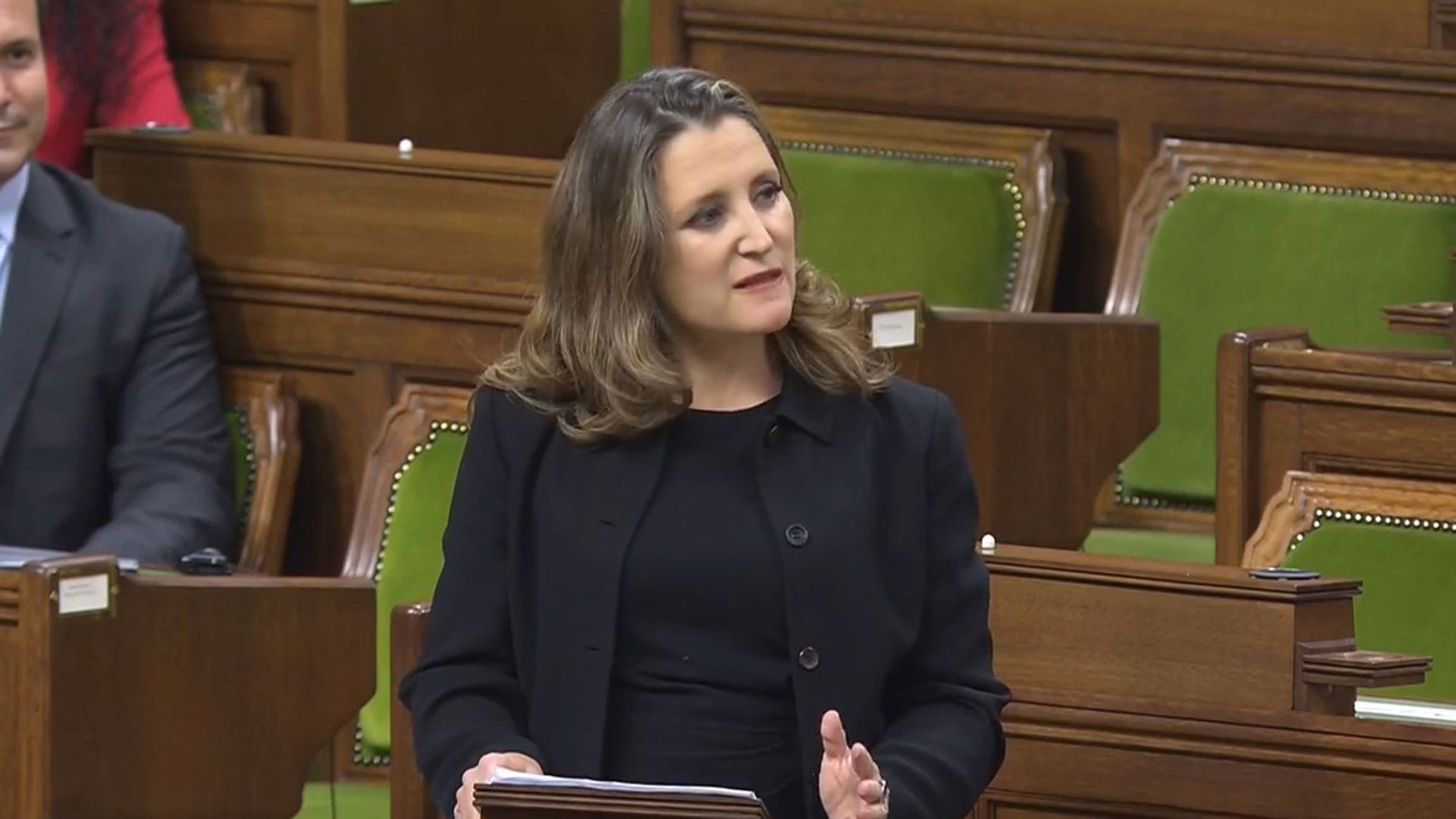

Chrystia Freeland will deliver her first budget as Finance minister on April 19 in the House of Commons, located here in West Block on Parliament Hill. Photo: APTN

Indigenous people, organizations and businesses will be looking for Ottawa to deliver on core issues like clean water, housing, health care, economic development, child welfare reform and ending systemic racism when Justin Trudeau’s Liberals table the federal budget for the first time in two years on Monday.

The feds basically tossed the books in the fire when the pandemic shut the country down in March 2020. They spent more than $300 billion through the crisis, racking up a deficit projected to be the largest since the Second World War.

For some, the government’s willingness to shovel that much cash out the door to combat a crisis stands in stark contrast to crises that have persisted in some Indigenous communities for decades.

“This country had billions to spend and millions to spend to combat a pandemic,” says Cathy Martin, an elected councillor at Listuguj in Quebec and education director at Walpole Island in Ontario.

“They certainly have the resources, we have the resources in Canada to ensure that clean water is taken care of, whatever the cost.”

She and others who shared their views with APTN News say it’s time Liberals start delivering on their promise to close the gap.

“Whatever the price tag is, is irrelevant. The fact remains that Canada had the financial resources to make it happen,” says Martin. “Whichever government holds the purse strings, they need to make that happen.”

Water is one of many issues. The government took some heat for failing to end all long-term, on-reserve drinking water advisories by a self-imposed deadline of March 31, 2021.

Ottawa is nearly a year late with an action plan in response to the missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls inquiry.

Housing crises in the North and on reserves persist and even worsen. The pandemic exposed gaping inequities in health-care services that Indigenous and non-Indigenous people receive.

“We’re so underfunded in every department. To prioritize which one would be ideal, right now, is hard to do because the needs are so many,” says Martin.

