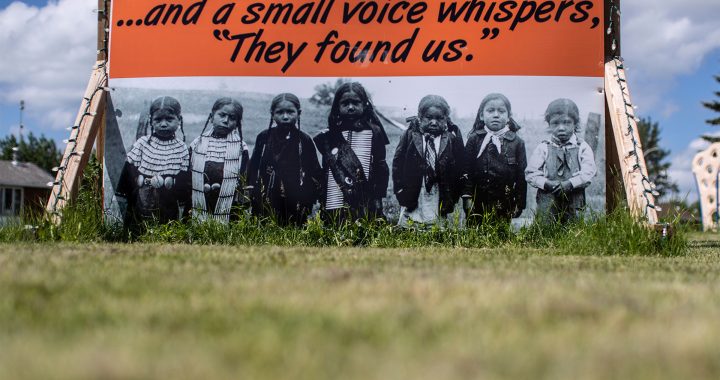

Due to colonization and a legacy of racist policies, Indigenous families are grossly overrepresented in Canada’s so-called child-welfare system. Photo: Brielle Morgan/IndigiNews

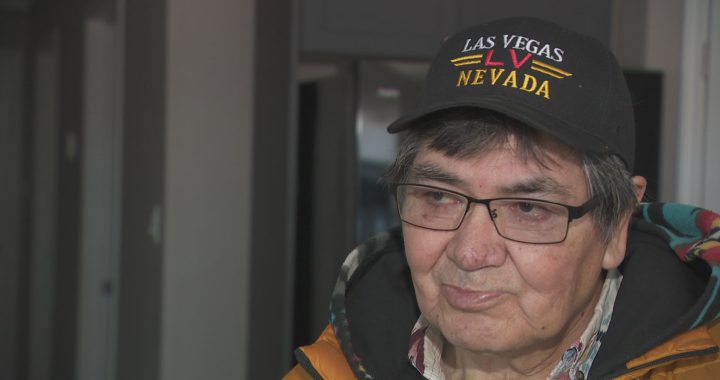

Raymond Shingoose — whose spirit name is Tipiskoh kee see koowihnin (man standing between heaven and earth) — has spent decades working to assert Indigenous children’s rights.

When he was 12, he was taken from his grandparents’ care as part of the Sixties Scoop.

“We lived the traditional ways and I got taken away because of that. And I think that’s wrong,” says Shingoose, who is Anishinabek and comes from the Cote First Nation. “We’re still apprehending children because of poverty.”

Today he’s one of many calling on Canadians to move beyond notions of neglect rooted in racist, colonial ways of thinking and doing.

Last week Shingoose shared his wisdom as part of Beyond Neglect — a series of six online talks organized by the Child Welfare League of Canada (CWLC), featuring speakers with lived experience and expertise on the so-called child-welfare system.

The goal was “to brainstorm ways we can better meet the needs of all children, youth and their families so we can keep families together in the community, and out of the child protection system as much as possible,” says Melanie Doucet, senior researcher and project manager for the Child Welfare League of Canada (CWLC).

Doucet estimates that “a few hundred folks” attended each of the six sessions. She says CWLC will release a report in the coming months, “summarizing the series and presenting the outcomes from our discussions.”

In the meantime, here are our takeaways:

Need to move beyond blaming parents

In many countries, including Canada, neglect is the most common type of maltreatment, says Monica Ruiz-Casares, an associate professor in the psychiatry department at McGill University.

But what exactly is neglect? According to Ruiz-Casares, it’s pretty subjective.

“There’s no clear threshold at which so-called poor parenting crosses the line into neglect,” she says.

In Canada, neglect is largely defined as “the failure of the parent or the guardian to provide the child’s basic needs” such as food, education, supervision and health care, she says.

The focus is on a parent’s perceived weaknesses rather than “the social, economic, political and other contextual circumstances that contribute to parenting.”

A more systemic view of neglect “focuses on the child and goes beyond parents, families and communities … to also include the role and responsibility of society and the state,” she says.

It would include “considerations of entrenched inequalities, poverty and inadequately resourced support services and other legacies of colonialism.”

It would ask: To what extent are parents supported? Are we actually talking about parental neglect — or governmental neglect?

