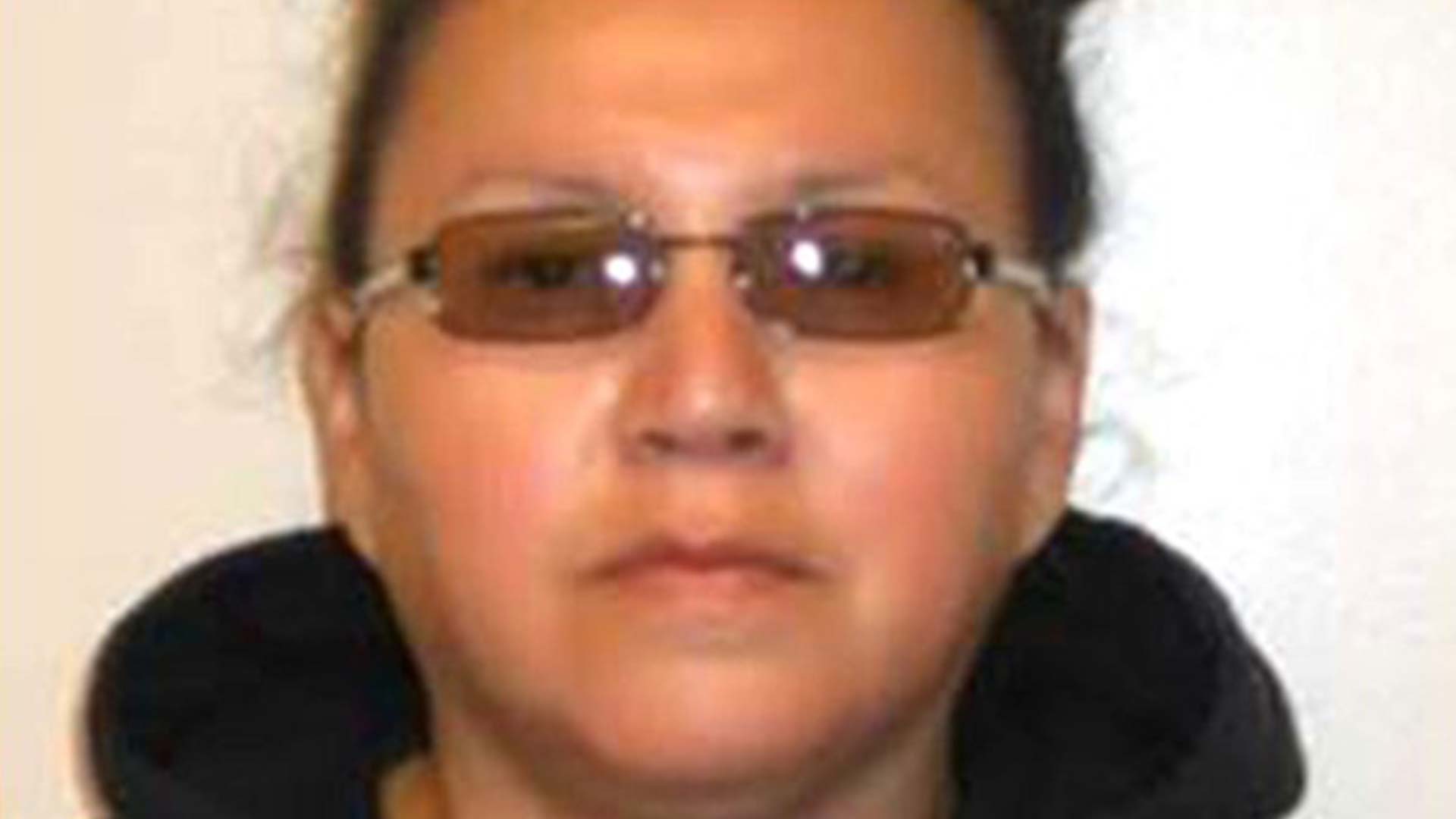

Harry LaForme says a miscarriage of justice commission is needed in Canada. Photo: Olthuis Kleer Townshend LLP

Two retired judges are putting their names – and their weight – behind the push to free two Saulteaux sisters from prison after 28 years.

Harry LaForme, the first Indigenous lawyer on an appellate court in Canada, and Juanita Westmoreland-Traoré, the first Black judge in Quebec, said the Parole Board of Canada (PBC) should “perhaps immediately” release Odelia and Nerissa Quewezance.

The women were sentenced to life in prison in 1994 after being convicted of second-degree murder in the killing of a white Saskatchewan farmer in 1993.

They have maintained their innocence throughout.

Their younger cousin told APTN Investigates he killed 70-year-old Anthony Joseph Dolff of Kamsack, served his sentence and has been released.

Jason Keshane, who was 14 at the time of the crime, was convicted of second-degree murder and sentenced to two years.

The development in the television documentary caught the attention of wrongful-conviction advocates across the country, who are lobbying federal Justice Minister David Lametti to review the case.

Now, the judges, who were appointed to lead an independent criminal cases review commission by Lametti, are adding their voices to the cause.

“We are familiar with the crushing impacts miscarriages of justice have, not just on the individuals but on their families, their communities and, we believe, the entire country,” LaForme and Westmoreland-Traoré wrote in a letter to the PBC tht was obtained by APTN News.

