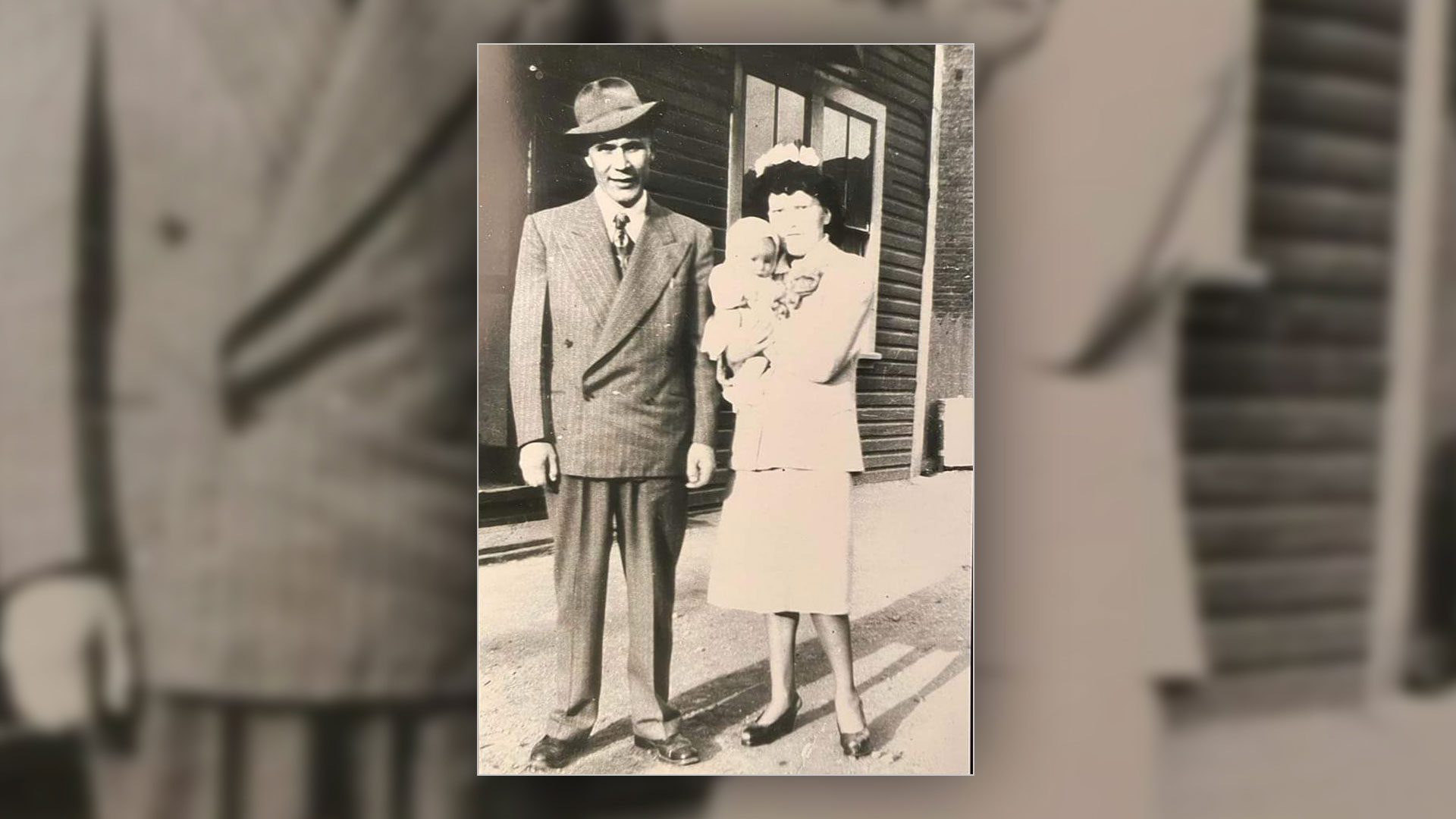

Aaron GreyCloud II holds a black and white photo of his grandparents, Barbara and David Flamming, and declares they are Cree First Nations people from Saskatchewan.

