Warning: This story contains details about Indian Day Schools that may be upsetting. The Hope for Wellness Hotline can be reached 24 hours a day at 1-855-242-3310 or online at www.hopeforwellness.ca

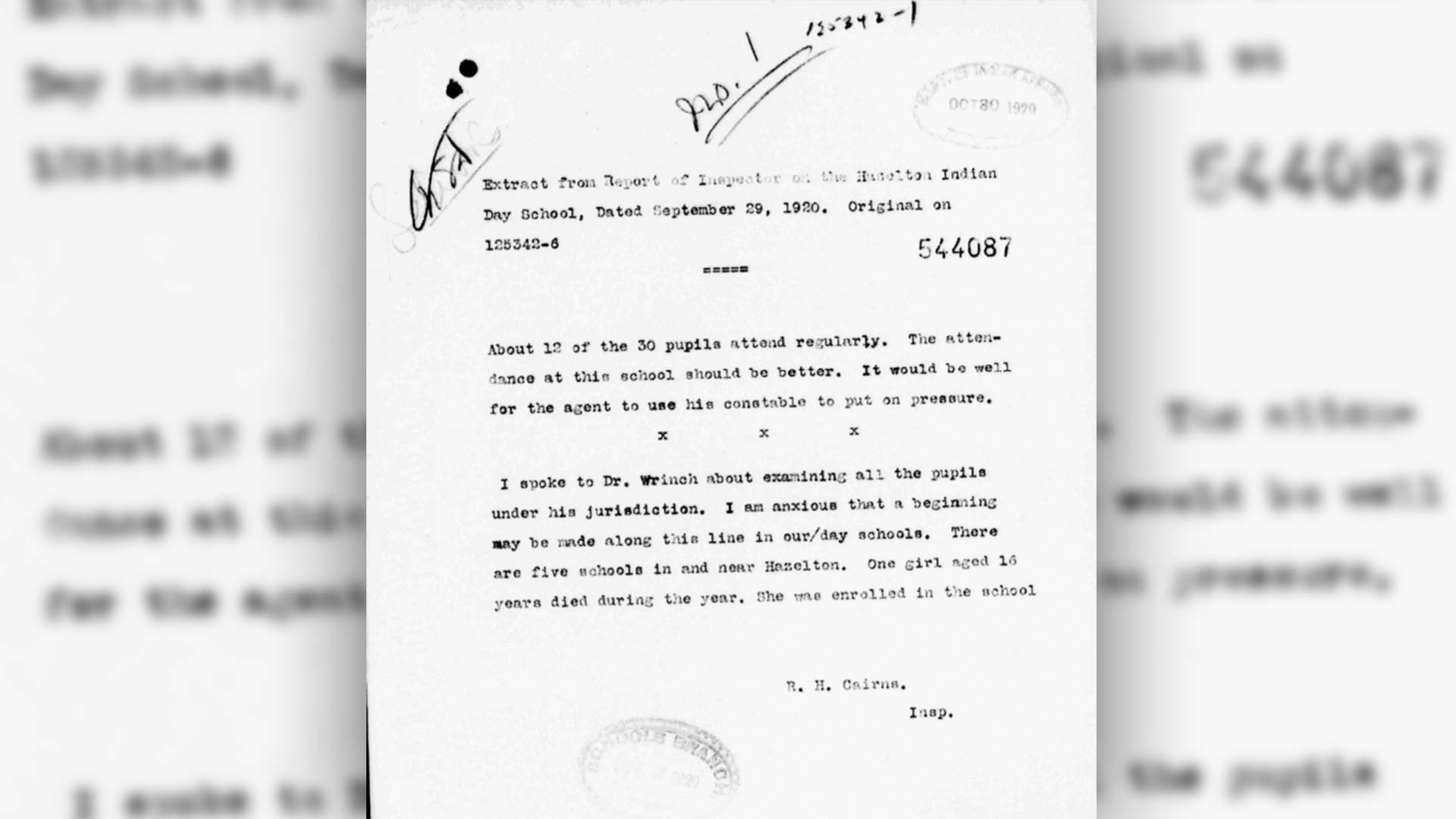

When attendance was down at the Hazelton Indian Day School in 1920, it was time to call in the police.

