Michif French had never been written down until five Métis women from Saint Laurent, Man., took on the daunting task of creating the first-ever Michif French dictionary.

The authors – June Bruce, Agathe Chartrand, Lorraine Coutu, Doris Mikolayenko and Patricia Millar – spent five years working on it.

Of the five, Bruce, Chartrand, and Coutu are still living, and are known to many as the “Dictionary Ladies.” Their dictionary earned them an honorary doctorate of letters from the University of Winnipeg.

“The younger ones, they didn’t speak Michif, they only spoke English, that’s why we started this. We wanted everyone to learn,” Coutu told APTN News.

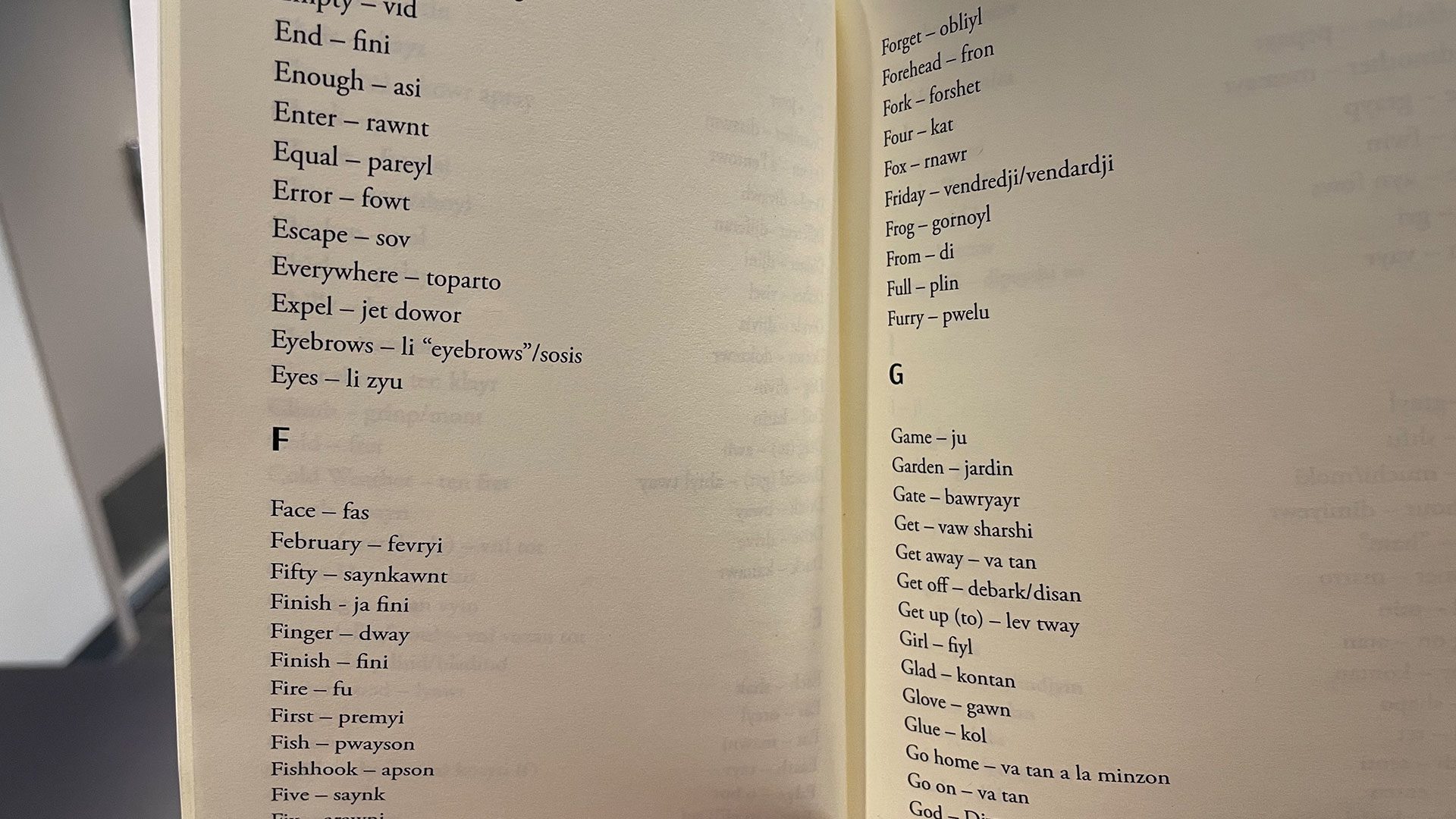

They published Michif French: as spoken by most Michif people of St. Laurent through McNally Robinson Booksellers in 2016.

Métis historically spoke many languages, so michif evolved out of their mixed origins – and their role in the fur trade. Michif is a flexible lanugage that mixes mostly french and cree with its own accent written phonetically.

“All the little surrounding towns, like Saint Ambroise, Saint Laurent, Saint Madelaine, they all have their different ways of speaking, but they all speak Michif French,” said June Bruce

“Skunk, you say ‘moufette’ and we say shikawk,” explained Coutu.

“There are words in there, like I was saying, “on va voir ça” (we will see that), you spell it v-o-i-r, we say “on va wayr,” w-a-y-r, so it’s written differently,” said Bruce.

They were galvanized to start writing the dictionary in 2011 after attending a Michif language conference hosted by the Manitoba Métis Federation.

They realized that the Manitoba Métis federation mostly promoted Michif Cree, and everyone in attendance was speaking a verison of Michif they could not understand.

“All day, we didn’t understand what anyone was saying because they were only speaking Cree. They were laughing, talking amongst each other, and we were sitting there, not understanding a word of what was being said,” said Coutu.

They also wanted to share the language they were forbidden from speaking at school.

“At school, every time you spoke your language, Michif-French, we were yelled at, or they hit our hands, you know, that’s now how you say that, and they said we ‘talked like savages, talking like Indians,’” said Bruce.

“At school, we didn’t understand French, and the sisters didn’t understand us, so it didn’t work,” said Chartrand in Michif French, “The nuns would speak so fast, so we didn’t understand. And we weren’t interested because we didn’t understand. The nuns got discouraged, so they let us do what we want, I guess.”

Chartrand left school in Grade 7. She said many other Michif speakers dropped out of school because it was too difficult to operate in a language they did not understand.

The dictionary is written in English and Michif French so younger people, like Lorraine’s daughter, Andrea Rose, can use it.

“By the time I went to school, because they were taught that Michif French is not like a good French, so I was taught English so that when we go to school we have no problem blending in,” said Rose.

“We lost it is because we had to speak English like to blend in properly I guess. And not be told anything negative or to not go through what they went through, saying it’s not right, or getting the strap, or ruler, or whatever.”

Rose helps Bruce, Chartrand and Coutu lead Michif French classes for kids and adults across Manitoba — while learning along with the students so she can keep the language of her ancestors alive.