A national study says one in three young people experience dating violence. Photo: APTN file

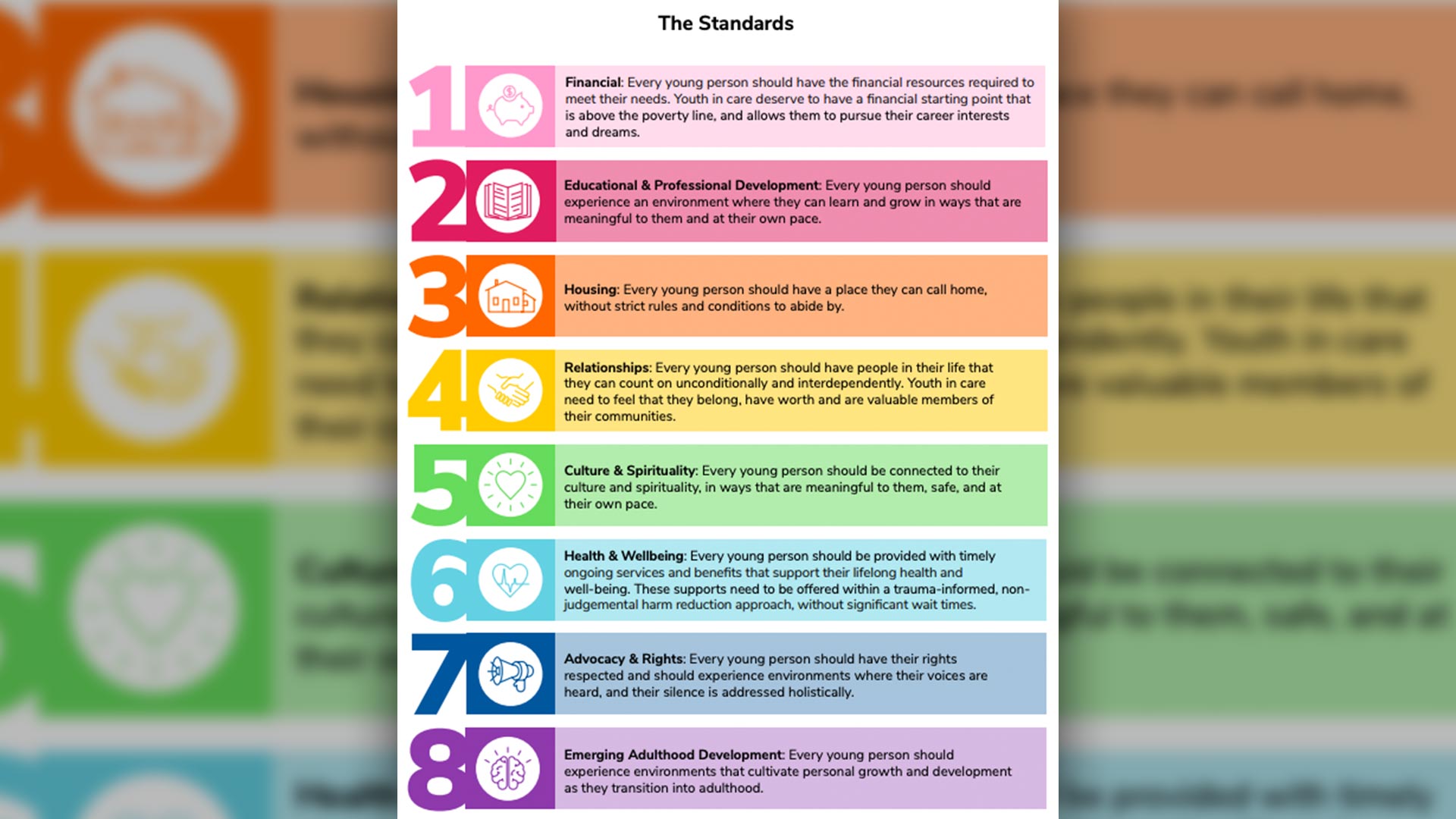

Youth advocates in B.C. have created an eight-step plan called Equitable Standards for Transitions to Adulthood for Youth in Care — and they’re calling on federal, provincial, and territorial governments in Canada to meet them.