“But we have to start with the basic humanities of life, like water and being respected as human beings.”

Indigenous departments seek estimated $18B

Shannin Metatawabin offers a similar take. He’s the CEO of the National Aboriginal Capital Corporations Association (NACCA), which fosters Indigenous business development.

NACCA administered a $300-million government stimulus package to help pandemic-struck Indigenous businesses that, he says, already face systemic and legislative barriers.

He’ll be looking for Ottawa to keep up the investment.

“Our people are locked in this social trap where the government is only thinking about the social spend,” which could hit $18 billion this year, says Metatawabin.

That’s according to the Indigenous departments’ pre-budget estimates. Only the Defence Department wants more.

Metatawabin explains that this sum is twice what it was 15 years ago. He projects Indigenous spending needs could double yet again over the next two decades, so he’s urging Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland to start planning now.

“It’s a very unsustainable sort of trajectory,” says Metatawabin. “I’m trying to really call out government on the need to invest in Indigenous economic development.”

He agrees with Martin that the Liberals need to show “a real commitment” to getting things done. That means no more delaying issues they’ve campaigned on.

Freeland and Trudeau have defended the government’s wild emergency spending as “low cost capital” that’s easy for the feds to borrow — and justifiable under the circumstances.

Metatawabin wonders where that thinking has been when Indigenous communities have found themselves in dire need of life-saving, emergency cash.

It’s been said that Nunavut’s housing crisis requires an immediate injection of $2 billion, while the Assembly of First Nations estimates child welfare reform needs $3 billion.

Both situations have, separately, been termed a humanitarian crisis.

“Why can’t that same rationale be used for closing the Indigenous gaps in health, education and business?” Metatawabin asks.

He points out the Black Lives Matter movement has pushed systemic racism into the spotlight and forced public institutions to reckon with issues Indigenous people have been shouting about for a very long time.

“If this focus on closing the gap and getting rid of systemic discrimination is truly, really serious then they should put the money and resources (there) to ensure that they actually make everything equitable,” says Metatawabin.

“Every Canadian should have access to the same services.”

National orgs pleased with 2020 money

The national Indigenous organizations lauded the 2020 throne speech and keystone new cash rolled out in lieu of a budget.

This included:

- $2 billion for pandemic support for Indigenous communities

- $1.5 billion to help lift remaining boil water advisories

- $781.5 million (over five years) to fight violence against MMIWG and LGBTQ2S people

- $542 million to continue with child welfare reform

Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami has released its pre-budget submissions, which revolve around addressing that aforementioned “crippling infrastructure deficit.”

Pauktuutit, the national Inuit women’s organization, says it wants new money for Inuit-specific shelters and second-stage transition housing for women and children fleeing violence.

In its pre-budget submission titled “Maintaining Momentum,” the AFN asks for $6.8 billion for education and $4 billion for housing.

The Métis National Council hasn’t released it’s pre-budget asks but welcomed the fall investments.

Regular Indigenous folks who shared their views with APTN seconded supplying reserves with clean water — “this year, not in five years” — as a top priority.

They were also concerned with high rates of incarceration and child apprehension as well as the dire need for reform to the health, justice and policing systems.

The Liberals have started all this work but still have a long way to go.

They’ve introduced legislation to roll back mandatory minimum sentences, started consultation on making First Nations policing an essential service and kicked off the co-development process for health-care reform legislation.

Others want to see the feds finally compensate kids harmed by the state’s discriminatory CFS system on reserves and in Yukon.

Ottawa has promised to pay the victims, but that promise has yet to be reflected in any budget.

Deep deficit, steep climb

The economic crater has some financial experts, banks and pundits wringing their hands worrying about how, or if, Ottawa plans to balance the books.

Ian Lee, an expert and associate professor with Carleton University’s Sprott School of Business, says the first thing he’ll be watching for is the actual deficit.

The budget office forecasts it may be $363 billion. Federal debt could surpass $1 trillion for the first time in Canadian history, and Freeland has promised to spend up to another $100 billion in stimulus.

Lee will also be eyeing new big-ticket programs and whether the government will raise taxes.

Indigenous people have good reason to fear budget cuts, and austerity is one way of reducing debt in a hurry. But Lee doesn’t see that happening under Trudeau.

“I do not forecast that they’re going to cut spending for Aboriginal issues,” he says. “If anything, Aboriginal people, especially on reserves, will be seeing announcements of increases in spending under the broad category of infrastructure.”

He predicts the Liberals will work a little financial magic and try to please everyone — or, alternatively, anger as few people as possible — by taking advantage of favourable economic conditions coming out of the pandemic.

The fiscal wizards, he explains, have looked into their crystal balls and predict the economy will come roaring back to life when the pandemic eases.

“They’re forecasting the economy is going to grow five or six per cent,” says Lee. “Those are rates that make the Chinese government blush.”

As huge crowds return to work, they’ll be getting off government-funded income assistance programs. Not only will the cash stop flying out the door, it’ll come rushing back into federal and provincial coffers as tax revenue.

This will naturally decrease the deficit while simultaneously giving Freeland’s department freedom to spend on major initiatives.

“This is going to give Mr. Trudeau and the Liberal government a lot of wiggle room, a lot of degrees of freedom, of fiscal flexibility,” explains Lee, who will be in the lockup Monday.

“The money is going to start gushing in because the economy is going like gangbusters.”

Talk in the capital is that the new big-ticket item could be a national child-care system, and Trudeau has said a tax hike isn’t planned right now.

The Liberals have a slim minority hold on power however, meaning Trudeau needs support of at least one opposition party to pass the budget.

So it could all be moot anyway.

If he doesn’t get the support, the country will head to an election.