Historical documents obtained by APTN News show a federal inspector was concerned when only 12 of 20 students regularly came to school in northwestern B.C.

So he ordered the Indian agent for the area “to use his constable to put on pressure.”

What kind of pressure and applied to whom wasn’t explained in the documents APTN obtained from Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC).

The documents were received in response to an access to information request asking how many children died at provincially and federally run day schools. CIRNAC sent a partial dataset of records spanning 1916 to 1996 that included 46 schools.

That’s about 15 per cent of the nearly 700 day schools that operated in Canada from 1864 to 1996.

The records show 200 students died at the schools. Only two of the schools were provincially run at the time.

“My sister and brother used to get the strap,” recalled Donna Jack, a former student who survived two years at Ucluelet Day School on Vancouver Island.

“Maybe it was because they were speaking the language, but they weren’t allowed to talk about it.”

Day schools – often referred to as education centres and agencies in the documents – were run by non-Indigenous religious orders in partnership with the federal government.

Inspectors like the one at Hazelton were in charge until principals took over school administration in the 1960s.

The documents show inspectors relied heavily on the authority of Indian agents, who were federal employees in charge of imposing the government’s “Indian policy.”

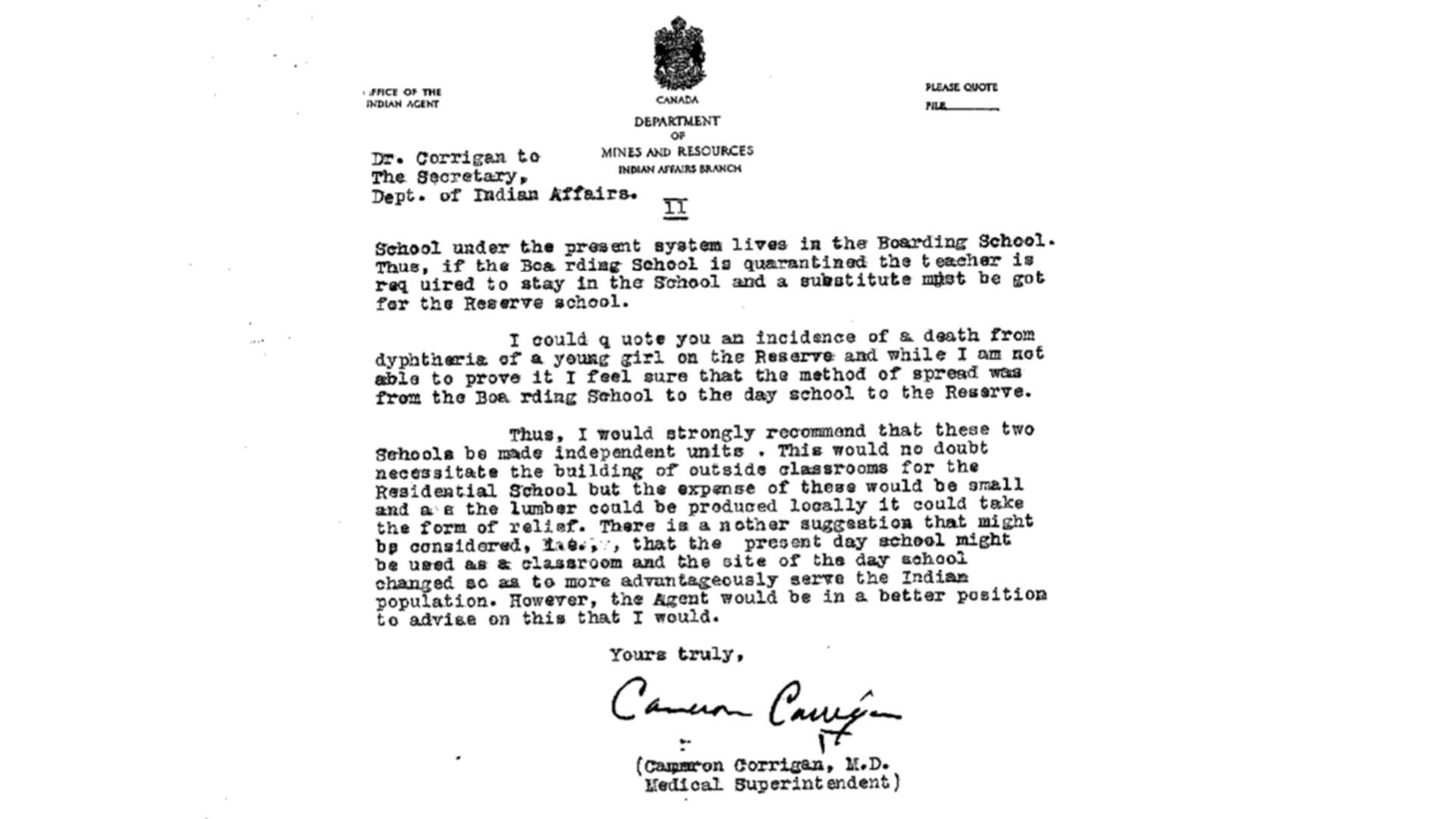

For example, an undated letter from a doctor to the Department of Indian Affairs shows the power Indian agents had over education, too.

Dr. Cameron Corrigan defers the decision to remove day school students from a residential school following the outbreak of an unnamed disease, even though he was the medical superintendent for the region.

Corrigan suggested “the present day school might be used as a classroom and the site of the day school changed so as to more advantageously serve the Indian population.

