The head of the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs says she is looking for answers and guarantees from Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) and Crown Indigenous Relations (CIR) ahead of the federal budget on April 16.

According to departmental plans, $4.1 billion is expected to be cut from ISC beginning in the 2025-26 fiscal year.

“It is unacceptable and irresponsible for the Ministers to unilaterally cut over $4 billion in federal funding when First Nations are already in a constant state of emergency dealing with mental health and addiction crises,” said a statement from Cathy Merrick, grand chief of the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs, a political advocacy organization that represents 62 First Nations in the province.

“Despite assurances from the Ministers that announced cuts would not affect service and program delivery, the AMC stresses that these cuts could not have occurred at a more inconvenient time. Cutting federal funding when so many First Nations already struggle to meet their basic human needs is irresponsible and morally reprehensible.”

According to the government’s website, the ISC budget is scheduled to drop from $20.7 billion for 2024-25 to $16.3 for 2025-26.

“A net decrease in funding for Child and Family Services which is primarily mainly due to sunset (at the end of 2024-25) of funding for implementation reforms to the First Nations Child and Family Services Program; and a net decrease in funding for Jordan’s Principle and the Inuit Child First Initiative which is primarily mainly due to a decrease in core funding for the continued implementation of Jordan’s Principle,” the plan said.

“Decisions on the renewal of the sunset initiatives will be taken in future budgets and reflected in future estimates.”

The plan also shows the department is expected to shed a thousand jobs, from 7,459 in 2024-25 to 6,539 in the 2026-27 fiscal year.

There are concerns that the Jordan’s Principle program is one area that is being cut by the government. The information contained on the government’s website seems to be at odds with comments ISC Minister Patty Hajdu made while on a trip to Whitehorse in February when she said there were “no plans to cut staffing for Jordan’s Principle.”

“As you know, the Department of Indigenous Services also had to look for efficiencies and search for efficiencies but Jordan’s Principle was untouched,” she said on Feb. 23. “In fact, we found those savings in things like legal fees. We’re able to, for example, significantly reduce the cost of legal fees related to the CHRT (Canadian Human Rights Tribunal) final settlement payments.

“Jordan’s Principle, in fact, is undergoing a review right now in general in how we can become more efficient because the claims have grown by 150 per cent just over the last year – which is a good problem to have,” the minister added. “It means kids are getting the care that they need and communities are becoming aware of Jordan’s Principle and are using the program, but it is putting pressure on getting approvals through quickly and we won’t be able to achieve that if we reduce staffing.”

Jordan’s Principle

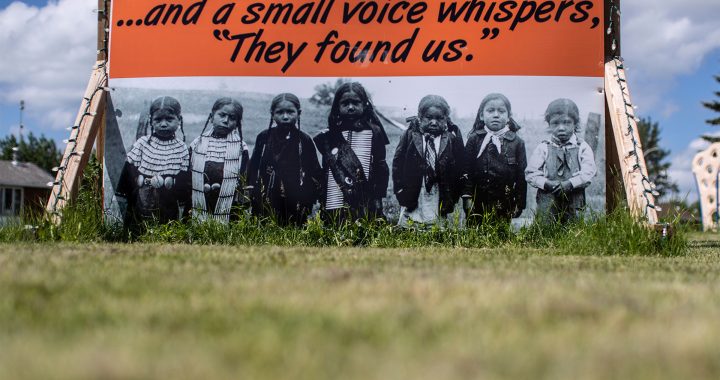

The Jordan’s Principle program is named after Jordan River Anderson of Norway House Cree Nation in Manitoba. Born in 1999 with multiple disabilities, Anderson died at five years old without ever leaving the hospital, after federal and provincial governments couldn’t decide who should pay for his at-home care.

Today, governments claim the plan ensures that “First Nations and Inuit children have access to the products, services and supports they need, when they need them, regardless of where they live in Canada through the Jordan’s Principle and the Inuit Child First Initiative program.”

The House of Commons unanimously adopted a motion to abide by the principle in 2007, but has been accused multiple times of failing to live up to the spirit of the program. In 2017, the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal ordered the government to make changes to comply with Jordan’s Principle, including providing culturally appropriate services and ensuring the child’s best interests are safeguarded.

