Lytton 2021 after the wildfire. Photo: APTN file.

A new report from British Columbia’s ombudsperson says emergency support programs for those forced from their homes during the 2021 floods and wildfires are outdated, rely on volunteers working long hours, are inaccessible and not well communicated.

“We have an under-resourced system in place that isn’t meeting the needs of people, many of whom are in the most significant crisis they have ever experienced,” said Jay Chalke the ombudsman for B.C.

Chalke said that support services that are being delivered in Indigenous communities “have to be culturally safe and Indigenous-led.”

This report is based on the 2021 fires and floods in the province. The findings were based on both interviews and questionnaire data collected by the office of the Ombudsperson.

“The province needs to step up, modernize these two programs and put additional resources in place to ensure people are treated fairly and equitably during extreme weather events,” said Chalke at a press conference announcing the release of the report.

The report also found that for Indigenous communities there are additional barriers when it comes to natural disasters.

The ombudsperson office said that extreme weather events are made worse by evacuees who may already be suffering from poverty or difficulty in accessing housing.

Read more:

Residents of the Lytton First Nation in B.C. fled their homes due to wildfire

“Indigenous people are more likely to be disproportionately impacted by displacement as a result of climate change disasters,” reads the report.

The B.C. Ombudsperson report has 20 recommendations, which Chalke said were accepted by the government.

Recommendations included the need to make sure that any disaster program has the ability to process applications and appeals “in a timely manner” and the need to identify better ways to communicate to people who need to access emergency funding.

It also recommended the need for “Indigenous self-determination in emergency management.”

“The province’s work with First Nations and Métis must occur within a rights-based framework, and legislation must be co[1]developed and recognize the fact that First Nations and Métis communities have the experience, skills and knowledge about how to best care for community members,” said the report.

Indigenous residents displaced

At least five major wildfires in B.C caused evacuations during the 2021 fire season and many residents, including First Nations and Métis had to leave their homes for several days if not weeks.

In 2021, the Sparks Lake wildfire burned 95,980 hectares in an area starting approximately 15 km north of Kamloops Lake.

The fire was discovered on June 28, 2021, residents of the Skeetchestn Indian Band and the Thompson-Nicola Regional District were then evacuated. The order remained in place until Aug. 26 when the BC Wildfire Service downgraded the evacuation order.

The Lytton Creek wildfire started on June 30, 2021, and burned 83,671 hectares on the traditional and unceded territories of the Nłeʔkepmx Tmíxʷ, including throughout the Village of Lytton and Lytton First Nation.

Disaster recovery updates from Lytton First Nation indicate that 40 First Nations homes were lost to the fire.