“Parents don’t disown their children at the age of majority and push them out the door,” says Melanie Doucet, senior researcher and project manager for the Child Welfare League of Canada (CWLC).

“That’s not how it works in the real world.”

Young people in government care should be able to make that transition to adulthood “with the same level of opportunities and support that their peers get from their families, from their communities and from their friends,” she says.

On Monday, the CWLC released a report outlining eight equitable standards developed in collaboration with the National Council of Youth in Care Advocates.

When youth transition out of government care at 18 or 19 (depending on the jurisdiction) they lose access to many supports, like housing, for example.

And while most areas offer post-majority supports and services, according to the CWLC’s report, eligibility criteria can be restrictive.

“It’s an abrupt precipice that they’re kind of pushed into, without the support that they need to be able to thrive, so they’re constantly in survival mode,” says Doucet. “It’s not legislated or mandated for the ministry to provide services post age of majority. It’s not in the law, so it has to change.”

Standards created by youth, for youth

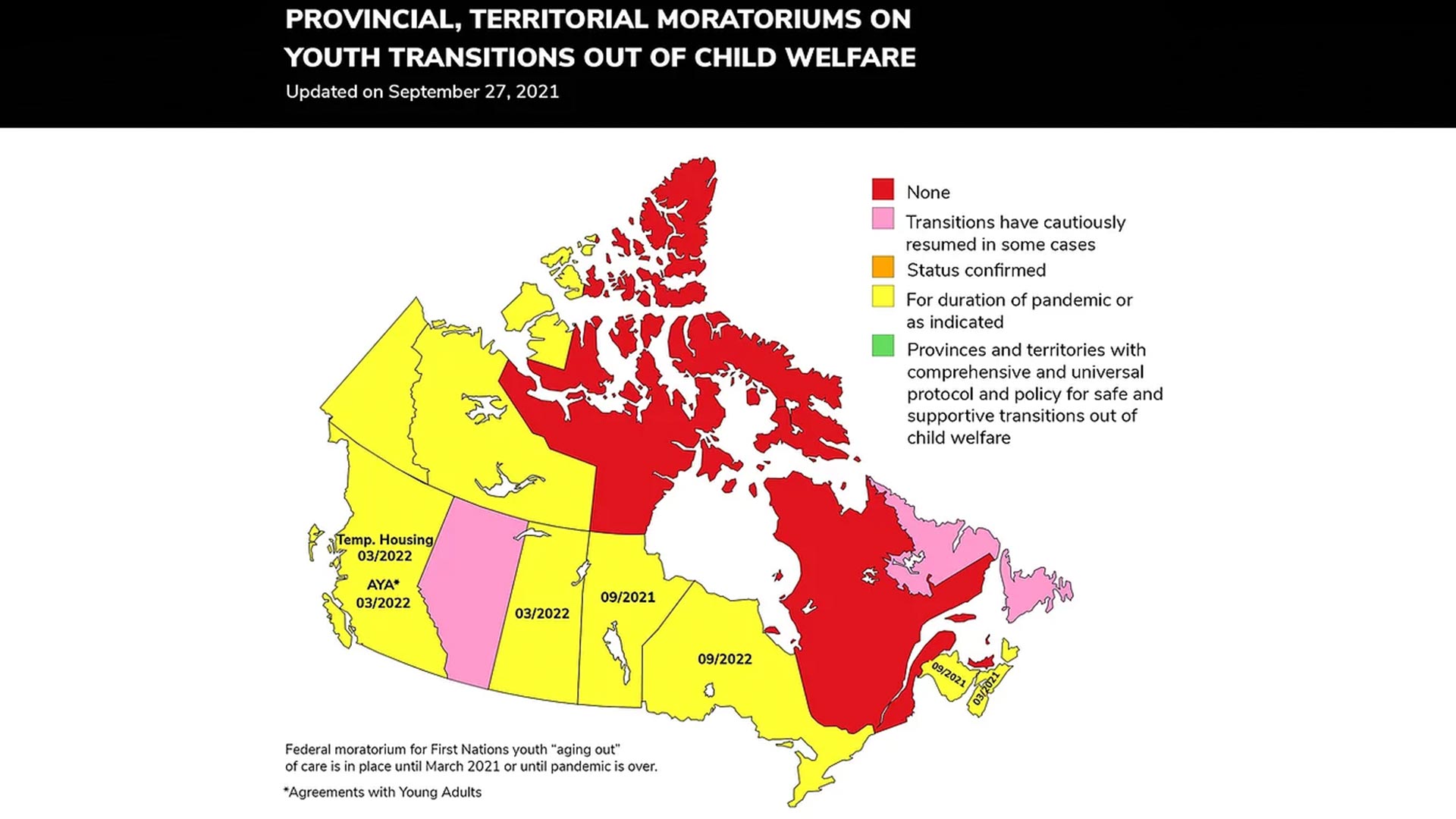

In March 2020, the youth council “called upon provincial, territorial and federal governments to issue moratoriums on aging out of care during the COVID-19 pandemic” — and most jurisdictions followed suit, putting emergency measures in place, says a statement published by the council on Monday.

These measures ensured that youth could remain in care with access to government resources during the pandemic, says Doucet.

“We were really concerned that young people were aging out in these conditions,” Doucet says. “This [pandemic] was just heightening the danger for young people and also exposing them to … health risks as well that weren’t there pre-pandemic.”

Doucet says she transitioned out of care in New Brunswick in the late ‘90s. Today she holds a Ph.D in social work and is passionate about implementing change within the child-welfare system.

The problem with these moratoriums is that they’re temporary, she says. Though most jurisdictions have extended emergency measures until March 2022, they still have expiration dates. We need long-term solutions, she says.

Most laws and policies concerning youth transitions out of government care were developed in the ‘70s or ‘80s, she adds, and they don’t reflect current social and economic realities or scientific knowledge.

“We need to modernize the legislation so that it’s actually meeting youth today where they’re at.”

The equitable standards co-created by CWLC and the youth council “cover eight areas in which youth in care need support to ensure a successful transition to adulthood.”