“However, the [Indian] Agent,” he wrote, “would be in a better position to advise on this that [sic] I would.”

It is well known thousands of students died in the residential school system, but the documents obtained by APTN officially reveal 200 deaths at 46 day schools.

That number could rise as more day school documents are released.

According to the documents, the biggest single killer of students in the 46 day schools was disease.

APTN received various school and student records showing when a death occurred and at which school.

One memo showed Indian agents were to be alerted to a student’s death even before the parents.

“When a pupil of an Indian Residential School dies, the Principal is required to inform the Indian Agent at once,” instructed a form about the death of student Donald Miller from Whitehorse Indian Day School on Feb. 22, 1951.

“On receipt of the Principal’s notice the Indian Agent shall convene a Board of Inquiry, consisting of himself as Chairman, the Principal of the Residential School, and the Medical Officer who attended the deceased pupil.”

The form said the Board of Inquiry would try to meet within 48 hours.

“The parents or guardians of the deceased pupil shall be given notice of this inquiry and be permitted to attend it or send a representative,” it continued.

“The inquiry, however, shall not be delayed more than 72 hours after the time at which it would otherwise be held, to enable them to attend it.”

The form noted the Indian agent could appoint a justice of the peace, member of the RCMP or provincial police [officer] to act on his behalf if distance made it “impracticable” for him to attend the hearing.

“If the pupil died as the result of an accident,” the form added, “the Indian Agent is required to take the statements of witnesses of the accident, and attach them to this memorandum.”

The form did not explain how student Miller died, how old he was, or whether his remains were returned to his family.

