In one home, a decayed ceiling crashed to the floor.

In another, 2x4s were erected around a toddler’s crib to prevent escape.

Electric outlets coming loose from the wall. Foul-smelling bed sheets. Water-damaged walls. Mouse droppings in kitchen drawers. A rusted bathtub and rotten wooden stairs.

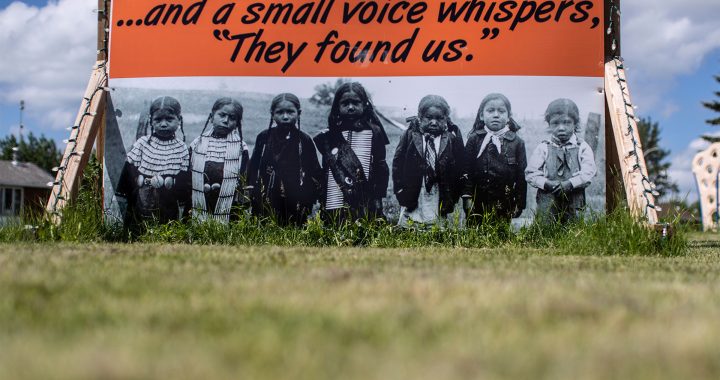

These are snapshots of life inside Connor Homes, according to images provided by former workers and Ontario inspection reports. For more than 45 years, the company has been a major player in the world of private foster care and group homes.

But interviews with more than two dozen former workers, child welfare experts, ministry documents, and court filings tell the story of a private company that some former employees say placed profits over the care of vulnerable children. Experts in the field of group and foster care homes also cite the company’s troubled history, which included a fire at one of its residences in 2017 that killed two people.

A Global News and APTN investigation discovered the key players behind Connor Homes, Bob Connor and his son Sean, have amassed real-estate assets under their own names and through their companies estimated to be in excess of $10 million.

The investigation found the company has also been accused of underreporting serious incidents in its homes, received poor inspection results, and recently surrendered its foster care licence. Connor Homes previously had its licence consistently renewed for its first 40 years of operation.

It’s also a cautionary tale about how Ontario’s child welfare system allowed a private operator with a history of regulatory problems to continue to operate. Global News and APTN are not identifying the locations of the group homes over privacy concerns for the kids in care.

There are roughly 100 private operators in the province.

“These [Connor] homes that I saw were in horrible shape,” said a former worker who Global News is not identifying because of the worker’s fear of reprisal.

“The roofs were disgusting. Electricity not working, water not working properly, the air and heat not working properly.

“That happened on a regular basis.”

In Ontario, children’s aid societies are responsible for investigating reports of abuse or neglect of children and, when necessary, taking steps to protect them. They also may take responsibility for children who prove too challenging for their parents.

If a bed can’t be found for a child within its own network of foster homes, a children’s aid society can turn to a private company like Connor Homes. These companies are part of a $1.8-billion ecosystem providing child protective services in the province, according to the latest provincial data.

In some cases, former staff alleged that Connor Homes would keep kids as long as possible because of the “price tag” attached to them. The province funds children’s aid societies, which in turn pay any private operators they place children with.

Fewer children can mean less revenue.

Interviews with former workers and documents obtained by Global News and APTN raise allegations of hardships throughout Connor’s group homes: limited food budgets, little money for recreational activities or Christmas presents, crumbling infrastructure and low wages for staff.

The Connors also own another business. And it looks very different.

The investigation uncovered a collection of upscale rental vacation properties owned by the Connor family – primarily Bob Connor and his wife – through a separate entity called Windswept.

The company operates three bed-and-breakfasts and rents out four country cottages near Campbellford, Ont. — about a two-hour drive east of Toronto.

Images on its website show pristine lots and cabins overlooking the Trent River. Some rentals include sweeping waterfront views, boat docks, king-size beds and hot tubs. One bed-and-breakfast advertises a themed room with “exotic African” decor and ensuite showers with towel warmers.

Another is housed on a private island that vacationers can fly their floatplane to.

Using property and corporate records, Global News was able to identify at least 18 properties owned by Bob or Sean Connor or through the numbered company 511825 Ontario Inc., which lists Bob Connor and his wife as directors. The properties include group and foster homes, as well as vacation rentals.

A Global News and APTN analysis using market value estimates and property tax assessments from Ontario’s Municipal Property Assessment Corp. show those properties have an estimated value of more than $10.5 million.

When reached by reporters at a home in eastern Ontario, Bob Connor declined to come to the door. His son Sean also declined interview requests and would not answer specific questions related to allegations inside the home, citing “confidentiality” concerns.

The children in the company’s care are “supported with a treatment plan, weekly check-ins, and wrap-around supports from a multidisciplinary team including a social worker, psychotherapist, psychologist, and therapist,” he said in a subsequent statement to Global News.

“Our assessment process was created by Connor Homes and received approval from the Ministry,” he said. “Connor Homes’ operations ultimately strive to exceed the legislated minimum regulatory standards.”

Life inside Connor Homes

Connor Homes operated both a foster care agency that oversaw foster parents and several group homes around eastern Ontario, where kids live in a communal setting with shift workers.