These areas include financial, educational and professional development, housing, relationships, culture and spirituality, health and wellbeing, advocacy and rights, and emerging adulthood development.

Doucet points out that the standard and solutions put forward in this new report were created by youth with lived experience in the system — people who’ve been through foster homes and group homes. They’re not asking governments for answers, but rather for accountability.

“I guess the next step for our project is that we want … government[s] to evaluate where they’re situated in meeting those standards,” says Doucet.

Over the next year, she says they’ll be developing a fidelity model — “basically like an evaluation process” — based on consultations with governments, trustees, advocates, frontline workers and youth stakeholders.

‘These standards are just the beginning’

Susan Russell-Csanyi is the organizer of Fostering Change, a B.C.-based youth advocacy group.

“Ontario is generally seen as the gold standard for youth transition support … British Columbia is a close second because there are transition supports, but the transition support program that exists — Agreements with Young Adults — doesn’t serve all youth and only serves some,” she says.

“That financial support can also be clawed back,” Russell-Csanyi says. “It feels like a punishment for being in the government care system — because of the hoops that you have to jump through to receive this support.”

She points out that about 900 youth are set to transition out of care in B.C. this year, according to the most recent data from the Ministry of Children and Family Development. And compared to their peers, these youth are at greater risk for outcomes like homelessness.

In 2016, a national survey of more than 1,100 youth who had experienced homelessness, found that nearly half — 47 per cent — “had a history of placements in foster care and/or group homes.”

Researchers concluded that “inadequate income and supports” play a role in creating “difficult transitions” for youth coming out of care.

And these “poor transitions are also correlated with higher rates of unemployment, lack of educational engagement and achievement, involvement in corrections, lack of skills, and poverty.”

Russell-Csanyi says Fostering Change will be holding all governments accountable to ensure the national equitable standards developed by her peers are met.

And these standards are just the beginning, she adds.

She and Doucet would both like to see age-based support cut-offs done away with when it comes to youth who have been through government care.

“This age cut-off has to completely disappear from the equation, and it has to be based on their sense of readiness,” says Doucet. “That’s really the dream … and that’s really what we’re ultimately striving for.