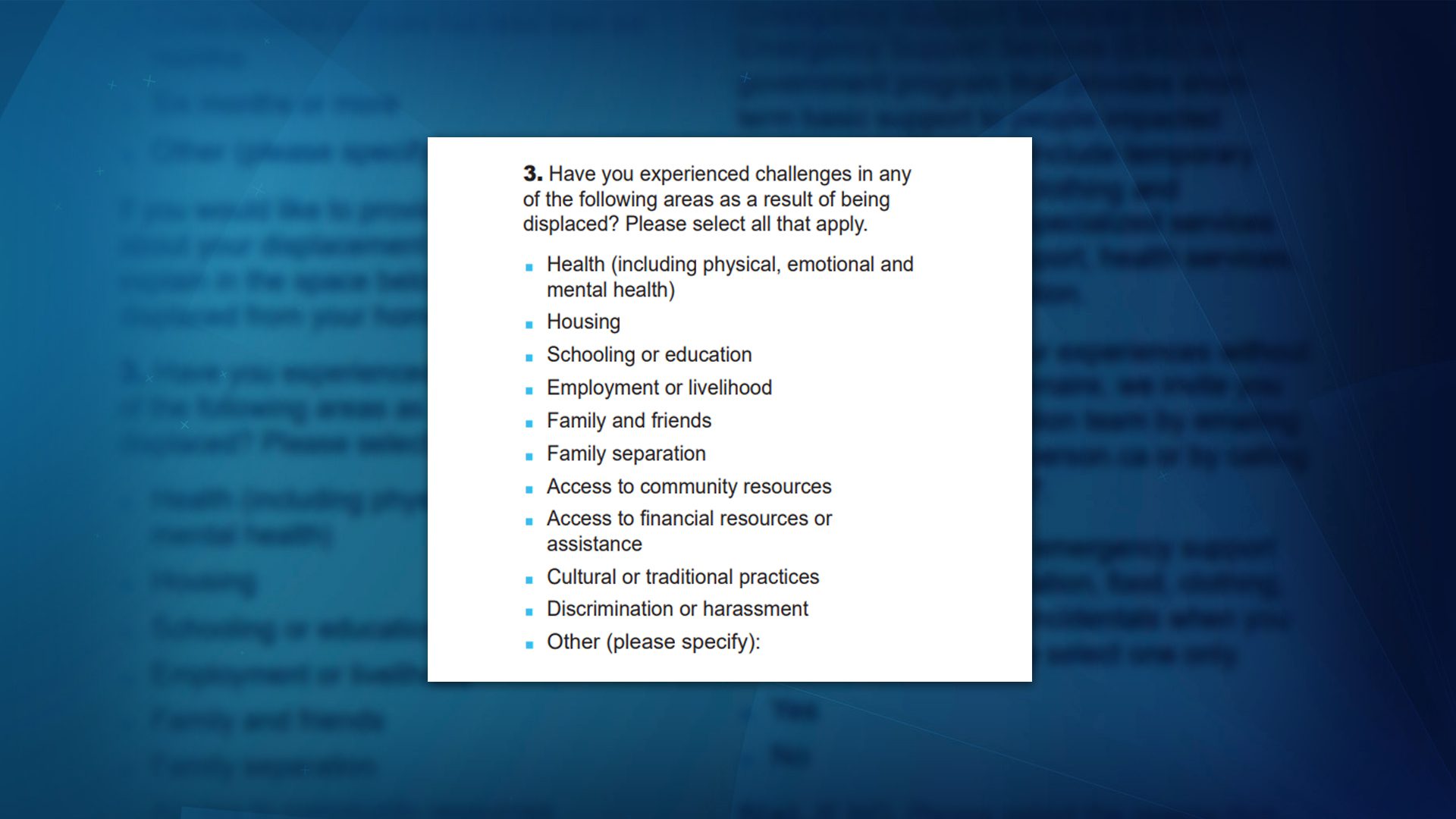

The B.C. Ombudsperson report said that disasters affect different groups of people in different ways.

“Extreme weather disasters are not felt equally by all; instead, they disproportionately impact people who are already socially disadvantaged by colonialism, systemic inequity and structural discrimination,” said the report.

The Ombudsman office spoke with Indigenous groups for the report including Chief Maureen Chapman, Sq’ewá:lxw First Nation, the Minister’s Advisory Council on Indigenous Women, and leadership or personnel from Skeetchestn Indian Band, Shackan Indian Band and Upper Nicola Band, and from Métis Nation British Columbia.

“The province should work together with Indigenous governing bodies to advance Indigenous self-determination in emergency management and report on specific actions it has taken,” reads the report.

A state of emergency stayed in effect in Lytton for almost two years due to the extent of the damage in the community. This prevented many residents from beginning rebuilding. The Insurance Bureau of Canada last year estimated insured losses of the destruction in Lytton at $102 million.

According to local news reports some seniors from the region were still displaced after a year and a half.

The funding provided to displaced people did not consider a situation where people would be out of their homes for so long. The Ombudsman report recommended that the “Ministry of Emergency Management and Climate Readiness develop plans and a policy framework to meet the needs of people experiencing long-term displacement.”

Government releases new emergency management legislation

Also released Tuesday, B.C. said the “most comprehensive and progressive emergency management framework in Canada,” will be introduced.

Emergency Management Minister Bowinn Ma said it will deliver a modernized emergency management approach that is aligned with international best practices to ensure communities are “safer and more resilient”.

Ma said the legislation looks to update what constitutes an emergency to reflect the changing risks posed by climate change while it provides improved tools for response and recovery.

As a part of the new legislation the government announced a taskforce with several First Nations and Métis members including Rosanne Casimir from Tk’emlúps te Secwepemc.

Chalke had not had time to completely review the new legislation but noted that there were several positive announcements such as the inclusion of Indigenous task force members and a recognition of the need to update the current program. He also said that there were still changes to be made.

“Our report is what happens on the ground… some of the programs we were most interested in are really embodied in a regulation,” said Chalke.