A community member speaks at Fort Chipewyan community meeting with Imperial Oil.

Alberta’s energy regulator or AER may have followed all of its own rules, but a new report into the major Kearl Mine spill found they were dated and vague.

As a result, the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation suffered drinking water pollution after the Imperial Oil property leaked over five million litres of wastewater which was discovered in March And the First Nations’ Chief says a lawsuit is on the horizon.

Allan Adam told APTN News the regulator should “lawyer up and expect a [legal] package by Christmas.”

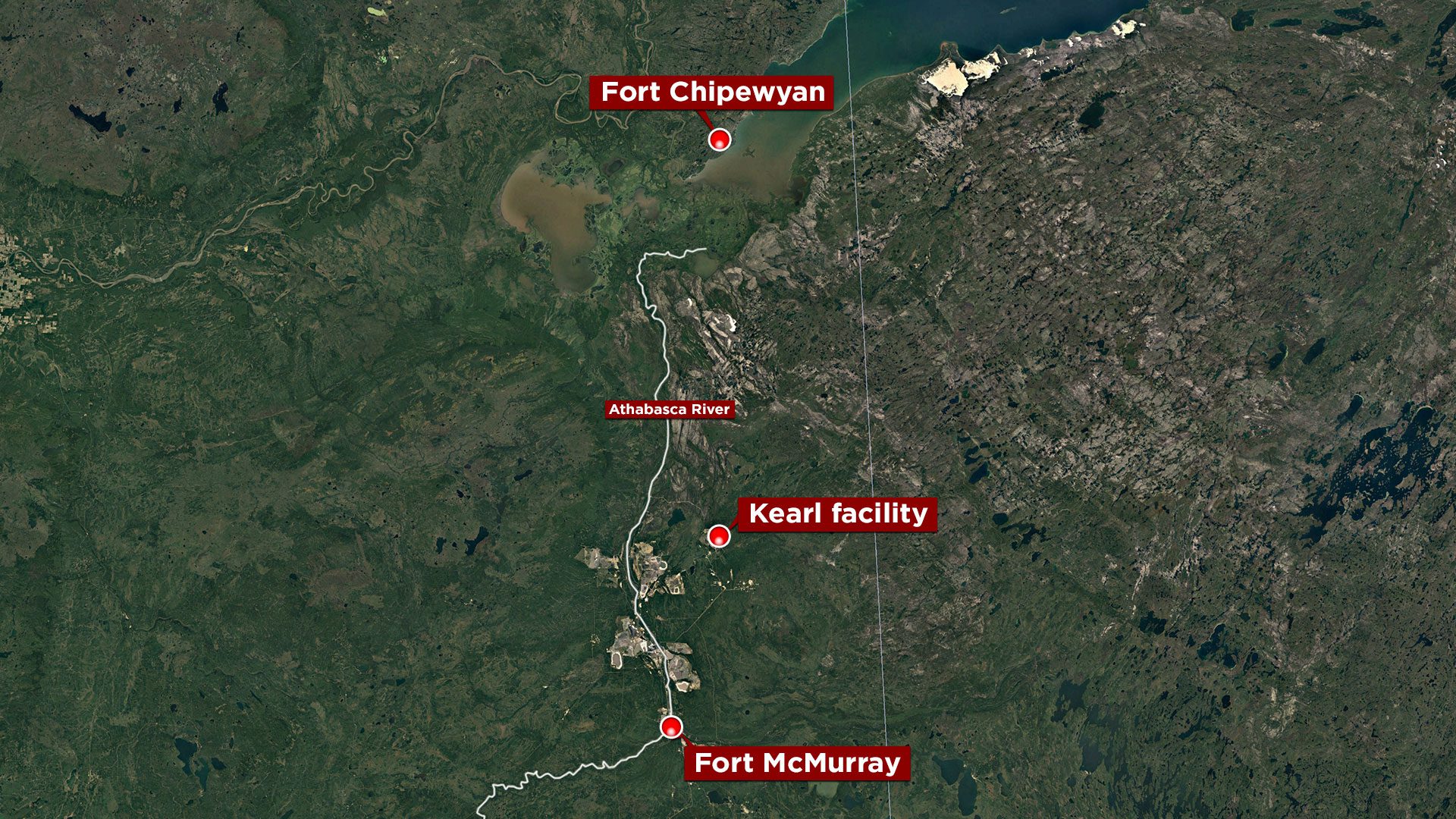

“The Alberta energy regulator as well as the Alberta government failed to protect the communities downstream from Fort Chip,” he said WednesdayThe Kearl mine is about 300 km south .of Fort Chipewyan where many members of the Mikisew Cree Nation, Fort Chipewyan Metis Nation and Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation (ACFN) live.The spill Sat undetected for x time/months, said the report prepared by Deloitte.

Although water quality is being tested regularly, Adam said many in the community have lost trust in the process. He feels a similar spill near a major city, would have been handled differently.

“If it happened in Calgary on the Bow River…they would probably even shut down the mine until they corrected the problem, but in this case the industry kept on pumping tailings water into the area that was leaking,” he said.

The third party, Deloitte, interviewed representatives from 10 Indigenous communities about the actions of the AER.

“All respondents expressed a significant concern with the gap in communications around the event especially in the context of one email to a single point of contact to the communities in May 2022”, said the report.

The communities requested improved communications from the regulator, including an “enhanced notification process” that considered different methods of notification as well as a process to keep contact lists up to date.

The review was commissioned by the regulator’s board after two large releases of wastewater from the mine.

One release was recorded in May 2022 as discoloured water.

First Nations were notified but not given further updates until March, when the release was disclosed as a tailings seepage, along with news of a second release of 5.3 million litres of contaminated wastewater which was an overspill on to nearby land.

Area First Nations were angry and said their members had been harvesting in the area for nine months without being told of possible contamination.

Deloitte found it wasn’t clear if the regulator’s directive on emergency planning for the industry even applies to the oilsands.

They’re all obvious flaws that have been pointed out many times and should have been fixed long ago, said Chief Billy-Joe Tuccaro of the Mikisew Cree First Nation to the Canadian Press.

“We could have written the report for them,” he said. “It’s all stuff that’s simple and should have been fixed long ago.”

Tuccaro said the report lets the regulator off too easy.”Who dropped the ball with the release of information?” he asked. “What are the repercussions?”

Read more:

‘We are probably going to be the first oil sands environmental refugees’

Anger, fear and questions mark a meeting in Fort Chipewyan with Imperial Oil

David Goldie, chairman of the regulator’s board, said the Kearl situation was unusual.

“Most of the incidents the (regulator) deals with are emergencies,” he said. “A pipeline breaks — it’s immediately obvious what’s going on.

“With the Imperial Oil seepage it wasn’t clear what was going on. What it pointed out was the processes and standards and policies were not well designed to handle those kinds of incidents.”

He said the Kearl situation fell into “grey areas.”

Goldie also acknowledged that there was room for improvement according to the report in a press release.

“A key recommendation was for the AER to collaborate with Indigenous communities and key stakeholders to develop specific notification and communication protocols, processes and procedures tailored to meet their needs,” he said in the statement.

The report looks at the regulator’s communications and doesn’t examine Imperial Oil’s actions.

The releases are also the subject of a federal investigation under the Fisheries Act.

With files from the Canadian Press