At one time Connor Homes had more than 130 beds across the province in roughly 40 group and foster homes, but now operates just three residences with space for up to 20 kids.

Kids in the care of Connor Homes were often treated as a source of revenue, according to workers who spoke with Global News and APTN.

Former employees say kids lived in residences with damaged roofs, rotten floorboards, and broken windows that the company was slow to fix — even in winter.

“I thought it was disgusting,” said one former worker, who agreed to speak anonymously for fear of retaliation. “They have this beautiful business on one side and then [no] money on the other side.”

“[Kids] felt like they were just there to pay people’s paychecks.”

For every child placed in its group homes, Connor Homes is paid a publicly funded per-diem between $193 and $213, according to internal documents obtained by Global News/APTN. One kid could equal more than $77,000 a year. Kids with more complex mental health needs draw higher daily fees.

A contract for Connor Homes’ foster care agency, obtained by Global News/APTN, showed an area supervisor was paid $10 a day for every child placed in a home they supervised. They could also get a commission of $10 a day for every child placed “in a home that the supervisor opened,” even if they weren’t responsible for supervising it — an incentive to recruit more foster parents.

Experts say private companies like Connor Homes can negotiate higher per-diem rates directly with the children’s aid society or Indigenous wellbeing society.

“Before you know it, it’s $500, $700, sometimes — I’m not exaggerating — $1,200 a bed a day,” said Kiaras Gharabaghi, dean of Toronto Metropolitan University’s faculty of community services.

“It’s quite something that we accept this,” Gharabaghi said.

“The money that exchanges hands is huge. There are some people getting very, very rich.”

Insiders with knowledge of Connor Homes’ operations say they were also concerned that the money wasn’t always reaching the children.

Cutting corners on home repairs, limited funds for outings, and kids going to school with supplies in “grocery bags” instead of backpacks were among the allegations made by workers or contained in company documents reviewed by Global News.

Employees described feeling disgusted with how they were taken for training at “fancy” properties used by the Connors’ vacation rental company, yet kids were living in homes that were falling apart.

“Management was awful. They just cared about the money and not the kids,” said the former employee.

Preparing for inspections

Despite the sensitive nature of caring for vulnerable children, there is little oversight of group homes by Ontario’s Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services.

The ministry has the ability to conduct unannounced inspections at licensed group homes and foster care agencies — and it says it did 100 such inspections in 2020-2021. There are 303 group homes and 121 foster care agencies across Ontario with an unknown number of foster homes, according to data obtained through a freedom of information request.

But former Connor workers said managers often knew about upcoming ministry visits and staff were coached on how to respond to inspectors’ questions prior to their arrival.

“We were thoroughly prepared by our supervisor,” said a former worker. “I thought it was kind of funny that we were now going to fix all of these things that we had been complaining about for months.

“We’re fixing it because we’re getting an inspection done.”

And yet, inspectors still found four Connor group homes in various states of disrepair and kids living in deplorable conditions.

Inspection reports described youth who, at times, lacked basic medical care, such as access to Tylenol and eye care.

According to an inspection report, one boy said he’d lost his glasses at another foster home before arriving at Connor Homes, and was told he’d need to wait nine months for them to be replaced because he was only allowed to go for an eye exam once a year. The inspector noted that staff appeared unaware he wore glasses.

A report says another girl told an inspector that “her mattress was uncomfortable and [she] had to use several old blankets to pile under her sheets.”

Images shared with Global News and APTN by former workers showed a home with a rotting bedroom ceiling that caved in and a roof covered with a green tarp. Staff at the home said they had complained that the smell of mould at one home was so strong it was giving them headaches.

How it started

Connor Homes got its start in 1976, when Bob and Elaine Connor welcomed their first foster child into their own home in Campbellford, Ont. They obtained a licence to operate a group home shortly thereafter.

Two years later, they opened homes in two other small eastern Ontario towns. Three more homes were added in Sudbury a year after that.

The company also operated a licensed foster care agency with a network of “treatment foster homes” that were meant to serve children with complex mental health and behavioural issues.

By the mid-2000s, Connor Homes had more than 40 homes, according to testimony by Bob Connor before the Tax Court of Canada.

It now appears, according to interviews and court files, that Sean Connor has succeeded his father as the one overseeing the company’s day-to-day operations, with just a handful of homes left in operation.

Tax court filings suggest that in the past, Connor Homes has attempted to short-change staff by labelling workers as independent contractors.

Contractors, unlike employees, do not get benefits and are required to pay their own Employment Insurance and Canada Pension Plan contributions.

Between 2004 and 2013, several workers fought to be designated as employees, according to documents obtained from the Tax Court of Canada.

Connor Homes battled vigorously in court against their efforts and was successful in one case.

However, a federal judge ruled in favour of at least three different workers in 2013 and combined eight other appeals related to other workers into one judgement.

Low serious occurrence reports

The revelations about the conditions inside these private group homes are part of an ongoing Global News/APTN investigation that has found the child welfare system mistreats some children, lacks qualified staff, and has little oversight or accountability.