“We encourage the Parole Board to view the matter of the sisters as a case of potential wrongful conviction and approach it in a manner similar to that of the courts – to minimize harm.”

The judges said they see no value in keeping Nerissa, who is in custody in B.C., and Odelia, who is living in a federal healing lodge, behind bars. The women were 19 and 21, respectively, when they were convicted.

“If the sisters’ underlying convictions are vulnerable, isn’t their continued imprisonment equally vulnerable and wrongful?” the retired judges added in their letter.

“Should the Parole Board be encouraged to ask itself, ‘What is the public interest in their continued imprisonment and what does justice require?’ ”

The judges cited the pending application for a s.696.1 review of a potential miscarriage of justice from advocates for the sisters, who are from Keeseekoose First Nation, nine km north of Kamsack and 270 km northwest of Regina.

Because such reviews take years, the judges feel the sisters should be released “as soon as possible” pending the outcome.

“Canadian courts have recognized the injustice of continued imprisonment while such applications are investigated, eventually decided and where it is determined that a wrongful conviction occurred,” they said in their letter.

“They have granted bail pending the Minister of Justice’s final decision.”

The chair of the PBC, Jennifer Oades, said her agency has “exclusive authority” to grant, deny or revoke parole for offenders serving two years or more.

It can also make record suspension decisions under the Criminal Records Act, expunge convictions under the Expungement Act, and make clemency recommendations through the Royal Prerogative of Mercy (RPM).

But “the PBC does not have legal authority to unilaterally release individuals from prison other than upon applications for parole or at certain reviews in an offender’s sentence as prescribed by law,” she said in a reply to the retired judges – also obtained by APTN.

Oades said PBC members have guidelines when it comes to reviewing the case of an Indigenous person.

“Board members have a responsibility to consider any systemic and background factors that may have contributed to their involvement in the criminal justice system,” she said in her reply.

“The protection of society is the paramount consideration in all conditional release decisions, and the board is required to make the least restrictive determinations that are consistent with the protection of society.”

Oades further directed the judges to learn more about the clemency process under RPM by visiting the PBC’s website.

Meanwhile, Ian McLeod, a spokesperson for Justice, said the department “plays no role in decisions of the PBC, and cannot comment on parole issues.”

He said criminal convictions are reviewed by the Criminal Conviction Review group inside Justice, which advises the minister “on the appropriate remedy, if any.”

“For privacy reasons, we cannot comment on particular applications,” he added in an email to APTN.

There are no publicly available court documents related to the cousin’s trial because he was a youth at the time of his conviction and sentencing.

WATCH APTN INVESTIGATES’ A LIFE SENTENCE HERE

But he confirmed his guilt in an interview with APTN Investigates for the documentary A Life Sentence that first aired on Nov. 20, 2020.

The sisters have both been on day parole a number of times, but PBC documents show they repeatedly violated their conditions and lost their freedom. Their lawyer said they weren’t eligible for full parole because they won’t admit to the crime and show remorse.

Odelia last applied for parole 12 years ago.

She said she is grateful to the judges for arguing her case.

“I hope and pray that this letter makes a difference,” she said of the judges’ overture in a telephone interview.

“How much longer do I have to go through this knowing that my sister and I are innocent? I have spent 29 years now – day after day – waiting for someone to notice what is going on.”

Nerissa was arrested in July 2021 on a Canada-wide warrant for allegedly violating her parole conditions.

READ MORE: Legal advocates to petition justice minister to overturn sisters’ murder convictions

The Quewezance sisters are two of a “disproportionate number” of people of colour in Canada’s prisons, added LaForme in a telephone interview Wednesday, “most of which relate to the country’s colonial history or circumstances beyond their control.”

He said Indigenous women, specifically, comprise “the fastest-growing population in Canada’s prisons.”

Statistics provided by the Office of the Correctional Investigator show Indigenous Peoples account for roughly five per cent of the population yet Indigenous women make up 42 per cent of women in federal custody.

LaForme, who is Anishinabe and a member of the Mississaugas of the New Credit First Nation in southern Ontario, said he learned about the sisters’ case in the midst of 40 virtual meetings he is chairing with Westmoreland-Traoré as part of the work on a criminal cases review commission. He said he was advised to write a letter to the PBC on their behalf.

“Through this process it has been expressed to us that the public is aware of, and appalled by, what these sisters are experiencing here in Canada,” he said.

“They have been locked up for 28 years, have not seen each other for most of that time, and the person responsible for the crime they were convicted of has confessed.”

Odelia said the judges’ words give her hope.

Finally listen

“Hope that someone will finally listen to us,” she said over the phone.

“How much is it going to take? Two judges have now said that we should be released, and they are – what would you call it – high profile, so if they aren’t going to listen to them, who are they going to listen to?”

The sisters’ advocates include Innocence Canada, a non-profit organization that identifies people who have been wrongfully convicted, and David Milgaard, who was exonerated by DNA evidence in 1997 of raping and murdering Saskatoon nurse Gail Miller in 1969.

Milgaard served 23 years in prison before being released in 1992, while awaiting the outcome of his case review. He was offered a chance at parole many times but refused to admit to a crime he didn’t commit.

The Congress of Aboriginal Peoples, which represents those living outside Indigenous communities, first took up the sisters’ cause earlier this year.

Editor’s Note: The original story said the sisters were from Cote First Nation. They are from Keeseekoose First Nation.