“[The] relationship between poverty and child protection placement is particularly powerful for highly marginalized populations including Indigenous, Black, racialized, and migrant families, who have experienced systemic discrimination, racism, and genocidal policies,” reads a briefing paper prepared for the Beyond Neglect series.

We need to do a better job of listening to parents and youth, Ruiz-Casares says. Too often, we dismiss their views, and this “prevents us from understanding the real causes of neglect.

“The scientific literature on child neglect is largely focused on the inadequacies of families, the shortcomings, and rarely includes their perspectives, and even less the perspectives of young people.”

Nistawatsiman

Gabrielle Lindstrom (nee Weasel Head) is a member of the Kainaiwa Nation.

She works as an educational development consultant at the Taylor Institute for Teaching and Learning at the University of Calgary, and she specializes in Indigenous ways of knowing.

She spoke about nistawatsiman — “a Blackfoot word which means rearing children with all the traditional teachings of our people … [including] compassion, harmony, trust, respect, honesty, generosity, courage, understanding, peace, protection and knowing who your relatives are.”

Lindstrom says she learned about nistawatsiman from Elders in the Blackfoot Confederacy as part of a 2016 research project she carried out with Peter Choate, a professor of social work at Mount Royal University. Together they looked at how Indigenous parents are assessed by child protection workers.

“The Elders helped us to define what family means for Blackfoot Peoples,” she says. The project also “highlighted how the use of Eurocentric definitions of family are insufficient, as they do not capture the reality of First Nations peoples.”

Decisions to apprehend children are too often driven by racism and neocolonialism — or “the use of economic, political, cultural or other pressures to control or influence Indigenous nations,” she explains.

“Neocolonialism reveals a set of distinct Eurocentric cultural values, premised on individualism, free markets and notions of universal definitions that are embedded in philosophical assumptions that inform how social systems operate.”

Tools used to assess families in Canada are rooted in these Eurocentric ways of thinking and being, she says.

For example, the genogram is “a narrow tool that does not consider the broader definition of family that can extend beyond biological ties,” she says.

And parenting capacity assessments are also problematic, she says. These are used, according to the briefing paper, “to determine a parent’s ‘capacity’ to raise their own child, if intervention is needed to support parents to meet parenting capacity requirements, or if it is probable that parents cannot raise their child.”

These assessments “do not consider the role of the Indian residential schools and the disruption that these schools have for Indigenous families,” Lindstrom says.

Raji Manjat also called out parental capacity assessments for being “very flawed in their methodology … not at all normed around … Indigenous caregiving, Indigenous families and Indigenous wellness.”

Manjat is the executive director of West Coast LEAF, a non-profit organization located on the unceded homelands of the xʷməθkwəy̓əm (Musqueam), Skwxwú7mesh (Squamish), and Səl̓ílwətaɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) peoples in so-called Vancouver that uses legal strategies to address gender-based discrimination and inequities.

So much of what happens inside the child-welfare system is “based on exercises of discretion that are largely unseen and unstructured and don’t have accountability built into them,” says Manjat.

“There’s a lot of variation, in terms of how the rules — how the laws are even understood within systems actors’ minds.”

Newcomer families misunderstood as neglectful

Parents who have recently migrated to Canada with different cultural norms are too often mislabelled as neglectful, says Ruiz-Casares.

As part of an ongoing research project, she’s been studying how adequate child supervision is defined across diverse cultures and socioeconomic groups in Quebec. She says different cultures have different norms.

For example, in some cultures it’s normal for parents to hire babysitters, whereas in others parents may rely on older children as caregivers for younger siblings.

In Quebec, she says the idea that kids are being “locked in” because they’re largely kept indoors and close to adults was “repeatedly mentioned” by study participants.

Ultimately, researchers found that because practices of immigrant families are being misunderstood as neglect, “some caregivers were afraid to be mislabelled as irresponsible caregivers or reported to youth protection by neighbours or community members.”