The investigation obtained data on over 10,000 serious occurrence reports (SORs), which are required by the province when a child dies, is injured, goes missing or is physically restrained while in care, among other reasons. Although group homes have far fewer beds overall than foster care agencies, they account for roughly half of all SORs in residential settings.

Despite allegations from former staff and other court or ministry documents outlining troubling conditions in its homes, Connor Homes filed few of these reports.

SOR data obtained through freedom of information indicates Connor Homes submitted just three SORs from June 1, 2020, to May 31, 2021 — two for incidents at foster homes, and only one for an incident at a group home.

But the Global News/APTN investigation uncovered 17 calls to local police from three homes operated by Connor Homes during this period.

Police listed the reason for nine of these calls as “trouble with youth,” an assault, or a missing child. These likely required the filing of an SOR with the ministry, but none was reported.

An audio recording provided to Global News and APTN revealed a manager advising staff on when and how to fill out a serious occurrence report.

The recording — of a staff meeting held in 2020 ahead of a ministry inspection — revealed workers were confused about the SOR reporting process.

“I’ve never reported one, I don’t know, honestly,” said a staff member when asked about the reports.

Ministry inspections at one home on Oct. 21, 2021, found seven instances of incidents which required SORs to be filed but none were submitted. A government tribunal examining Connor Homes’ foster care licence in 2020 also highlighted that Connor Homes failed to file these important reports on two occasions.

2017 fire kills 2 at group home

In 2017, a fire tore through a Connor Homes foster home near Lindsay, Ont., killing 14-year-old Kassy Finbow, and one of the caregivers, Andrea Reid. Another worker was injured in the blaze.

An investigation by the local children’s aid society found a sliding glass door had been sealed off in the room where Finbow and Reid were found and a gable window made of Plexiglas couldn’t be fully opened.

Four years later, inspectors found a window bolted shut with Plexiglas at yet another Connor home, reports showed. The documents suggested the issue with the plastic window was later addressed by the home.

The deaths sparked a multitude of investigations and a flurry of lawsuits. More than $7 million in legal actions were filed against Connor Homes by victims or their families. Some of those cases have since been settled.

In response to a $5-million lawsuit filed by the Reid family, Bob Connor said the “allegations are without merit as this home complied with and exceeded the regulations of fire, health and licencing.”

Connor Homes, for its part, filed a $17.5-million lawsuit against the Kawartha-Haliburton Children’s Aid Society after the CAS began refusing to place kids with the private company.

Two years after the fire, the Ministry of Children’s and Community Services gave notice that it was refusing to renew Connor Homes’ foster-care agency licence. The company appealed that decision to the Ontario Licence Appeal Tribunal.

In 2020, the tribunal ruled against Connor Homes, finding 16 reasons not to renew the licence.

Among the infractions, the tribunal found that the company was operating the property not as a foster home with a full-time, live-in caregiver, but rather as “an unlicensed children’s residence” with staff who worked in shifts.

It also found other potentially dangerous conditions.

At a foster home in 2019, ministry personnel found the crib of a toddler “jury-rigged” with 2×4’s to prevent the child from getting out of bed. The foster parent reported the child was disruptive and would not stay in bed.

The tribunal concluded that the “business end” of Connor Homes’ operations — its efforts to ensure a continuous supply of children and to maximise revenue — was sophisticated.

“It is regrettable that Connor Homes did not bring a similar degree of focus and sophistication to bear on execution — oversight, training of staff and the care provided to children,” the Licence Appeal Tribunal ruling said.

Connor Homes appealed the ruling in divisional court, and in April 2021, had the tribunal’s decision overturned. However, on the eve of a new tribunal hearing, Connor Homes surrendered its foster care licence on May 5, 2022.

Sean Connor said staff and foster parents who worked at Connor Homes’ “underwent regular training and ongoing check-ins from their regional CAS leads.”

Connor Homes said that following the fire, the company engaged two independent experts “to review and evaluate our Residential Care program.”

“It was the opinion of these experts that Connor Homes provides safe, quality care to our children and we have been able to achieve good outcomes for them,” he said. “This incident remains a horrible nightmare for the families involved and for our staff and community.”

The ongoing Global News/APTN investigation, which found allegations of wrongdoing in private homes owned by other operators, highlights the questionable role the private sector has had in Ontario’s child welfare system.

Even the children’s aid societies, while fully funded by the province, also operate independently of the government.

Some experts say privatized care takes the “heart” out of caring for vulnerable kids.

“It’s very much on the periphery,” said Gharabaghi, a leading expert in child welfare. “Many people, many child welfare workers, will tell you they hate group homes. They hate private operators.

“But they have to use them because they don’t know what else to do. Nothing else is being generated through our public systems that is replacing the need for these things.”

Ontario’s Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services said in a statement the ministry is “enhancing oversight and accountability” in the child welfare system.

The province said it has also changed its guidelines to increase the number of youth and staff interviews conducted for foster care licensing inspections.

Connor Homes continues to have children in three of its group homes, which raises the question: if the company was found unfit to operate foster homes, how is it still running group homes?

That’s a question that hasn’t been answered.

“A lot of people don’t know about what happens. And they need to,” said a former worker. “They need to see what’s going on and why.”