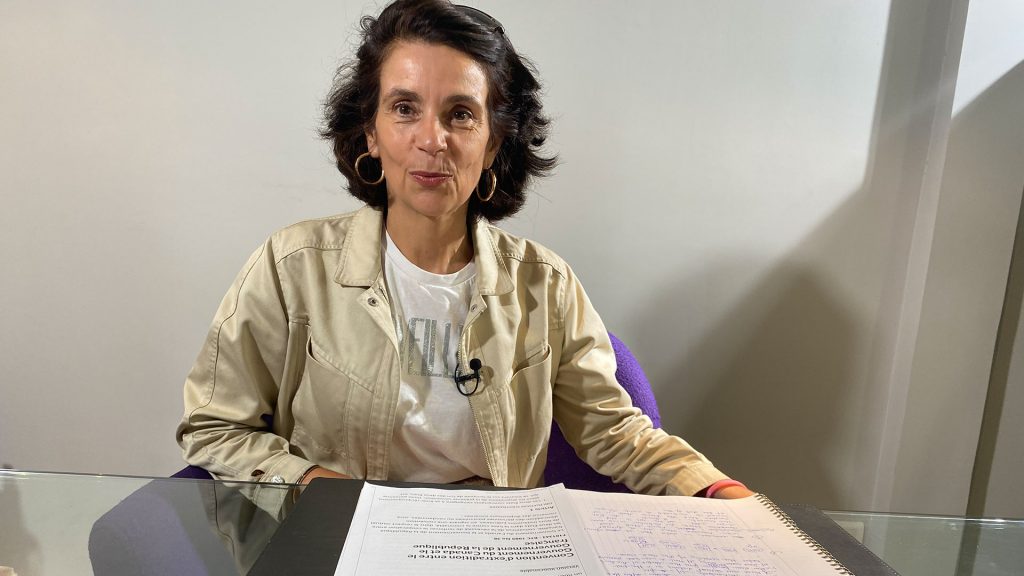

Nadia Debbache is a lawyer in Lyon, France with experience fighting the Catholic church. Photo: Kathleen Martens/APTN

Warning: This story contains details that some people may find disturbing. The Hope for Wellness Help Line offers immediate help to all Indigenous Peoples across Canada. It is available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week at 1-855-242-3310 in English and French and upon request in Cree, Ojibway, and Inuktitut.

It’s probably too late to try a French Catholic priest on a Canadian sex charge in France because the statute of limitations has expired, says a lawyer in Lyon, France.

APTN News asked Nadia Debbache, who has experience suing the Catholic Church in France, to explain French law.

She agreed to speak generally about the case of Oblate Joannes Rivoire because she hasn’t seen the court documents.

A 51-year-old Inuk woman alleges Rivoire molested her for five years while he was serving as a church priest for the Missionary Catholic Oblates of Mary Immaculate (OMI) in Nunavut from 1963 to 1993.

Now 91 and living in an OMI retirement home in Lyon, Rivoire was charged with one count of indecent assault in February 2022. He denied the allegation in an interview with APTN News.

France has two statutes of limitations on sex crimes depending on their severity.

“It’s very complex for France because the law changes all the time,” Debbache said in an interview in her Lyon office.

“Today, the situation for sexual crimes involving children, the statute of limitations is 30 years and begins at the age of majority (or 18).”

That’s for felonies or more serious crimes like rape, she explained.

For misdemeanors – like inappropriate touching – the statute of limitations is 20 years or until the victim is 38 years old.

Debbache said a new law came into effect in 2021 giving alleged victims “a way to benefit from the statute of limitations”, but doesn’t help Rivoire’s accuser at this time.

“If two victims come forward, the first one files a complaint and 10 years later a second victim also comes forward and files a complaint,” the lawyer said. “The statute of limitations begins not when the first victim came forward but when the second victim does.”

Canada has no statute of limitations on sex crimes.

