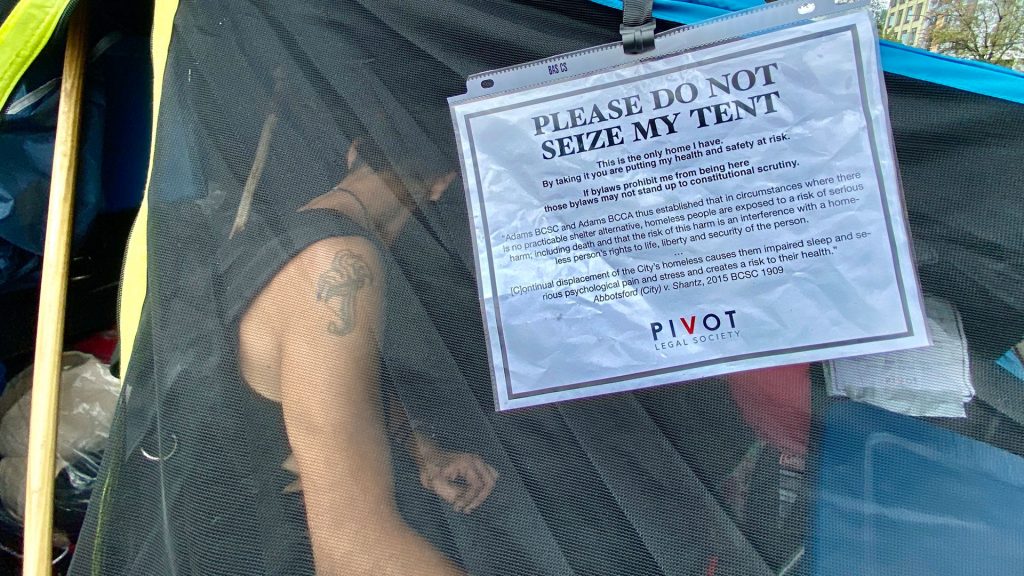

People living on the street in downtown Vancouver don't want to lose their temporary homes. Photo: Simon Charland/APTN News

It was difficult to see any difference had been made to the tent encampment in Vancouver’s troubled Downtown Eastside on Wednesday, a day after city staff began what’s expected to be a weeks-long process to remove the structures.

That’s for good reason, said a resident who goes by the name Edith Elizabeth – the people who live in the tents have nowhere else to go.

She said previously, residents would relocate their structures nearby so city staff could clean the street.

“It’s just like, ‘OK, cool, take down our structures and move down the block so they can wash it,’ and that’s it,” said Elizabeth. “But here, now, it’s just like we have to disappear or something.”

Vancouver fire Chief Karen Fry ordered tents along the stretch of Hastings Street dismantled last month, saying there was an extreme fire and safety risk.

The city has said staff would concentrate their efforts on the “highest risk” areas, but several structures in those areas remained in place on Wednesday.

The neighbourhood struggles with many complex challenges including drug use, crime, homelessness, housing issues, and unemployment.

It can also be a home away from home for off reserve First Nations and other indigenous people.

It was tense on Tuesday, Elizabeth said, with a heavy police presence on the street.

The Vancouver Police Department released a statement Tuesday saying multiple people were arrested after officers were assaulted during a “melee.”

It said staff at a community centre had called police to report a man throwing computers and behaving erratically. The man resisted arrest, police said, as “a large crowd gathered, and became hostile and combative with the officers.”

Elizabeth said police used pepper spray and the incident left people feeling scared.

An update from the city on Wednesday said a big contingent of police at the Main and Hastings intersection in the afternoon “was not as a result of the City’s effort to remove structures”, and instead stemmed from the incident outside the community centre.

The city said staff aimed to approach encampment residents “with respect and sensitivity, encouraging and supporting voluntary removal of tents and belongings through conversation.”

“We recognize that some people believe the city should not do this work, but there are significant safety risks for everyone in the neighbourhood that the city cannot ignore,” it said.

Elizabeth stood near her belongings on the sidewalk where she said she’s been staying for about three weeks after moving from another spot nearby.

“It’s not like this is a forever, permanent place,” she said, although she’s not sure where she might go next.

“As far as options down here, generally there’s been Crab Park, which is like tent city,” she said, referring to tents set up around the park near Vancouver’s waterfront.

Elizabeth said she, like many others living in tents along the street, doesn’t feel comfortable or safe in single-room occupancy buildings with “awful” conditions.

The city said staff have been meeting each week with a community-based working group since May, and more frequently with members of the Overdose Prevention Society and Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users over the past two weeks.

Staff spent Wednesday telling residents about storage options for their belongings, the city said.

These included up to two 360-litre storage totes, which staff would seal with tamper-proof labels before placing them in short-term storage. The city said the totes are on wheels, so owners can take them away if they did not want them stored.

A long-term storage container is also being provided nearby, the city said.

Community advocacy groups, including the drug-user network and Pivot Legal Society, have said clearing the encampment violates a memorandum of understanding between the city, the B.C. government and Vancouver’s park board, because people are being told to move without being offered suitable housing.

The stated aim of the agreement struck last March is to connect unsheltered people to housing and preserve their dignity when dismantling encampments.

The City of Vancouver may enforce bylaws that prohibit structures on sidewalks “when suitable spaces are available for people to move indoors,” it reads.