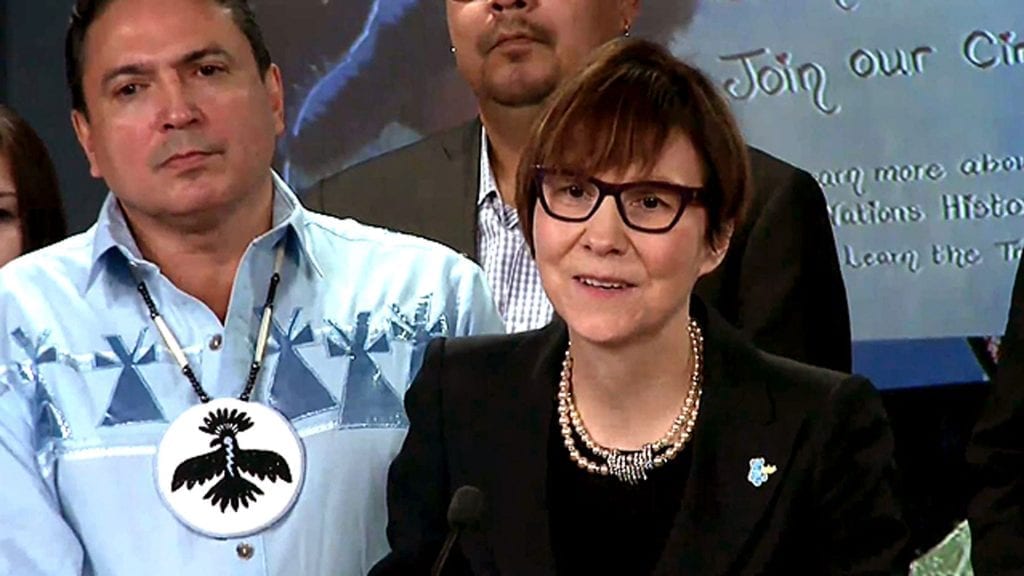

Cindy Blackstock and National Chief Perry Bellegarde after the human rights tribunal issued its 2016 decision. Photo: APTN

The federal government kicked off the first of two Federal Court appeals on Monday by arguing a Canadian Human Rights Tribunal order that compensates First Nations children harmed by the state’s racial discrimination is “so deeply problematic” and “seriously flawed” it must be, if not quashed altogether, sent back to a new tribunal for reconsideration.

“Canada has acknowledged the need to reform its child welfare policies and programs — and to recognize the fact that the old policies and programs caused harm,” said chief general counsel Robert Frater, one of the Justice Department’s top lawyers, as he introduced Ottawa’s case.

“Canada has also recognized a need to compensate the children affected,” he added, “but the need to acknowledge past harms, to redress the wrongs, to prevent them from happening again does not justify the orders at issue in these judicial reviews.”

Those orders were handed down in 2019 and 2020 respectively, though the case dates back to 2007, when the Assembly of First Nations (AFN) and the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada (Caring Society) lodged a complaint with the Canadian Human Rights Commission.

They complained that Indigenous Services Canada’s — then known as Indian Affairs — “drastic under funding” of the First Nations child and family services (CFS) program racially discriminated against First Nations kids.

Ottawa reporter Brett Forester breaks down the appeal:

In 2016, the tribunal issued its landmark “merits decision,” which concluded the First Nations CFS program and Ottawa’s refusal to enact Jordan’s Principle were indeed violating basic human rights and discriminating against First Nations children on reserves and in the Yukon.

Jordan’s Principle exists to prevent jurisdictional disputes between governments about who will pay for essential services for First Nations kids, stating the government first contacted must pay for the product or service required and discuss the bill later.

The quasi-judicial tribunal panel ordered Canada to reform the First Nations CFS program and apply Jordan’s Principle to all First Nations children, an order Canada did not appeal.

In 2019, the tribunal awarded the maximum allowable amount of $40,000 to kids and families for the infringement of dignity that results from human rights violations.

The panel said Canada’s “wilful and reckless” racial discrimination was “a worst-case scenario” under the Canadian Human Rights Act — factoring into children’s suffering, pain and even some deaths.

In 2020, the panel concluded Ottawa still wasn’t applying Jordan’s Principle to all First Nations kids. They ordered Canada to broaden eligibility to certain non-status First Nations kids who live off reserve. (Canada will argue on this later in the week.)

The crux of Frater’s argument was that the compensation order was unreasonable, unsupported by evidence and veered too far away from the original complaint about discriminatory funding practices, making findings that were unsupported by both the record before it and the human rights act.

He argued the tribunal’s “seriously flawed” reasoning lacked proportionality because it awarded the maximum amount to all kids and family members without differentiating the scope and nature of their suffering.

“The tribunal in this decision painted with broadest of brushes. For the tribunal, again, every case is the worst case for both First Nations kids and their parents,” Frater said.

