A First Nations man from Ontario says after searching for decades, has now found the resting place of his mother.

“As a child, you don’t realize what really happened, sometimes I used to think maybe she found somewhere else to live her life, to carry on,” said Saul Day. “I was hoping that was it.

“So, there was nobody at all to give me any information so all these years we’ve been searching, so today I found closure.”

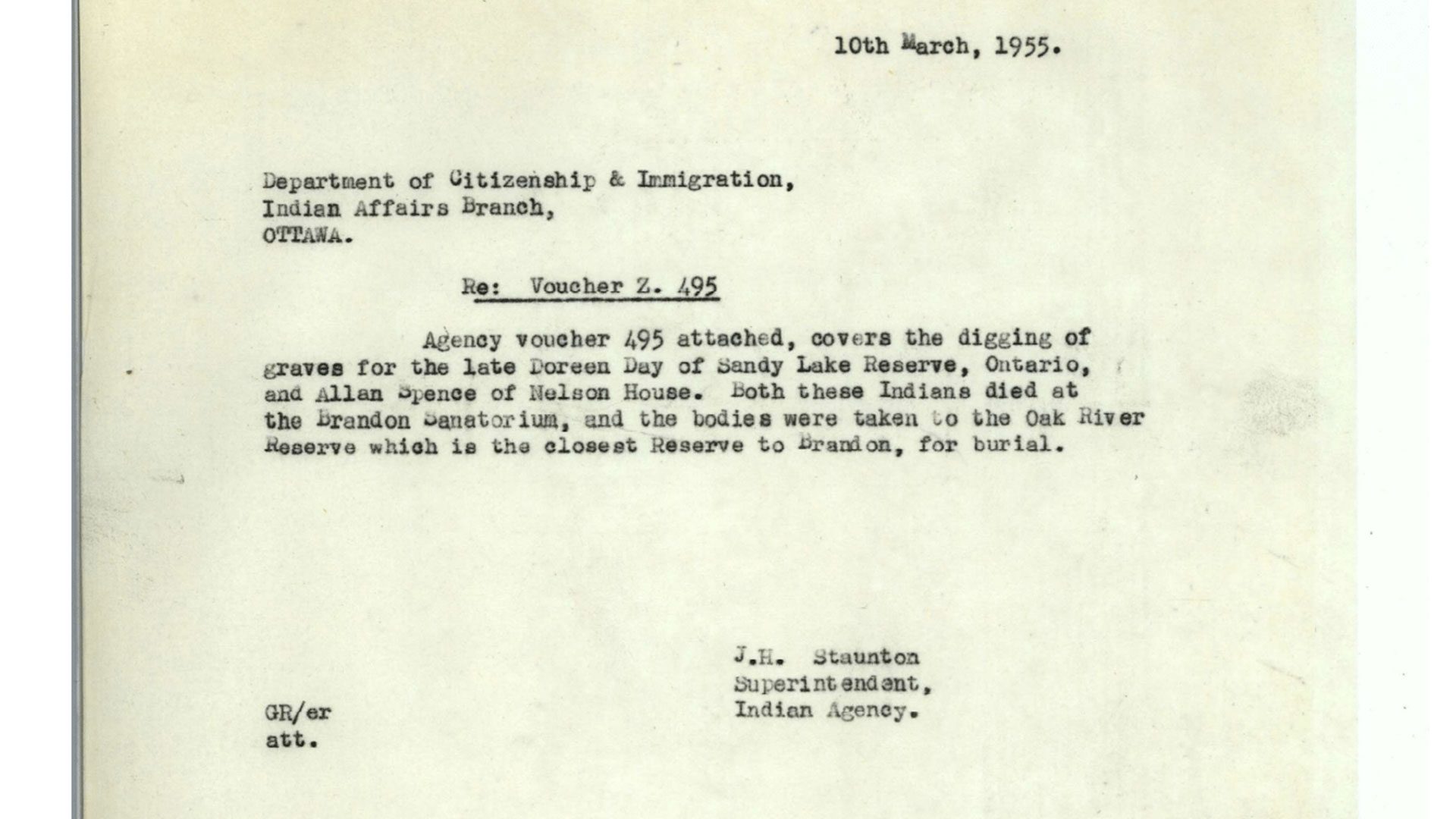

Day has been searching for his mother Doreen Day for more than 50 years and now, thanks to the Manitoba Indigenous Tuberculosis History Project (MITHP), he’s found her final resting place in a cemetery in Sioux Valley Dakota Nation.

The project was set up to help find those missing Indigenous patients from Manitoba sanitoriums, through archival photos and documents.

His mother was taken as a TB patient in the early 1950s from her home on the Sandy Lake First Nation in northern Ontario and transported to Ninette Sanitorium in Brandon, Man., 30 minutes from Sioux Valley.

He had looked at other residential school sites and churches with no luck.

Day, himself is a residential school survivor and was also a TB patient, was sent to a sanitorium close to his home in Ontario.

He said no child should ever have to live without their mother.

“Living without a mother is so devastating, it’s not good for any young person. I’m 76 years old today. To feel that closure, my inner child is well now,” he told APTN News.

The team at MITHP went through numerous documents and photos when they recognized his mother’s name and started looking int where she was buried.

Erin Millions is the research director with MITHP and said one thing researchers have noticed is the correlation between residential schools, sanitoriums and hospitals.

“The other thing that Mrs. Day’s case points to is the importance of archival research and helping to find missing Indigenous patients and also residential school students. The more and more we get into this research, the more we are finding that the tuberculosis sanitoriums and Indian hospitals are interconnected with residential schools to a far greater extent than any of us thought,” Millions said.

She added a step by step guide will launch on Jun. 21 to help families do the work themselves.

“We’re at about 25-30 families we’ve helped or individuals with burial places that we’ve found. Now this isn’t the focus of our work, actually finding the location is not what our main goal is. Our main goal is to produce a research guide that will help people walk through the steps of doing this on their own,” she said.

For Day, he hopes his story can encourage others to keep looking

“It was tragic yes for a lot of us at that time, so now some of us are finding closure. I think it’s important that I share my experience with people.”