He can see it in their faces. But that’s not what the federal government says.

Three years after his father, Aaron GreyCloud, died in 2016, Aaron II applied for compensation on his behalf from the $875-million Sixties Scoop Settlement agreement.

His father was one of 25,000 to 35,000 First Nations, Inuit, Métis and non-status First Nations children “scooped” from their families and communities between Jan. 1, 1951 and Dec. 31, 1991, and placed with non-Indigenous caregivers. The bulk of the apprehensions occurred in the 1960s.

A group of survivors filed a class-action lawsuit for the loss of cultural identities, and the government settled in 2018 agreeing to pay eligible survivors $25,000 each, and put up $50 million for a ’60s Scoop healing foundation.

“I was looking at the lawsuit they had – the ’60s scoop lawsuit – and I was like, ‘Man, my dad wanted that, but he died before he got that,’ so I was like, ‘I’m going to do that for him’,” Aaron II said.

But Aaron II said the application was rejected because his father was not registered with the government as a First Nations person, also known as being recognized as having status under the Indian Act.

And Métis and non-status First Nations survivors are excluded from the settlement agreement.

The rejection letter gave Aaron II, who lives in Kitimat, B.C., 45 days to provide more information.

“It was so easy for them to write him down as Caucasian and whitewash him,” Aaron II said, “yet it is difficult to undo what they have done.”

Aaron II said he filed a Freedom of Information request for his father’s adoption records in the province of B.C. The records he shared with APTN News show his father listed as “Indian” and “caucasian”.

The son sent the documents to Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) in Ottawa.

The department confirmed it is working on the file, but it’s not looking good.

Based on a search using the records provided, ISC said it was not possible to identify his father as a person who had ever been registered as an Indian.

