Angelica Casimer is the daughter of residential school survivor Gerald Casimer. Photo courtesy: Angelica Casimer

When Angelica Casimer wrote a moving tribute to her father – a residential school survivor – in 2017 she had no idea it would go viral in 2021.

“My post has been shared over 30 thousand times. It has reached across the world and has been translated into different languages,” the married mother of two said from Kelowna, B.C., Monday.

Nor did she know it would help so many people process the recent discovery of nearly 1,000 unmarked graves at two of Canada’s former government boarding schools.

“I think we may have changed the narrative, but I’m devastated that it took finding the remains of 215 little souls for this to happen,” she added.

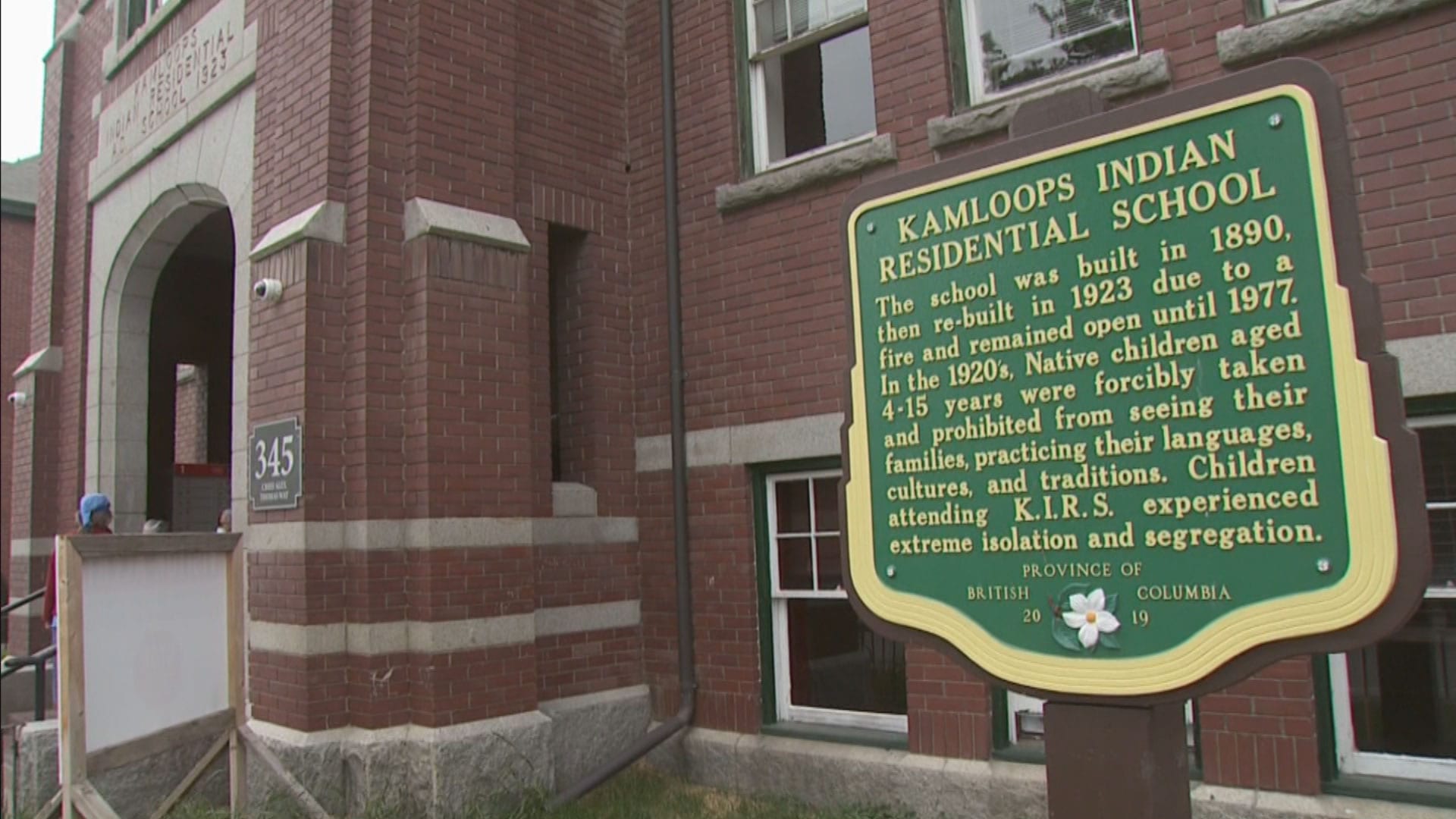

Casimer, a Saik’uz woman from north-central B.C., originally wrote the piece to honour Gerald Casimer, who was forced to attend the Lejac and Kamloops schools in B.C.

“Most of our parents, grandparents were kidnapped and raised in residential schools. Yes, I said kidnapped because they were forcefully taken, and torn from their families at a young age to be assimilated. These innocent and vulnerable young children were hunted by the Indian agents and rcmp, handcuffed and transported to residential schools like cattle,” Angelica wrote in the essay that can be read here.

“I wrote it when I was going through my own healing process,” she explained. “That’s when it occurred to me that my beautiful, wonderful father was the first person – in, I don’t know, how many generations – to raise his own children.”

Angelica’s two sons were 10- and three-years-old in March 2017 when she first penned the essay.

“If I was born 50 years earlier, my children would have been taken away from me.”

The words have now taken on additional meaning for her and others who have found it online following the discovery at the Catholic-run school sites in Kamloops, B.C., and Cowessess First Nation in Saskatchewan.

Sadly, Gerald died in December 2020 – before the graves were found.

But Angelica said the 82-year-old knew children were buried there.

“He did remember cousins and friends disappearing. Going to the infirmary and never coming back,” she said.

“He remembers a priest making him dig a hole at Lejac.”

Gerald also knew there was a graveyard at Kamloops, Angelica said.

“They [didn’t] really talk about it. Being a child in a house full of survivors you listen and you pick up stories and you hear it and hold onto it.

“I knew not to bring it up.”

Angelica said she came to understand “just how incredibly powerful and strong and resilient our elders and survivors really are.”