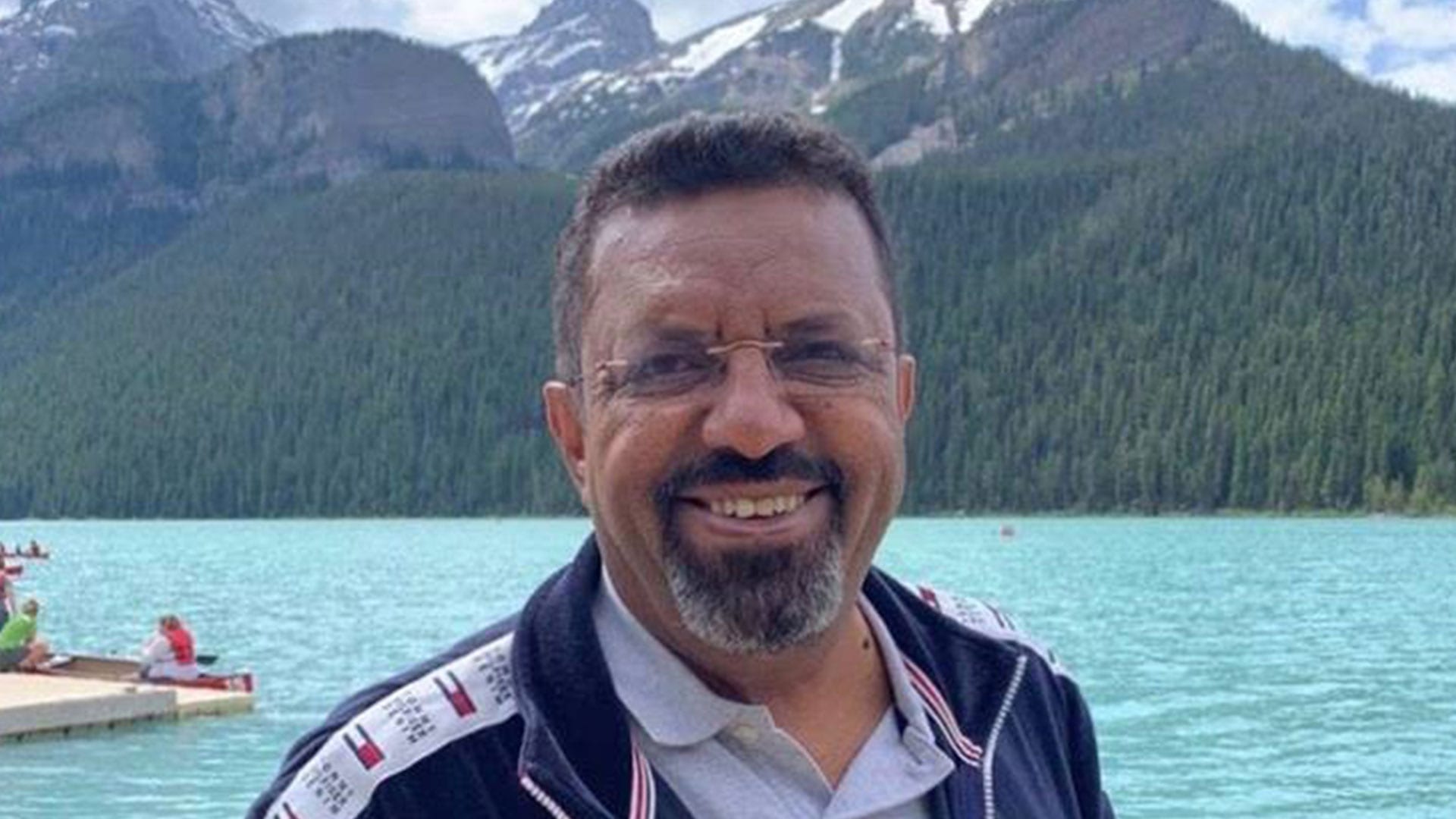

Mohammed Baobaid also spoke to the importance of recognizing and valuing different worldviews.

He’s the founder and executive director of the Muslim Resource Centre for Social Support and Integration in London, Ont., and he’s developed a culturally-integrative model of family-violence responses based on 30 years of researching families, children and youth at risk in Yemen and Canada.

In Baobaid’s view, Canada’s child-welfare system is more concerned with protecting the individual than protecting family unity.

It asks how can we protect this child, as opposed to how can we preserve this family? Bridging the gap between these worldviews can be hard for newcomer families who come from a “collectivist background,” says Baobaid.

