Mi’kmaw fisher Fabian Francis is out on the water in the pitch black with a net, skimming the surface of the water.

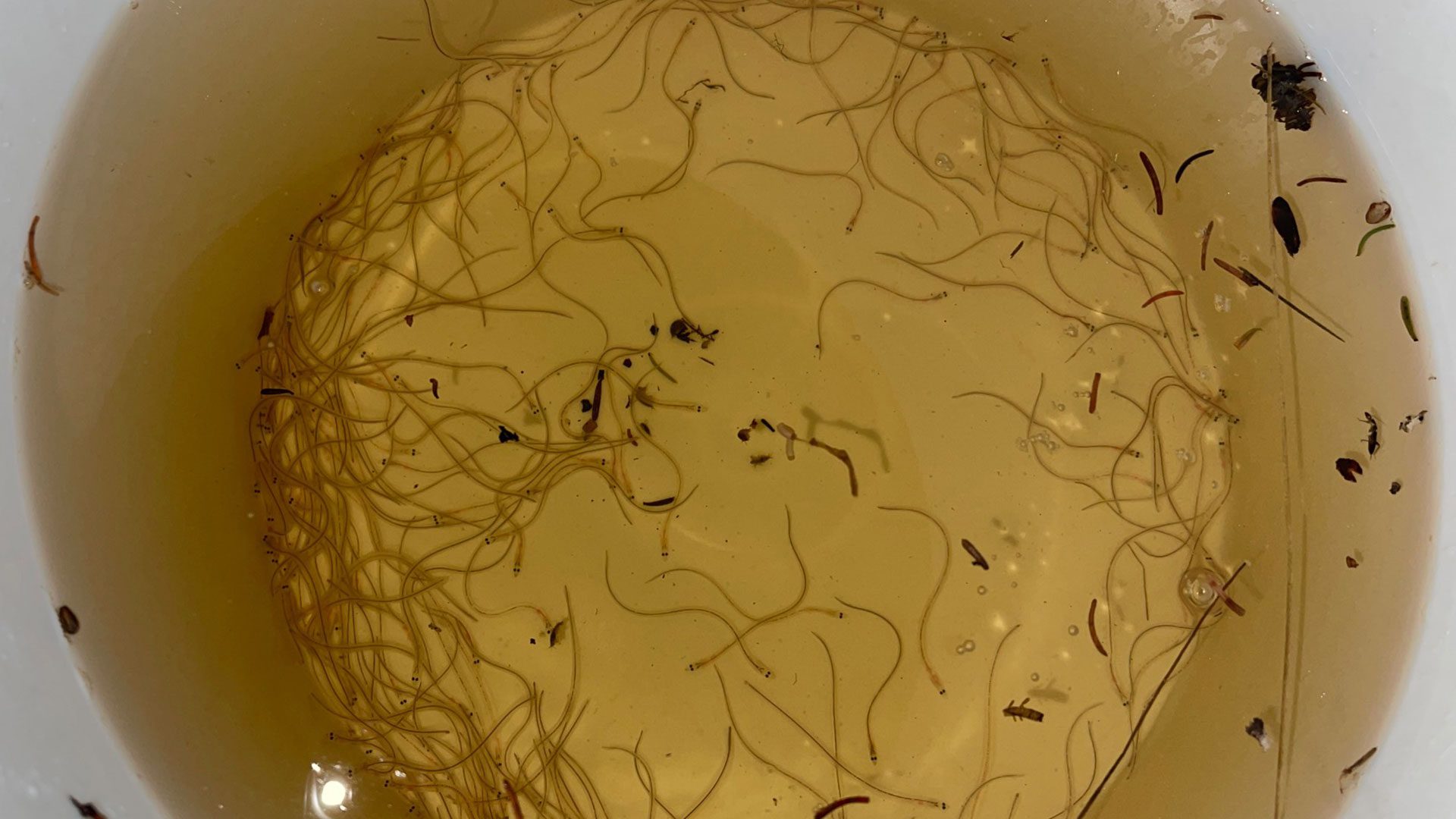

He’s fishing for baby eels – also known as glass eels or elvers.

Francis is out at night because that’s when they come to the surface – and it’s easier to steer clear of officers with the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO).

What Francis is doing is “illegal” in the eyes of the federal government because he is fishing to earn a moderate livelihood.

He’s constantly on the watch for DFO officers.

And finally, he sees them.

“It’s DFO across the road now, so we’ll find out pretty soon, you know DFO, RCMP, everybody’s after us, we can’t even fish for a livelihood,” he says.

Elvers are a lucrative fishery and sell for up to $5,000 a kilogram.

The baby eels are sent to Asia where they’re raised for food.

Some Mi’kmaw communities are harvesting elvers for a moderate livelihood, under their own management plan.

According to the government-approved management plan, there are nine licences in the Elver Fishery, eight commercial licence and one communal commercial licence.

The DFO cut 14 per cent of the commercial fishery quota and is distributing that quota to Mi’kmaw First Nations to develop a moderate livelihood fishery.

Elvers are the latest resource the federal government has recognized as the Mi’kmaw treaty right to earn a moderate livelihood.

In the last few years, Mi’kmaw communities have government-approved moderate livelihood management plans to harvest lobster.

The Mi’kmaw communities implementing their own moderate livelihood fishery management plan to harvest elvers are Annapolis Valley, Acadia, Bear River, and Glooscap First Nations.

The communities have reached an understanding with the Department of Fisheries on how they will take to the waters.

Eric Zcheile, the negotiator for the Assembly of Nova Scotia Mi’kmaw Chiefs, says it’s necessary to monitor the elvers.

“The concern becomes if we don’t know what is taken out, if we don’t have people monitoring the fishing, looking at what the stocks look like coming up, then we are missing, we are just waiting for it to crash, and we don’t want to see that happen,” he says.

Francis is from Eskasoni First Nation – not one of the communities who’ve implemented their own management plan.

Francis says he has a treaty right to fish and the government should not intervene.

“We’ve been here for thousands of years and we fished like this for thousands of years, with no problem,” he says.

He says his community can’t wait.

“A lot of the reserves is poverty, homelessness, suicide, you get addictions and people are doing this because they don’t have any, you know anything to look forward to,” he says.

Francis says he doesn’t believe he’s doing anything illegal. Mi’kmaw has a treaty right to earn a moderate livelihood.

His attention turns to the DFO officers in the distance.

“They are probably taking pictures, whatever they are doing right, you know they’ll come over and talk to us and they’ll say, they’ll see the elvers, and you know they’ll arrest me or whatever they are going to do to us.”

On this night – it’s a wasted harvest.

Fisheries officers pull up along the bank of the river.

“DFO showed up and changed the whole ball game, I had to do what I had to do to protect me and my family, so I had to dump the elvers, reluctantly, I wasn’t too, I didn’t want to dump them but, then again, I can’t fight my rights if I’m in jail.

Francis speaks with the officers saying, “why do I have to go around hiding like a criminal on my own ancestral territory so what are you guys going to charge me or are you going to let me go?”

According to the officer, they’re there to enforce the law.

“We do not want to cause you any trouble,” the officer says. “We just want to let you know, as fisheries officers, we’re here to enforce the fisheries act regulations.”

But Francis says this is just a temporary setback.

While Francis is going home empty-handed on this night, he says it won’t stop him from exercising his treaty right to fish in the future.

“We lost our elver catch, five hours of elvering for nothing, we had to dump it, and I spoke to them and I told them, I told them I was going to go out and do it again,” the Mi’kmaw fisher tells APTN News.

There are a couple of months left in the elver fishery in 2022.