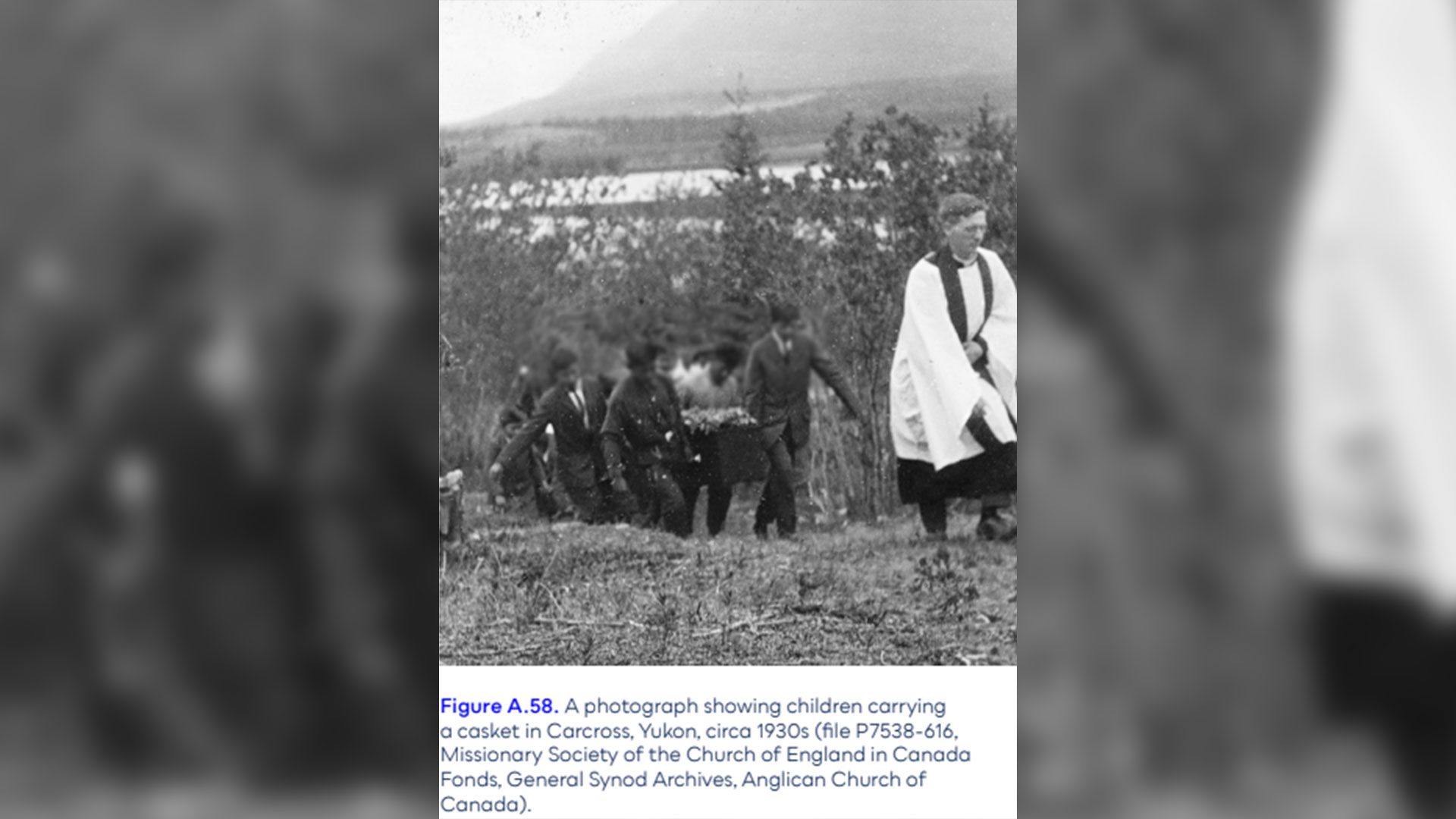

The report says children of all ages “were trafficked” to perform manual labour, including digging graves, as part of the “Working Out” or “Outing” System devideid by Indian Boarding Schools in the United States.

“They were forced to live and work in homes, on farms, and in businesses. Their work placements were always brokered by Indian Agents and the principals of the institutions.”

The ones who were paid had to turn it over to the schools to subsidize the costs of their room and board, the report noted.

‘Rescue centres’

Female students who became pregnant were sent to “rescue centres” for unwed mothers known as “Good Shepherd Homes” – where they were forced to earn their keep in the laundry.

Some who didn’t get pregnant were candidates for men at the File Hills Colony, with “the match, in most cases, having already been arranged before the young people left school … This sort of match-making is encouraged in all the Canadian boarding schools.”

When children died of disease, abuse, neglect or other acts of violence at the schools they were buried in area cemeteries and not sent home, the report says.

Others were transferred, often without parental knowledge or consent … to other institutions “such as Indian hospitals, sanatoria, psychiatric institutes, homes for unwed mothers and delinquent girls, reformatories, juvenile detention centres, penitentiaries, and prisons.

“They often died alone in these institutions without their parents or other family members to comfort them and were buried far away from their homes and communities.”

Help is available through the Indian Residential School Survivors Society’s Crisis Support Line at 1-800-721-0066 and the 24-hour National Indian Residential School Crisis Line at 1-866-925-4419.