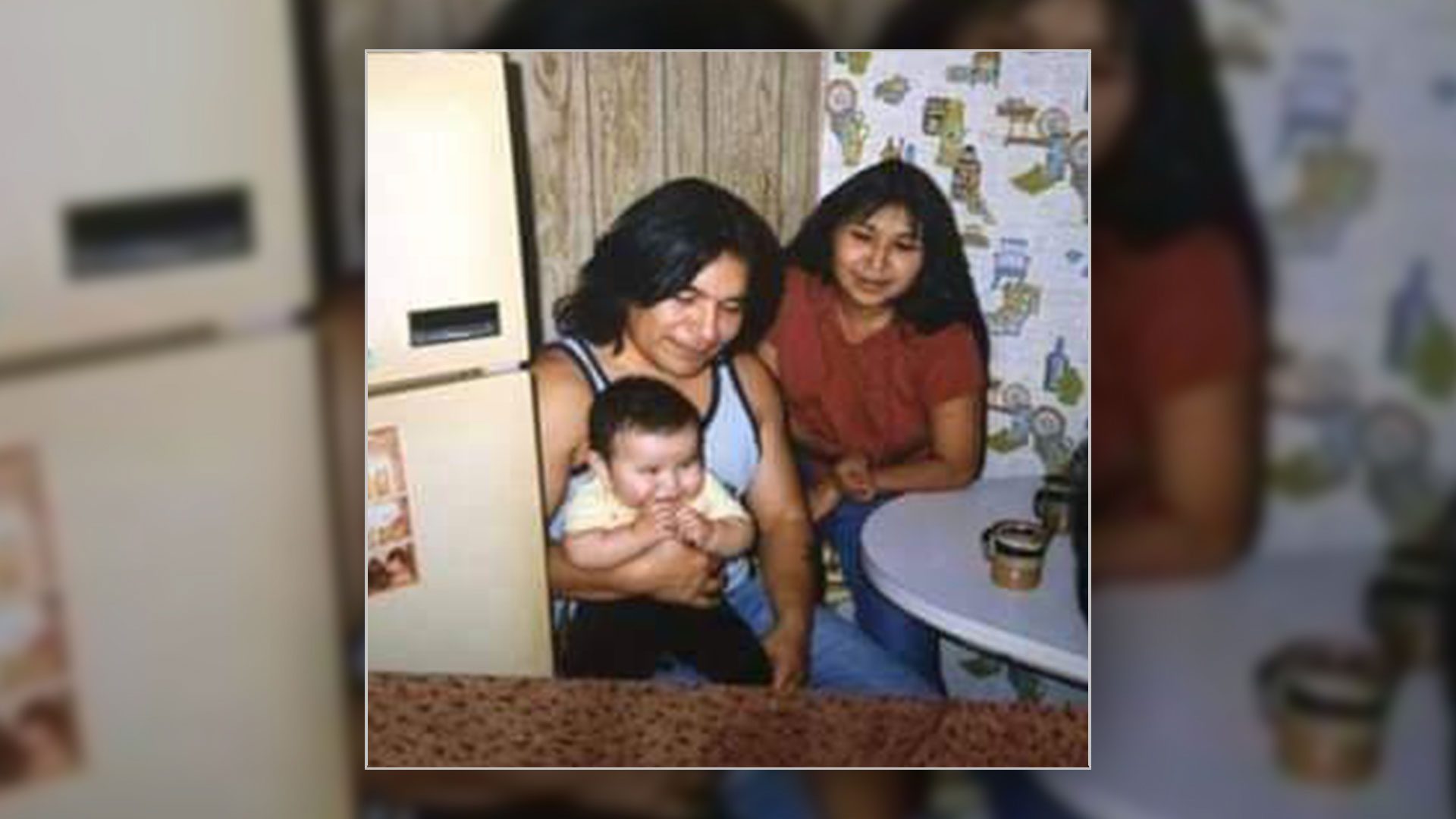

Aaron was placed in foster care in Vancouver in the mid-1950s, his son said.

But it was another policy that eliminated Aaron’s lack of status.

His mother lost her status rights when she married someone without status.

It wasn’t until 2017 when that inequality was corrected in the Indian Act through Bill S-3.

But Barbara Flamming had already died.

Then Bill C31 in 2019 allowed women who had previously lost their status to regain it, as well as their children’s status.

ISC said restored status applies to everyone, including those in foster care in Canada.

“Bill S-3 addresses the known sex-based inequities in the registration provisions of the Indian Act and it applies to individuals in every province, regardless of whether they are in care,” ISC said in a statement.

“Bill S-3 also addressed cases of unknown or unstated paternity, allowing the Registrar to assess all forms of evidence for a child’s ancestry and to make every reasonable inference in favour of the applicant.”

Aaron II said the fight was a significant frustration for his father before he passed away.

He said it will be sad to see his father regain his status without being here to witness it.

“Even if they do accept his application, I regret he is not here to accept it, to be able to revel in it a bit, to be able to feel the victory.”

Aaron II said he is just hoping to get justice for his father and other ’60 Scoop survivors facing similar circumstances.

“He didn’t want revenge; he wanted justice, you know,” the son said. “That echoed through my life.

“At times, I was so frustrated with this process at having my history taken from me. As a young man, I do remember wanting revenge and my dad sitting me down and telling me that’s not the path. ‘You know that’s not going to bring the change we need’.”

Meanwhile, the spokesperson for ISC said the department is working with the settlement claims administrator to improve the process.

“Canada worked closely with the third-party administrator Collectiva to support the administration of the Sixties Scoop Settlement Agreement,” said an emailed statement.

“A key part of this support was to update protocols, processes and systems related to the registration process, with the understanding that these improvements would benefit all individuals seeking registration under the Indian Act, including those impacted by the Sixties Scoop.”

The spokesperson encouraged anyone who thinks they are eligible for status to apply.