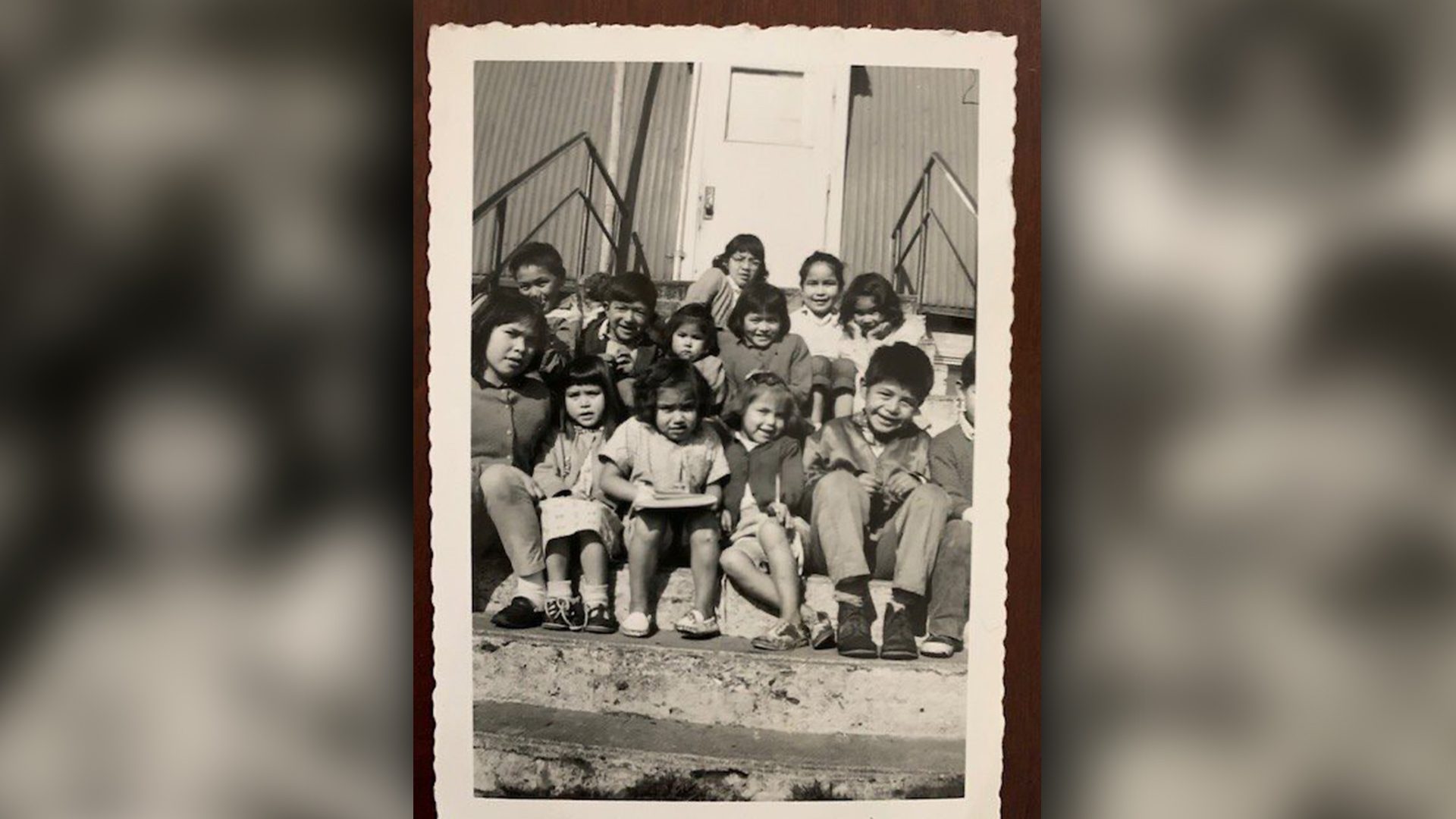

An estimated 200,000 Indigenous children were forced to attend the country’s 699 day schools, which included being sent to classes inside residential schools.

Day school students said they suffered the same physical, sexual and emotional abuse as residential students, even though they were allowed to return home at night.

That created a different kind of trauma for survivor Daniel Frank, who was forced to attend Ahousaht Day School on Vancouver Island.

“That was the hardest time of my life,” the Nuu chah Nulth man said in an interview with APTN. “I couldn’t tell my mom.

“If I told my mom bad news she’d just get mad at us. So I never ever told my mom.”

Frank said he kept it to himself when he was struck with rulers, chalkboard brushes and leather straps. He said he and other youngsters endured years of rape, abuse and torture.

But they survived.

Ten of the 200 student deaths revealed in the documents occurred at Frank’s school.

Frank said former day school grounds should be searched for unmarked graves.

This is the second in the three-part series Surviving Day School with APTN National News.