Pairs of child-sized moccasins were placed on stage to symbolize the children who died at residential schools. Photo: Mark Blackburn/APTN News

If you are feeling triggered by the events today, the Indian Residential Schools Crisis Line (1-800-721-0066) is available 24 hours a day for survivors experiencing pain or distress about their residential school experiences.

Canadians were urged Saturday to support survivors and not allow deniers to hijack the residential schools narrative.

To do less, is to undermine reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples, said Stephanie Scott, executive director of the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation (NCTR).

“We must respect all survivors, amplify their voice and call out the deniers,” Scott told the third annual National Day for Truth and Reconciliation ceremony in Ottawa.

“We must challenge the people who don’t want to face the truth.”

Scott was one of a dozen officials, dignitaries and survivors to speak during the 90-minute program on Parliament Hill broadcast nationally by APTN News.

While it’s a paid day off for federal government employees, ‘Orange Shirt Day’ is not yet recognized as an official holiday by all 11 provinces and territories.

But Sept. 30 is the time to wear an orange t-shirt and acknowledge the trauma created by the residential school system and the deaths of thousands of children at those schools, said ceremony co-host Charles Bender.

“The legacy of residential schools, day schools, the ‘60s Scoop and the child welfare system have had a devastating impact on Indigenous people and our society as large,” he said.

“In the name of education, Indigenous children were systematically removed from their homes and families, forbidden to speak their languages and, in some cases, were never seen again.”

The NCTR and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) have so far documented 4,140 deaths of First Nations, Inuit and Métis children in the National Student Memorial Register.

The TRC estimated that 6,000 or more Indigenous children may have died due to abuse and neglect in residential schools.

“I am the daughter of a (residential school) survivor and I am also a ‘60s Scoop survivor,” Scott told the crowd of about 1,500 that included Gov.-Gen. Mary Simon and Crown-Indigenous Relations Minister Gary Anandasangaree.

She said without survivors, Canada would not have issued a national apology, established the TRC, or created the NCTR.

“(They) insisted the truth of residential schools must never be forgotten,” she said.

A special day to honour survivors and remember those who didn’t survive was one of 94 recommendations made by the TRC as a way to reconcile the harms of the residential school system.

Kimberly Murray, Special Interlocutor on Missing Children and Burial Sites associated with Residential Schools, urged the federal and provincial governments to do more to recognize the basic facts of the residential school system.

“During the truth and reconciliation process, many of the provinces and territories started to implement curriculum on Indian residential schools and then we see changes in government,” she said in an interview with APTN earlier in the week.

“And then we saw the curriculum being pulled back, and now we see a rise in denialism.”

Ground-penetrating radar searches to locate graves of the children who died in the schools, which were established and funded by the federal government and operated by churches for more than a century, continue across the country.

“The residential school system was intended to destroy First Nations, Métis and Inuit culture and our languages but they did not succeed,” said Scott, as the audience applauded and cheered.

“For those that never made it home, their spirits call out to us to be remembered and to be honoured.”