“There is no evidence to justify this. No logic justifies that. But giving the maximum magically makes the evidentiary problem go away.”

Frater blasted the tribunal for its “simply fallacious” reasoning and procedurally unfair “straw man attempts” to reject Canada’s legal positions.

The tribunal concluded Canada’s discrimination is ongoing, something Frater contended was totally wrong given the billions Ottawa has spent reforming the on-reserve child welfare and Jordan’s Principle programs.

“The decision here is so deeply problematic; the process that was adopted is unacceptable,” Frater said. “It would be better to start again with another tribunal on this discreet issue (of compensation).”

The presiding judge is Paul Favel, a member of Poundmaker Cree Nation in Saskatchewan who was appointed to the bench in 2017. Favel was formerly a partner at a law firm in Saskatoon and specialized in Aboriginal law, acting as counsel to various First Nations.

Favel has been managing the proceedings since 2019 and presided over Canada’s failed bid to pause the compensation order until the present hearing.

The judge jumped in at a few opportune times to ask Ottawa’s lawyer to clarify his points. Favel also asked Frater to respond to the Caring Society and AFN’s argument that Canada is conducting a back-door assault on the 2016 decision and subsequent decisions it has already accepted.

Frater insisted Ottawa is not mounting a “collateral attack” on past rulings. He said Canada accepted all rulings it believed held true to the original complaint, which was about systemic discrimination. The complaint asked for $112 million to be placed in a trust and not individual payouts that will cost billions, he argued.

This was a major point in Canada’s written arguments, which claimed the tribunal had lost sight of the original allegations and turned the hearing into an open-ended, indeterminate set of proceedings.

“That why we’re here today. It’s the changing of the nature of the case,” said Frater. “We can challenge that decision (to compensate) without collaterally attacking the merits decision or any of the others.”

An unconvinced-looking Anne Levesque, counsel for the Caring Society, shook her head from time to time as she listened.

Her colleague Sarah Clarke, with the white Spirit Bear behind her, eagerly rebutted Canada’s arguments, accusing Ottawa of launching a misguided, 11th-hour appeal that ignores the suffering children experience on the ground.

“Once again, Canada is attempting to provide legalistic, technical and ultimately irrelevant context to a decision that impacts a child,” she said.

“Canada’s arguments in this regard are not about advancing the rights of First Nations children or protecting the rights of victims. Instead, these arguments reflect a shameful strategy aimed at saving money at the expense of First Nations children and families across the country.”

Clarke argued that the tribunal’s decision to compensate was “internally coherent,” logical and at no point exceeded the boundaries of the human rights act.

She said human rights compensation is meant to be a “one-two punch,” in which damages ought to flow once a complaint is substantiated, as this one was.

“Rough justice,” she added, is an important human rights tool that is required to punish and remediate discrimination. She suggested some “rough justice” may be needed to ensure Canada learns a lesson.

“When Mr. Frater said today that this is a massive compensation order, he’s not wrong. But it’s only massive because of Canada’s widespread discrimination,” said Clarke.

“To seek to avoid financial liability because it is systemic and so widespread tells us that Canada has learned very little from the lessons of residential schools, the ’60s Scoop and has not spent the requisite time reflecting on the stories and the guidance provided by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.”

The judicial reviews are happening in a charged political atmosphere after the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation reported on May 27 that it had confirmed the existence of an unmarked burial site containing what it believed to be remains of 215 children at a former residential school in Kamloops, B.C.

A week later, the House of Commons passed a unanimous motion demanding Canada drop these appeals.

Though legally non-binding, the motion was passed with support of all parties. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, his cabinet and some of their key lieutenants all abstained, however.

The NDP said the vote expressed clearly the general public’s desire to end this legal wrangling.

“I am disappointed that we are here today, once again asking the government to stop denying Indigenous children the compensation they are owed,” said NDP MP Charlie Angus in a Monday press release. “They are defying the will of parliament and the will of Canadians by continuing these cruel proceedings.”

At a press conference Monday morning, Indigenous Services Minister Marc Miller suggested litigation like this, when the legal issues are “immensely complex,” is an unfortunate but necessary bump on the road to reconciliation.

“It’s slow and often painful and today is one example of that. We’ll let the proceedings play out in court, but we’ll make sure at all times we’re being respectful in our representations,” he said.

“Sadly, it has come to a review of a court case with respect to which there are disagreements. It doesn’t mean that we can’t move at the same time along compensating children or moving along systemic reform.”

Clarke will resume for the Caring Society on Tuesday followed by the AFN.

The Chiefs of Ontario, Canadian Human Rights Commission, Congress of Aboriginal Peoples and Amnesty International are scheduled to argue on Wednesday.

The Jordan’s Principle appeal will be heard Thursday and Friday.

First Nations children make up only seven per cent of the general population yet constitute 52 per cent of children in foster care. There are currently more kids in state custody today than at the height of the residential school era, according to government figures.