The principle stipulates that when a child needs health, social or educational services they are to receive them from the government first approached, with questions about final jurisdiction to be worked out afterwards.

Cindy Blackstock, executive director of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society, said a June hearing is scheduled at the CHRT and she intends to prove that, even without the cuts, “Canada is seriously not complying with existing tribunal orders.”

“I welcomed the minister’s statement but I have seen this type of disconnect before,” Blackstock said in an interview, “where Canada, for example, where they said they weren’t fighting First Nations kids in court and they were in court fighting First Nations kids.

“I’m really concerned about what I read in that public accounts statement. We have certainly filed it with the tribunal because now is not the time to be cutting back on Jordan’s Principle when the non-compliance issue is already this serious.”

APTN News reached out to the minister’s office for comment but the response didn’t deal with Hajdu’s February comments and what is contained in the departmental outlook. In part, it said, “We’re targeting operational efficiencies, public servant travels and departmental transformation.”

Meanwhile, concerns are being raised about whether the federal government truly supports the program.

The Keetwatin Tribal Council (KTC), an organization that represents 11 First Nations in northern Manitoba, wrote to Prime Minister Justin Trudeau in February urging his government to respond to the needs of the communities he represents.

KTC said 10,000 people live in the area they represent. In March 2023, the region declared a state of emergency.

“Communities are plagued by an opioid epidemic, chronic underfunding of health care services and inadequate infrastructure,” wrote Grand Chief Walter Wastesicoot on Feb. 22 in a letter he shared with APTN and other media. “This crisis threatens our communities and most tragically, our youth.”

Wastesicoot said, “As we reach the anniversary of the Regional State of Emergency, we find ourselves bridge financing Canada to deliver much needed services. I have been advised by our finance department that Keewatin Tribal Council is now bridge financing seven million dollars under Jordan’s Principle.

“This cannot continue and must be addressed immediately.”

Blackstock said Canada is systematically failing to respond to Jordan’s Principle requests to fund health and social services for children first and deal with who should pay later.

That includes delayed response times to requests for information or assistance in filing a claim, Blackstock said, and, in many cases, extended waits to have claims approved while kids wait.

The allegations are made in two affidavits sent to the CHRT as part of a non-compliance motion the society launched against the federal government for its handling of Jordan’s Principle.

Blackstock said service claims under Jordan’s Principle are taking too long to be processed and requests for assistance from the federal government are taking too long to get a response.

“At Jordan River Anderson’s memorial service, I promised his family that I would do everything I could to ensure that Jordan’s Principle was honoured so that no other child had to suffer as he did,” Blackstock wrote in her 57-page affidavit.

“Eighteen years later, I am still trying to keep that promise.”

Blackstock said the government knows the claims under Jordan’s Principle are piling up and refuses to disclose the size of that backlog.

She said there are significant government delays in responding to Jordan’s Principle calls and in providing reimbursement for services, among other problems.

In some cases, delays approving service mean kids are waiting months to get the care they need.

For instance, the Jordan’s Principle call centre line is supposed to be available around the clock, but it can take hours to get a return call, if one comes at all.

Blackstock said out of 25 times staff members at the Caring Society called the line since January 2023, they were connected to a live agent only twice. When Blackstock was helping families with their calls, some of the issues were only resolved after she contacted the representatives via their non-public emails.

Urgent Jordan’s Principle requests are supposed to be processed within 24 hours. But urgent requests are taking up to one month to be reviewed, according to Independent First Nations, an advocacy body representing a dozen First Nations in Ontario and Quebec.

Blackstock’s affidavit said nearly half the requests made by individuals from those First Nations in 2023-24 are still in review, along with 10 per cent of the files submitted in 2022-23.

The delays extend to the reimbursement of service providers, the Caring Society argued, with ISC missing its own promise to make those payments within 15 days. In 2022-23, the department processed only 50.7 per cent of payments within 15 business days, compared to 82.9 per cent in 2021-22.

The affidavit from Blackstock comes just months after she helped secure a $43-billion child welfare settlement with the federal government for its handling of child welfare and Jordan’s Principle.

With files from the Canadian Press