An estimated 150,000 First Nation, Metis and Inuit children were taken from the families – their parents threatened with arrest if they resisted – and put into the system.

Gerald was the oldest and Angelica said he shared little about his time at the schools.

“He had six siblings. All of them went to residential school, but it’s all agreed upon that my father and his three younger siblings had it the worst.”

Angelica said Gerald recounted being dragged behind a pickup truck.

“He and his younger brother, Bert, were doing jobs for the priests down by the lake during the wintertime, and they were starving. So the priests thought it would be fun to tie them – put skates on them – and tie them to the end of the truck and drive around on the ice. And their compensation for that was to share a sandwich,” she said.

“I was blown away by what these priests were capable of.”

Another time he said he was electrocuted by the head priest at Kamloops through the use of an in-house device.

“It had two handlebars that he held onto. And they turned it up and he couldn’t let go.”

Angelica said her father developed a stutter from the abuse and talked about it during his application for compensation through the 2006 Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement (IRSSA).

The class-action settlement, which expired in 2012, was the largest in Canadian history. It created a $1.9-billion compensation package to recognize the damage inflicted by the schools, a healing fund, and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC).

The TRC’s final report in 2005 detailed what happened to many of the children, including physical, sexual and emotional abuse. It estimated 3,200 children died from tuberculosis, malnutrition and other diseases resulting from poor living conditions.

Now, Angelica is adding the voice of children of survivors to the national conversation.

“From the messages and comments I’ve received, the [essay] has struck a chord with people and opened up a new understanding as to the abuse and intergenerational trauma that affects my Indigenous peoples to this day.”

She said touring the former Kamloops school, on the traditional territory of the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc, a few years ago helped inform her writing.

“I snuck off and I went upstairs to imagine what my dad went through. I was angry,” she said, “with different kinds of anger.”

The Indian Residential Schools Resolution Health Support Program has a hotline to help residential school survivors and their relatives suffering from trauma invoked by the recall of past abuse. The number is 1-866-925-4419.