“Imagine if you’re a child or a woman … On one hand, you want to get protection, but on the other hand you don’t want to be seen by your family as someone who’s bringing problems to the family.

“We need better communication between these two systems,” he says, adding that the key is to better support families by recognizing and building on their strengths.

‘Old, white men’ created this system

Irwin Elman served as Ontario’s child and youth advocate for ten years before his office was shut down by the province’s Progressive Conservative government in 2019.

Like Baobaid, Elman emphasizes that when it comes to the well-being of kids and families, Canada focuses on “protection” — to its detriment.

“I don’t think we have a child-welfare system. We did not create one. We created a child-protection system, so we should not fool ourselves,” he says.

By “we” he means “old, white men,” and he was careful to underscore this again and again.

“The idea started back in 1642, in Massachusetts,” he says. “Judges in 1642 had the authority to remove children from their homes in order to … ‘turn them out properly.’

“Then in 1875, we created in New York the first Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children,” he says, adding — pointedly — that this followed the establishment of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals in England in 1824.

“That was the first kind of child-saving,” he says.

“We — people like me — were worried about homeless children. We were worried about rising crime rates … we worried about immigrants coming to ‘our country’ who would not be able to bring their children up right. They wouldn’t be able to turn them out right.

“They would not be — and this is a quote from the States and Canada — they would not be ‘productive citizens,’ meaning they wouldn’t be good employees. We created this white savior scaffolding, he says. And then we built on it.

“The system we created has not changed,” he says. “We have laws that are designed to protect children, and remove children when they need protection. Why? Because we think that safety is in separation.

“We can’t stop thinking that way because we are taught and grow up and think that way,” he says. “Which is why I so strongly support First Nations, Indigenous people, Inuit, Métis, creating their own … systems.”

When asked what advice he has for child and family advocates working in the field right now, Elman says, “Just listen — I know that sounds trite, but … you can create change just by listening, because in listening you’re validating their experience.”

Asserting inherent Indigenous rights

Vice-Chief David Pratt is serving as an executive member for the Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations (FSIN), a Treaty and Inherent Rights organization that represents 74 First Nations.

He says in order to understand today’s child-welfare system people need to look back — way back to Canada’s confederation.

“The ink wasn’t even dry on the treaty documents and the [John A.] Macdonald government was already working on the Indian Act and legislation meant to control us paternalistically in every aspect of our lives,” says Pratt, who is a member of Muscowpetung Saulteaux First Nation.

“Taking our children away under the threat of the RCMP (the North-West Mounted Police prior to that) to enter these [residential] schools where they’d be gone for 10 months out of the year, away from their parents and grandparents … many times under the threat of jail if they did not give up their children.

“There began the dysfunction, and a lot of where we are today.”

He points to the steep rise in the number of Indigenous children in foster care after section 88 was added to the Indian Act in 1951, passing responsibility for Indigenous child welfare from the federal government to the provinces.

“Of course, that number rose significantly through the ‘50s, ‘60s, ‘70s, ‘80s and led us to the numbers where we are today,” he says.

This assault on Indigenous families spurred Indigenous leadership into action, Pratt says.

He says decades of Indigenous-led work to assert responsibility over children in care culminated recently in the passing of Bill C-92, an Act respecting First Nations, Inuit and Métis children, youth and families, which came into force Jan. 1, 2020.

While it may not be “a perfect piece of legislation,” he says, “it recognized First Nations’ jurisdiction.”

Shingoose, who’s worked closely with Pratt and others to bring change in Saskatchewan, says C-92 seems to create an opportunity for First Nations to “assert our inherent rights.”

He sees good, bad and unknowns in C-92, he says, and it’s also missing something — the eradication of section 88.

“That would be the true assertion of our inherent rights, and I don’t see it in C-92.”

Going forward, Pratt says we need systems “created, directed and managed by First Nations people to ensure the protection and safety of their people, based on their own inherent rights, policies, laws, beliefs and customs.”

And the federal government needs to “substantially and significantly” increase funding for the implementation of C-92.

“We want to protect the rights of our First Nations children to live with a First Nations family,” says Shingoose. “That’s our ultimate goal.”