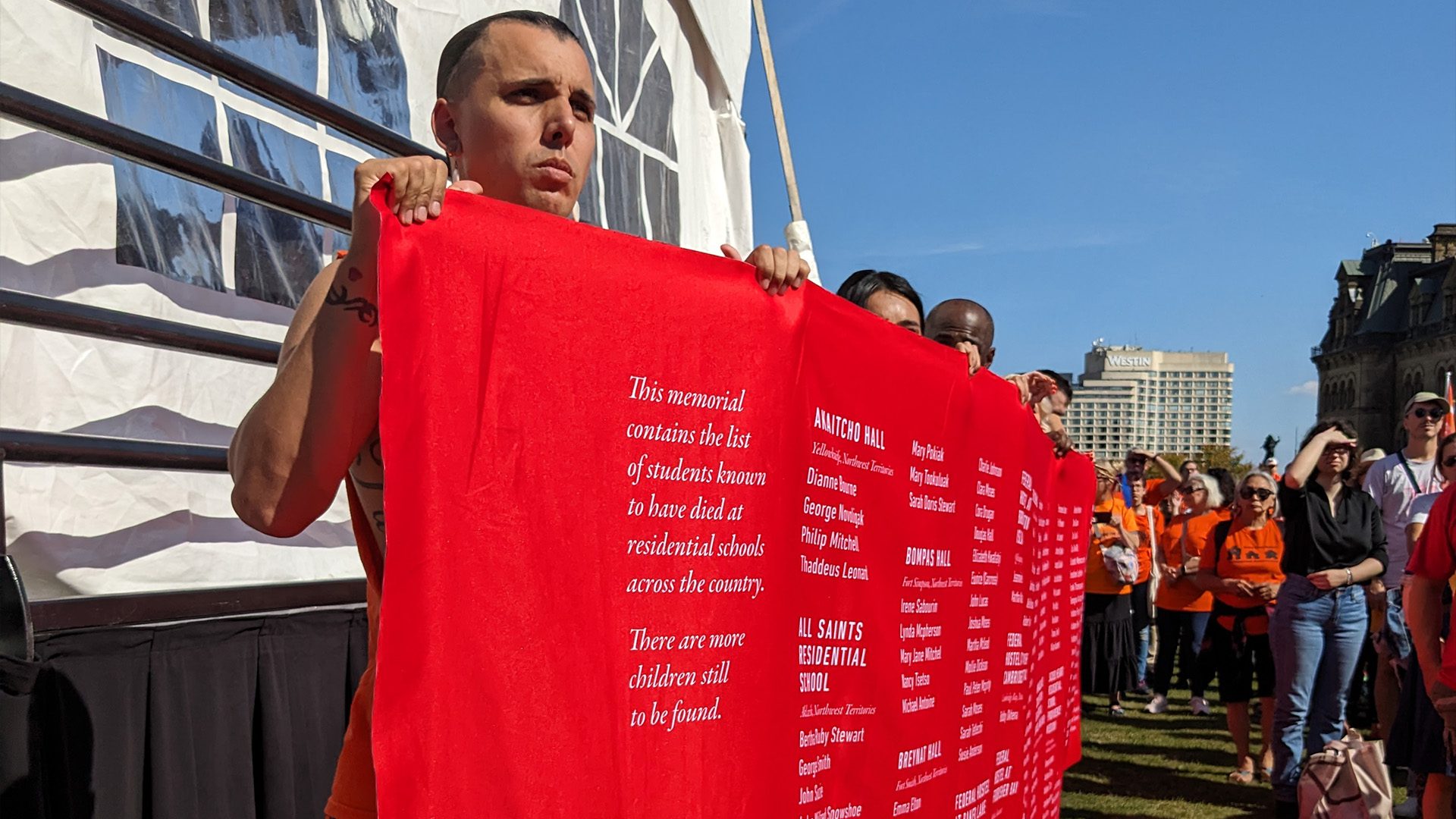

In a powerful show of remembrance, pairs of small shoes and moccasins were placed on stage as special guests carried a memorial banner onto the stage. Members of the audience, adorned in orange t-shirts, stood quietly at attention in the afternoon sun.

Research into the deaths of children at the schools continues, said Scott, as does the NCTR’s efforts to obtain 23 million records not released to the TRC by government and church entities.

“We know more children will be found and their names will be added,” she said.

Jimmy Awa, of Pond Inlet, Nunavut, said the ceremony made him feel better.

He has called Ottawa home since April when he escorted his mother down south for medical treatment. After she died, he decided to stay.

“It’s hard to get a house there,” he said of his home community, “and everything is expensive. So I’m going to try it down here.”

Awa said his mother was sent to residential school, but he didn’t know which one. They never talked about it.

“Finally seems to have relief from a bit of pain that has been going on,” he said, while sitting with a friend on a sidewalk bench a block south of Parliament Hill.

“The stories they told about how they survived. It was really moving.”

The ceremony

Yet. the ceremony, media coverage and orange clothing aren’t for everyone.

Betsy Bruyere of Sagkeeng First Nation in Manitoba admits this long weekend is a struggle.

“Something that really inflames me is the commercialization of our experiences,” she said in a telephone interview. “You see the ads – there’s shirts, there’s hats, there’s all kinds of stuff.”

Bruyere is the fourth generation of her family to be sent to residential school, so she understands the need to create awareness and raise funds for counselling and other services.

But seeing people dressed the same brings up negative feelings for her.

“I find everyone wearing the same thing reminds me of residential school (uniforms),” she said. “I’ve been given two orange shirts and I’ve given them away.”

A look at National Day for Truth and Reconciliation in Ottawa from Annette Francis:

Day off

Bruyere is also bothered that the federal government, which designed and implemented the residential school system, gives its employees a work day off with pay.

“They’re getting a long weekend, overtime pay – over our suffering – and we’re getting nothing. What’s up with that?” she asked.

Still, Ron Ignace, Canada’s first Indigenous Languages Commissioner, appreciated the day.

“I’m a residential school survivor from the Kamloops Indian Residential School and an escapee,” he told APTN of running away from the institution in British Columbia.

“It’s phenomenal to see so many people here and … educate all of Canada,” he said, “because, as the honorable (commissioner of the TRC) Murray Sinclair said, reconciliation is not an Indigenous problem, it’s a Canadian problem.”

With files by Mark Blackburn