But getting Rivoire to Canada to face his accuser is also unlikely.

That’s because France won’t extradite its citizens to stand trial, a situation that frustrates his alleged victim and her supporters in Nunavut.

That lack of cooperation from France led Canada to abandon five earlier charges of child sexual abuse against Rivoire in 2017 – alleged by four other Inuit – and vacate a Red Notice (Interpol warrant) for his arrest.

So while France is open to prosecuting its citizens at home on foreign charges, Debbache said that option is likely too late.

“That’s why I told you that I don’t know exactly what the situation of the last (alleged) victim was in order to verify if their case is statute-barred according to French law,” she added.

There are still Inuit advocates and politicians calling for Rivoire to be tried in France.

To that end, Debbache suggested the woman file a criminal complaint against Rivoire in France.

Meanwhile, she said victims’ associations – like Ending Clergy Abuse (ECA) – continue to lobby the French government to drop statutes of limitations altogether to give victims more time to report historical sexual abuse and file charges.

Evelyn Korkmaz, a First Nations woman living in Ottawa, helped found ECA and the group Advocates for Clergy Trauma Survivors in Canada. She said ECA is active in 28 countries with thousands of members.

She is a former student of notorious the St. Anne’s Residential School on Fort Albany First Nation in northeastern Ontario.

St. Anne’s was run by two Catholic missionary organizations – OMI and the Grey Sisters of the Cross.

Former students, who prefer to be called adult survivors of child sexual abuse, said they were physically and sexually abused, whipped, beaten, forced to eat their own vomit, and shocked in a homemade electric chair.

Korkmaz, who was 10 years old when she was sexually assaulted, said not prosecuting the abusers sends the wrong message.

“We need these priests, nuns, brothers, bishops and archbishops that did our people wrong to be charged,” she said. “It’s a criminal offence.

“We were children. We didn’t know what sex was at the time. This was our sex education.”

In France, Debbache represented the victims’ group La Parole Libéré in the high-profile case of French Catholic priest Bernard Preynat and his Archbiship Philippe Barbarin in Lyon.

Preynat, at 75, was convicted in 2020 of numerous counts of child sexual abuse and sentenced to five years in prison. Barbarin – in a scandal that reached Pope Francis – resigned amid allegations he shielded Preynat from prosecution.

Debbache said Barbarin’s resignation was a huge victory for the victims’ group that long accused him of covering up Preynat’s abuse.

She said it showed the church hierarchy is not immune to public pressure.

Further, she said the case propelled Catholic bishops to form an independent commission in France to investigate child sexual abuse and sexual violence in the French Catholic Church between 1950 and 2020.

The Commission on Sexual Abuse in the Catholic Church concluded there were between 2,900 and 3,200 pedophiles operating within the church during that period.

Its research suggested there were an estimated 216,000 victims – mostly adolescent boys.

The commission concluded the abuse was systemic.

It said the church did not take necessary measures to prevent and report abuse, and sometimes knowingly put children in the care of predators.

However, the commission did not consider the harms caused by French missionaries, said Debbache.

“In fact, there are many other French missionaries stationed abroad who have committed sexual abuse on victims abroad and have not been prosecuted,” she said in an interview with APTN, “and whom the Catholic Church continues to protect by moving them around.

“This question hasn’t been addressed by the independent commission, and the Catholic church does not want to raise the topic because the number of victims is much, much higher than what we think.”

ECA, in particular, has said the church must reform the “structural mechanism that allows abuse” to end the devastating epidemic of victimization.

APTN, meanwhile, asked Debbache whether France could extradite Rivoire now that he has revealed he is a Canadian citizen.

Debbache said she is not an expert in extradition law and referred the question to French prosecutors.

When pressed, she said she didn’t feel Rivoire’s dual French-Canadian nationality would make him eligible for extradition.

The top prosecutor in Lyon could not immediately be reached for comment.

Part 1: French priest denies sex charge in Canada